The first half hour of Herbert Brennon’s Peter Pan is an extraordinary piece of filmmaking, masterful in a delicate and unusual way.

Almost all of it takes place in the Darling nursery, on a set that is shot

from basically one angle and seems designed to suggest a theatrical

stage. I’m guessing that this was a deliberate strategy, meant to

associate the film with the celebrated stage productions of Barrie’s

play, even though it was somewhat anachronistic for a film from 1924. Brennon,

however, has taken this limitation as a challenge, and in his own

subtle way has mastered it.

The long shots of the set, with a frame that seems to mimic a proscenium

arch, are lit with extraordinary care by James Wong Howe. He achieves a

stunning impression of depth in the way his lights define discrete

spaces within the room and sculpt individual figures within those

spaces. Brennon’s choreography of movement within the constricted

location reinforces the stereometric nature of Howe’s lighting.

Slowly, and with great subtlety, Brennon allows his camera to tentatively

explore this space from slightly different angles — almost like a

tease. We never feel that our general sense of watching a stage play is

challenged — but seem suddenly, briefly transported up onto the stage

for a privileged view of the action, as in a dream.

The lighting shifts progressively throughout the sequence in a decidedly

expressionistic way — from the high illumination of the opening to the

more atmospheric shadows of the room lit by the nightlights. Then Peter

appears, and the gears shift radically. Wendy sews Peter’s shadow back

on in a gorgeous half-silhouette downstage, then Peter dances with his

shadow in a circle of light, shot from slightly above, that seems to

have no logical source.

When Peter teaches the Darling children to fly, our head-on view of the set

is explicitly violated as we see one of the boys flying up towards a

camera placed near the ceiling and shooting in a near-reverse angle to

the one we’ve mostly been watching from. It’s a shocking and magical

shift — echoing the shock and magic of the child’s first flight.

Alas, the rest of the film, in Never Land, is not as magical as this first

act. The Catalina locations, the studio forest and underground lair,

the actors in animal costumes and the actors in human costumes never

quite cohere into a vision, despite many delightful passages. The final

action sequence on the pirate ship is confused and dull — until the

wondrously choreographed sword battle between the Lost Boys and the

pirates lifts it all into magic once again.

The special effects vary in quality, too. Most of the wire-work flying is

well done, but the flight of the pirate ship at the end is

underwhelming, and some of the superimpositions involving Tinkerbell

are poorly executed.

This is a title-heavy film, but the titles are faithful to Barrie’s truly

charming text, tastefully selected and arranged.

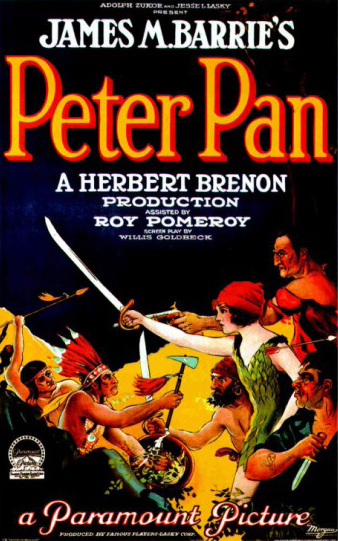

The general result is a very uneven but endlessly fascinating film.

Brennon’s vaguely perverse sensibility, always delivered with a

gossamer touch, is evident most especially in his use and appreciation

of Betty Bronson in the title role. She dances the part in a frankly

sensual way, and she is unmistakably and delightfully female — which

allows Brennon to exploit an unmentionable eroticism in certain

passages.

The half-silhouetted shadow-sewing sequence between Wendy and

Peter has the quality of a sexual encounter, and there is nothing

innocent in the numerous kissing scenes — between Bronson and Mary Brian,

Bronson and Anna Mae Wong, Bronson and Esther Ralston.

When Peter lies down to sleep on the leaf bed after Wendy and the Lost Boys have left the underground lair, Bronson is photographed in a languorous and sensual and purely

feminine pose — which gives Captain Hook’s spying on her a wholly different spin than the narrative might suggest. Hook’s hatred of Peter reads as thwarted lust, pure and simple. He knows as well as we do that the creature on that bed is a woman.

Sex in silent movies was a lot more interesting than it is in movies today.