[Photo © 2011 Huger Foote]

By a lucky chance I got a look this past weekend at a great work of art in progress — Lisa Giobbi’s Fight or Flight. I have never seen anything quite like it. It combines classically-inflected dance with state-of-the-art aerial effects and the result is breathtaking — technically, but also emotionally.

[Photo © 2011 Huger Foote]

Giobbi (above, second from left with four of her performers from the show, Timothy Harling, Kat Nasti, Julia Wilkins and Shaneca Adams) is a dancer and choreographer who has worked across a broad spectrum of the performing arts, from experimental dance theater to opera ballet to circuses. She is grounded in the language of the fine arts but equally respectful of the noble traditions of popular spectacle. In this age of aesthetic hierarchies and categorical firewalls, she transcends meaningless distinctions between fine art and popular art. There is no fine art or popular art — there is only good art or bad art. “All art is one, man — one!” said Kipling, and any art, high or low, can learn from any other art, high or low. Forgetting this basic truth has impoverished the culture of our time — remembering it accounts in part for the remarkable depth and resonance of Giobbi’s work.

I saw an open rehearsal of excerpts from Fight or Flight at the studio of Flying by Foy, Giobbi’s collaborator on the piece. This is located in an industrial park section of Las Vegas not far from the airport. Flying by Foy specializes in state-of-the-art stage flying technology — providing the flying effects for top shows around the world, from Broadway to The Las Vegas Strip. I had not realized how advanced this technology has become. Lifting a performer on wires into the air on stage is a familiar gag. Today, a performer can be lifted into the air and helped to do extraordinarily complex things while airborne. Partly this advance relies on more and more sophisticated harnesses and rigging, but mostly it relies on the degree to which the operators of the flying equipment have learned to collaborate with the performers at the end of their wires. (Below, Meredith Roat, one of the four operators who performed in Fight or Fight.)

As Dave Hearn, senior operator on Giobbi’s show, says, “We are not puppeteers — we are dancing with the dancers on stage”. Giobbi says that the ropes and wires that connect the dancers to the operators are like bloodlines. One might also see the connection as similar to the connection between a live orchestra playing ballet music and the ballet dancers moving to that music. It doesn’t work unless the connection is also a conversation based on the deepest sympathy and respect, with each side taking the other’s pulse on a moment by moment basis.

Experiencing Giobbi’s show in the Foy work studio one could watch both sides of this conversation at once. Seeing the rigging and the operators did not, curiously, diminish at all the magical impact of the flying dancers. One’s mind could phase from one “reality” to another without disorientation — as it does when watching a performance of Bunraku puppet theater, where the black-clad operators of the puppets are plainly visible behind the magical dolls, putting them through their paces, yet do not take away any of the enchantment of the puppets as illusions of living human beings.

[Photo © Richard Forward]

The crucial difference, as Hearn notes, is that Giobbi’s on-stage performers are not puppets — they are extraordinarily accomplished dancers who by themselves could do what dancers customarily do, make it seem as though the usual rules of gravity do not apply to them. The flying apparatus expands this illusion by several magnitudes, making it seem as though the dancers have cut loose from gravity altogether. It is still illusion — we can see the wires that make it possible — but it remains spookily convincing, in defiance of our rational minds.

Giobbi’s piece at this stage in its development uses two male and three female dancers and four operators. Since it takes two operators to work each flying rig, only two of Giobbi’s dancers could be in the air at any one time. Two of the females appear first, moving close to the ground but not in constant contact with it. They glide and hover above it, sometimes just a few inches above it. The males appear first without harnesses, as though sentenced forever to the ground. They seem tortured, the victims of self-inflicted wounds, eyes often downcast, not even dreaming about the air.

When the two males meet in harness they have been released from absolute gravity, but they stay close to the ground and take the occasion to fight with each other — in a donnybrook that has the quality of a stop-motion fracas from a comic strip. The key actions feel like panels from E. C. Segar’s early, violent Thimble Theater pages, brilliant graphic art featuring the irascible Popeye.

