As the art critic Dave Hickey has observed, Norman

Rockwell was inspired by the idea of American citizenship, and he often

portrayed the places and occasions in American life which brought

Americans together in that peculiar comradeship unique to functioning

democracies.

In our polarized age, when the gap between rich and

poor grows positively surreal, when urban environments no longer

function as genuine melting pots, when suburban residential patterns

emphasize the isolation of income-brackets, Rockwell's visions of

community take on a nostalgic glow — but in his own time Rockwell was

celebrating something real, something in the now.

I'm particularly fond of Rockwell's paintings of

people on trains — a now uncommon mode of travel in which people from

different backgrounds met as equals, in an environment that allowed for

interaction. There was space and time for interaction — as there

isn't, for example, on an airplane, which has no common space, where

moving about is difficult and hardly encouraged.

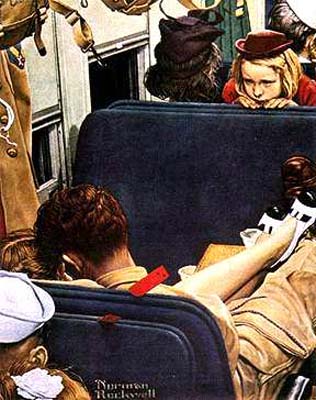

In the painting at the head of this post, democracy rules — a gang of

skiers sets the excited tone of the passenger car . . . the quieter

fellow submits, observes, is perhaps intrigued. He's temporarily out

of sync, but not out of place.

The “Saturday Evening Post” cover below is one of my

favorite images of WWII. A soldier on leave tries to make time with

his girl, while a kid looks on jealously. The soldier, the homefront

and the future intersect momentarily on a crowded train in the middle

of a dreadful war, and we see everything that's at stake in the

conflict.

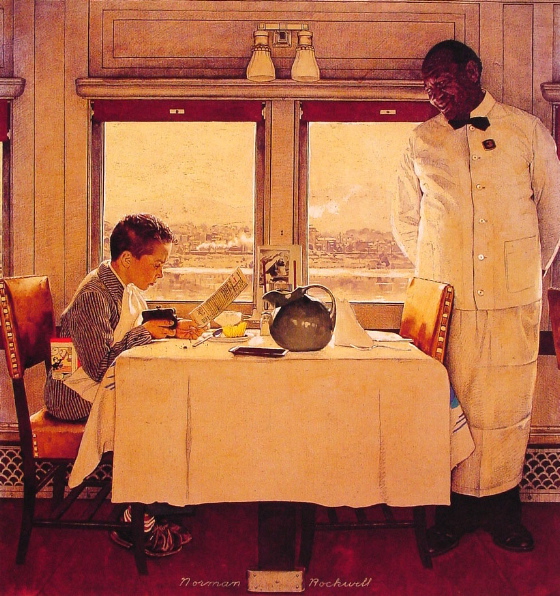

Below, a kid on a train journey by himself is watched

over by a sophisticated professional who's seen it all but still finds

it possible to be amused and touched by the rite of passage he's witnessing,

as the kid tries earnestly to make his way in an adult arena. The

dining car waiter has a job to do — but so does the kid, and he's

working at it.

Americans

of every background meet today as citizens, as equals, only at the polls on

election days, or at casinos — there are fewer and fewer everyday

environments and occasions where one can feel the genuine community of

citizenship, and that's partly why one finds such warm fellow-feeling

at polling places and in casinos. Rockwell was right to be

sentimental

about such places and occasions, and nostalgia is not a sufficient

response to his images of them. They should inspire us to recover

what's been lost.