Mexico has always had a peculiar place in the popular American imagination.

It has generally tended to represent a kind of mirror world where the

subconscious could emerge into the light — where desire, fear, death, despair, escape from responsibility and propriety could show themselves plainly.

There is chauvinism involved here, of course, a sense of Mexico as a

primitive country, but also an appreciation of the positive genius of Mexican

culture, its sensuality, its frank engagement with death and violence,

with things that the official culture of America prefers to keep hidden

in the shadows.

WWII exposed those hidden things for a generation of Americans and in its wake film noir began a systematic investigation of the shadow world at the fringes

(and somehow also at the heart) of American culture. In the

process, Mexico took on a new aura. It became a kind of shimmering

paradise, the locus of an honesty and innocence that no longer seemed

feasible along the mean streets and lost highways of post-WWII America.

So in Out Of the Past, Robert Mitchum and Jane Greer live out a doomed idyll in Mexico, on the run from a gangster who has his hooks into both of them. When they try to carry that idyll north of the border, integrate it into a new life there, they’re both destroyed.

In Border Incident, decent Mexican peasants are exploited and sometimes murdered by powerful American businessmen north of the border who traffic illegally in their labor. (Border Incident, while it deals with a number of themes from classic film noir, departs from the tradition by positing good-guy government agents as saviors of the peasants, thus violating the cosmic cynicism and skepticism of the true film noir.)

In Gun Crazy, the young couple possessed by a mad love, a love fuelled by irrational violence, are just a few hours away from a safe passage over the border when their crimes catch up with them and send them on a final hopeless flight from retribution and death.

The nuttiest use of Mexico in film noir can be found in what may be the nuttiest of all films noirs, His Kind Of Woman. The movie starts off fairly traditionally, with Robert Mitchum as a down-on-his-luck gambler who’s hustled into taking a mysterious job south of the border. As soon as he arrives in Mexico it’s like he’s gone to Oz. He walks into a dingy cantina about the size of a phone booth and in a back room, about half the size of a phone booth, he finds Jane Russell singing Five Little Miles From San Berdoo accompanied by two Mexican musicians doing cool jazz riffs on guitar and piano. Things get so nutty after that that the whole noir genre is pretty much deconstructed by the time it’s all over.

As film noir played itself out in the 50s, the image of Mexico in American art shifted back to a more familiar form. In the Tennessee Williams play The Night Of the Iguana (and in John Huston’s film adaptation of it), in Peckinpah’s Bring Me the Head Of Alfredo Garcia, in Huston’s film of Under the Vocano, Mexico became once more a portal of Hell, where lost American souls went to confront their demons — in an unequal contest which the demons were always fated to win.

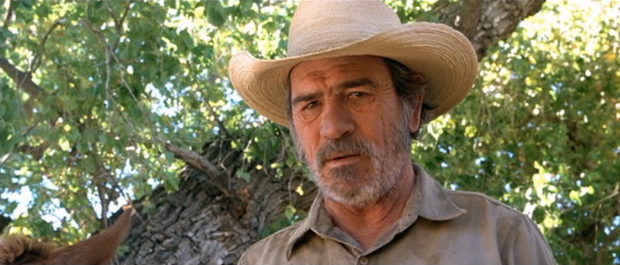

In the light of this peculiar history, it’s interesting to look at a recent film, the post-modern film noir The Three Burials Of Melquiades Estrada. There another troubled American soul heads south of the border on a quest for a lost paradise — only to discover that the paradise wasn’t really lost because it never really existed. And it doesn’t matter. We realize by the end that the quest itself has redeemed and saved him. The film was written by a Mexican, who knows that Mexico is neither Paradise nor Hell . . . except in the dreams of lost souls on both sides of the line.

[For more thoughts on Mexico and film noir go here.]