There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet

an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says,

“Morning, boys. How's the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a

bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

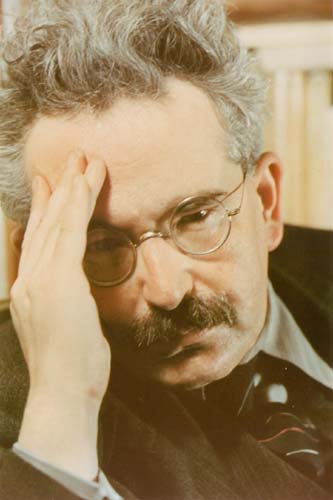

This is an excerpt from a commencement speech given a couple of years ago by the writer David Foster Wallace (above), who committed suicide this week at the age of 46. I don't know Wallace's writing, although it has quite a reputation, but I've been struck by many of the quotes from it that have appeared in various notices of his death.

The quote above is particularly resonant. It reminds me of Walter Benjamin's notion of the “phantasmagoria” associated with each age in history — those dreams that a whole epoch dreams and can't recognize as dreams, because everyone is having them. He's referring to cultural assumptions so profound and so unexamined that they're simply experienced as part of the environment, like water, or air — things noticed only when they're absent. (Curiously, Benjamin, pictured above, also committed suicide, in much different circumstances.)

It seems to me that the principle task of any critic, of art or culture, is to discover the phantasmagoria of his or her time and disenchant people out of it — so it can be seen. It is, as I've written before, a delicate task — like letting a dreaming person know he's dreaming without waking him, because as soon as he awakens, his defenses, his unexamined assumptions about things, will reassert themselves.

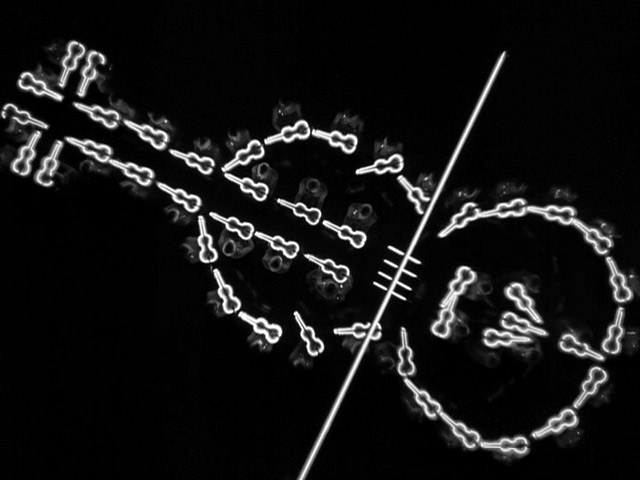

Phantasmagorias exist in the regions of our culture unexamined or devalued by the official, that is to say, the conscious, culture. In the 20th Century, for example, the official culture dreamed that the Victorian Age had been left behind in Modernism's dust, and thus it could not see how the central art form of the age, movies, was essentially Victorian. The official culture dreamed that certain kinds of movies, like musicals, were frivolous and escapist, and thus could not see that they represented some of the century's most radical experiments in cinematic form. The official culture dreamed that Las Vegas was a vulgar cultural aberration, and thus could not see that it was the one place where the 20th Century was anticipating the future of our cities most perceptively (while also, paradoxically, keeping the Victorian tradition of the “universal exposition” alive.)

Image © Paul Kolnik

These observations will seem like clichés a hundred years from now, in retrospect, when we've awakened from our current dreams. It's the job of a cultural critic to get inside our dreams while we're dreaming them.

So how's the water where you are?