Religiosity in 20th-Century art has been a problematic subject for mainstream intellectual critics, unless it could be given a negative twist, treated as a form of neurosis — Hitchcock's “Catholic guilt” being a prime example. This leaves many aspects of many artists' work unexamined.

mardecortesbaja welcomes ventures into problematic subjects and therefore presents without further ado a post about explicit religiosity in the films of Jerry Lewis, written by my friend and fellow film buff P. F. M. Zahl:

Jerry Lewis is often accused of sentimentality, of embarrassing sentimentality, in relation to the films he made in his classic period.

The sentimentality is in massive evidence within The Family Jewels (1965), in which a poor little rich girl who has been orphaned is required to choose her new 'father' from among her eccentric uncles. Lewis plays them all, or over-plays them all. Yet I defy you to not wipe away a tear at the conclusion of the movie, when the nature of her chosen 'father's' sacrificial love comes out. I defy you not to be moved. Even after you have winced through two hours of hammering slapstick.

The God question in Lewis is even more fraught than the question of his sentimentality. I'm not sure that even the French can handle this one.

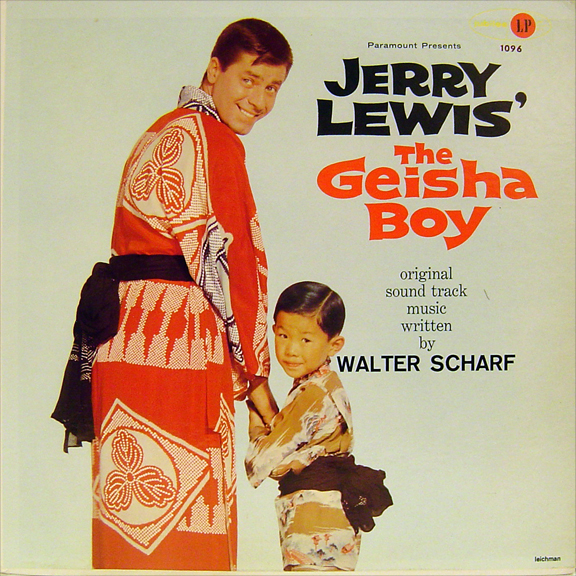

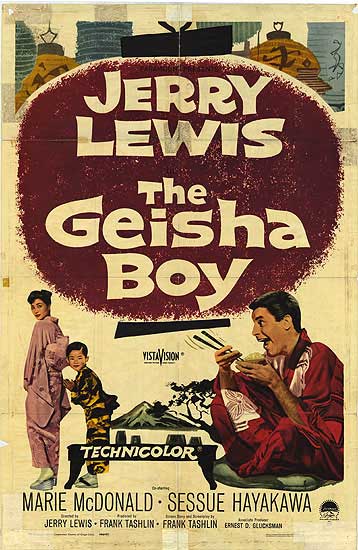

I am thinking of two of the main Jerry Lewis movies that were written and directed by Frank Tashlin. Tashlin, or “Tash”, as Lewis called him, taught his more famous student 'everything I ever learned' about movie-making, and then Jerry took it from there. But to much contemporary sensibility — today, that is — the God factor in two films, The Disorderly Orderly (above, 1964) and The Geisha Boy (1958) is just too hot to handle. And I am not even going to mention Who's Minding the Store? (1963), with its “We're Sorry” denouement written touchingly on the placards that all the lead characters wear as they plead for Jerry to forgive them. Nor will I mention Rock a Bye Baby (1958), with its soaring Grace on the part of the devastatingly unselfish TV repairman (Lewis) who brings up someone else's baby triplets alone.

In The Disorderly Orderly Jerry prays fervently for an old girlfriend, who did once spurn him and continues to spurn him, when she is brought into the emergency room after an almost successful attempt at suicide. Then when she recovers, Jerry prays again — and overdoes it a little — to God, thanking God for answering his prayer. He then proceeds to basically redeem this selfish but also hurt woman, winning her affection in a most 'Christian' manner, if I could put it that way. Every time I show The Disorderly Orderly to a group, the whole place dissolves at the end. And that's almost 50 years after it was made.

To be noted is Frank Tashlin's religion, which he by no means wore on his sleeve and would probably never have referred to. But we also know that “Tash” wrote and directed a short animated film for the Lutheran Church in 1949 entitled The Way of Peace, which is as explicit a Christian warning concerning nuclear war as ever was filmed during that era in Hollywood. This religious short subject had disappeared, and I had the privilege two years ago of bringing it back to the surface from the ELCA (i.e., Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) archives. I believe it can now be YouTubed. In any case, The Way of Peace is an important clue to Frank Tashlin's religious views. [Editor's note: I've written about The Way Of Peace previously, here.]

But it is The Geisha Boy where Jerry and God connect at the most length. Jerry stars as The Great Wooley, a magician on tour with the USO in occupied Japan. He charms a little boy whose parents are both dead and who has not smiled or laughed for five years. Jerry and little Mitsuo connect, and Mitsuo tells Jerry that he is the answer to his prayers. Jerry is moved, comments, and tells Suzanne Pleshette. Jerry then goes to Korea and performs for the GI's, taking time, in a sustained and extremely pointed scene, to pray before an altar — a sort of makeshift battlefield altar — for the little boy back in Japan. Prayer is referred to again, and finally The Great Wooley adopts the boy, takes him (together with his Japanese aunt, whom he marries) back to America, and all three become a happy family magic act. It is not actually all that maudlin.

As someone who believes in prayer, and who sure believes in reconciliation between previously estranged people, I find The Geisha Boy moving and also full of love. Plus, the Technicolor palette is out of sight, from the first shot to the last.

I would even go so far as to 'pair' The Geisha Boy with Kurosawa's Ikiru because they relate to the exact same period in the history of Japan, and in The Geisha Boy the little boy's last name is Watanabe; and as we all know, the hero of Ikiru is named Watanabe. In fact, the 'son' character in Ikiru is named Mitsuo Watanabe and the 'son' character in The Geisha Boy is named Mitsuo Watanabl. You can't convince me that Taslin hadn't seen Ikiru, especially when you hear Kurosawa report that it took them two full weeks to come up with the unusual 'Watanabe' name for the hero of that great classic of world cinema.

Jerry Lewis and God. Jerry Lewis and Frank Tashlin and God. Or maybe it was just the Fifties and early Sixties. But watch for God to appear within the Lewis canon. I also think He's still there, in the telethons. I see God pop up in the telethons all the time. I also know that Lewis, right in the heart of his heyday, treasured above all awards, above all European honors and medals, an award he received from the State of Israel. If you don't think God is friends with Jerry Lewis, then look again. Oh, and note the Buddhist tie-in, too, within The Geisha Boy, in the thumping importance given to the character of Harry the Hare. I don't think that's a coincidence either.

mardecortesbaja would just like to add that it's common, but hardly quite responsible, intellectually speaking, to admire Tashlin and Lewis for their radical dislocations of cinematic convention and their radical critiques of American society and to ignore the spiritual values (or the spiritual sentimentality, if you prefer) which also informs their work. You have ask, was the spiritual dimension an embarrassing aberration in that work, or one of the key sources of its radical attitudes? See my post on The Way Of Peace for further thoughts on this subject, especially as it relates to Tashlin.