In subsequent passages, the men, out of harness again, dance pas de deux with the hovering women, raising them up, tossing them into the air, holding out their palms to serve as steps leading the women back to the ground again. The women stand on the men’s heads, the men collapse under the weight — not the physical weight, because these women have no physical weight, but the psychological weight . . . of responsibility or, one might say, of commitment. The women console the fallen men, draping their bodies over them but always floating slightly above them.

The men stand up again in an image suggesting resurrection, and the couples waltz, the men partnering with their feet on the ground, turning the women who are — in Jesse Winchester’s phrase, from his song “The Brand New Tennessee Waltz” — “literally dancing on air”. The image of this slightly supernatural waltz suggests a realm where men and women can meet as collaborators, tripping the light fantastic close enough to the earth to accommodate both orientations of the psyche. And of course it suggests the magical nature of dancing itself, even the kind ordinary mortals can perform. It doesn’t last forever, though, as no dance does. The women fly up into the aether and the lights go down. But the ending isn’t a downer, figuratively, any more than it is literally. I thought of Blake’s great lines:

He who binds to himself a joy

Does the wingèd life destroy;

But he who kisses the joy as it flies

Lives in eternity’s sunrise.

[Photo © 2011 Huger Foote]

In Giobbi’s vision, much as in Balanchine’s, the Eternal Feminine is always buoyant, never constrained by gravity, even when touching the earth or flirting with earthbound creatures. The male in this vision is caught in an undertow apparently of his own making — even when given wings he cannot trust them or use them to soar.

[Photo © 2011 Huger Foote]

The simplicity of Giobbi’s vision opens on to profound depths because the exhilarating images of flying connect with the deep impulses associated with flying in dreams, where release from gravity becomes a physical metaphor for the emotional urge for release from psychological bonds. Giobbi’s meditations on the relations between the sexes are thus felt more than understood in an intellectual way — as with dreams, their truths communicate themselves before they can become “observations”, “messages”. Analysis comes later, and can never exhaust the felt meaning of the dream.

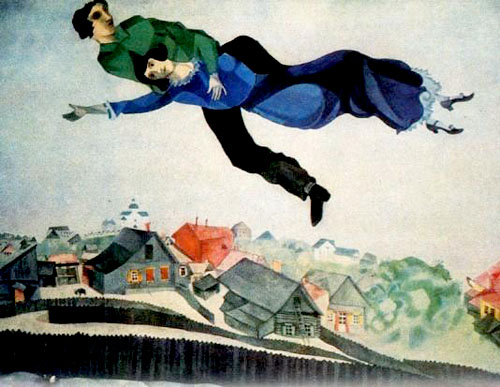

One can appreciate the work on another level as well — as the intersection and synthesis of iconography from other arts. Here, Bouguereau’s insistently solid human forms hovering in mid air (above) find a new equivalent, or echo . . .

. . . as do Chagall’s legendary characters floating above a village.

Esther Williams’s dancing underwater, in which she’s released from gravity by other means than wires, is also suggested. The lyrical, erotic aspect of movement underwater has often attracted performance artists, notably in the shows done at the famous crystal springs of Florida:

Photographer Toni Frissell took a haunting, iconic image at one of those springs for a Harper’s Bazaar fashion shoot in 1947, which precisely evokes certain moments in Fight or Flight:

There is, just by the way, a surprisingly lyrical sub-genre of pornography which records naked people doing naughty things to each other underwater:

Suggested, too, in the imagery of Fight or Flight is Fred Astaire’s dancing up the walls and on the ceiling of a hotel room in the film Royal Wedding. (At one point in Giobbi’s show two of the female dancers, suspended horizontally in the air, “walk” up the sides of the upright men — as startling an image as I know of the conflicting frames of reference that men and women sometimes inhabit, even when they apparently share the same space.)

All these things involve tricks that pretend to overturn the laws of physics, but they result in images so seductive, so resonant of the deep urges of dreams, that we willingly suspend our disbelief in order to participate in the paradigms of emotional instruction and release they offer us. The lyrical and romantic passages inGiobbi’s work look the way sex feels, for example, and are thus more deeply erotic than explicit sexual images can ever be. In explicit erotica we parse the mechanics of sex hoping to recover the emotional, visceral experience of sex. In Giobbi’s unmoored pas de deux, our hearts and our physical imaginings soar directly into the core of the thing — what it’s really all about.