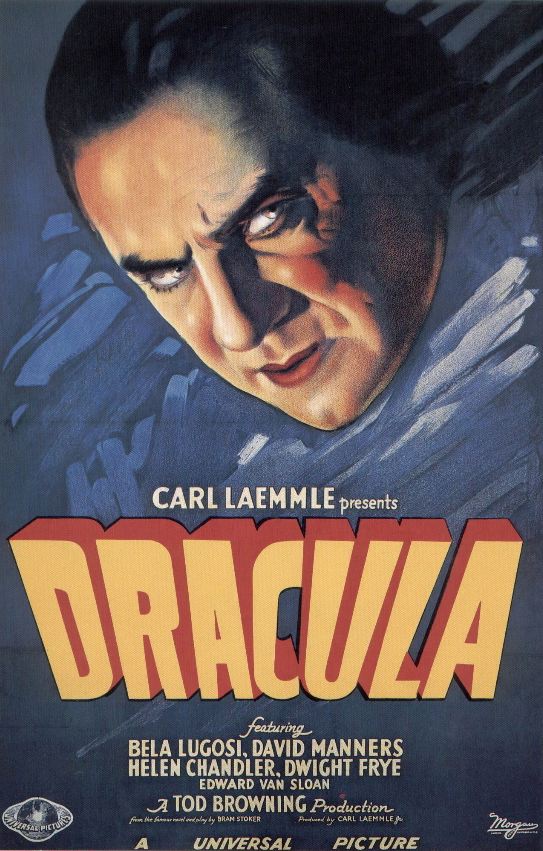

I saw the 1931 version of Dracula so many times as a kid, and listened so

often to a tape of its soundtrack I made off the TV, that at a certain

point I couldn’t see or hear it anymore. Even watching it today I

sometimes find myself speaking the lines before they’re delivered, with

the exact (and always eccentric) vocal inflections of the actors.

I stopped watching it in my late teens, a bit embarrassed by its

clunkiness and lack of sophistication — so it was something of a

revelation to see it again recently in the restored version now out on

DVD and find myself wondrously entertained.

It is a truly demented film, in a way none of the other classic Universal horror films are — and the dementia must be credited largely to Tod Browning, because it echoes the perversity of so many of his silents.

Everyone in the film looks drugged — moves like a sleepwalker or someone in a

woozy erotic reverie. The slow pace can perhaps be attributed in part

to the recent transition to sound — to the need for actors to avoid

stepping on each other’s lines and to the silent-era habit of lingering

on movement for character or narrative exposition that could now be

supplied by the dialogue. But a bigger part I think is a stylistic

choice by Browning — his way of creating an otherworldy and yet

insistently sensual mood.

It’s not quite campy, as James Whale’s style can be — there’s no real wit

to it, no winking at the audience to let them in on the joke. We simply

seem to be watching a film in some unfamiliar Kabuki-like performance

tradition, which demands from its performers a greater degree of

deliberation and a slower pace than we’re used to. The effect is

unsettling but adds to the uncanny atmosphere.

The restored version gives one a chance to appreciate how beautifully the

film is shot — with exquisite lighting and infrequent camera moves

that are nevertheless always effective, either in enlivening an

otherwise static interior scene or in giving the spectator a sense of

being drawn in to a forbidden precinct. The film is so much more

stylish visually than most of Browning’s work that I guess one must

credit the speculation that cameraman Karl Freund was a kind of

co-director on the film — or at least that Browning gave him total

license in creating the look of it.

It has many lapses of continuity, a few of which are really jarring — evidence,

as has been suggested, that someone took the shears to Browning’s

original cut. But when the film slows down in the second half, with its

maddening repetition of expository material in the dialogue, you find

yourself wishing for the shears yourself. The script is simply very

clumsy, and I’m convinced the cutting was done to eliminate unnecessary

dialogue rather than to address any directorial lapses by Browning, who

after all was charged with shooting the script approved by the studio.

The film is never scary, exactly — but it’s creepy, spooky, strange, in

its own unique way. It has a dreamlike quality that allows its

subversive themes to gain sway over the spectator’s unconscious

experience of the film.