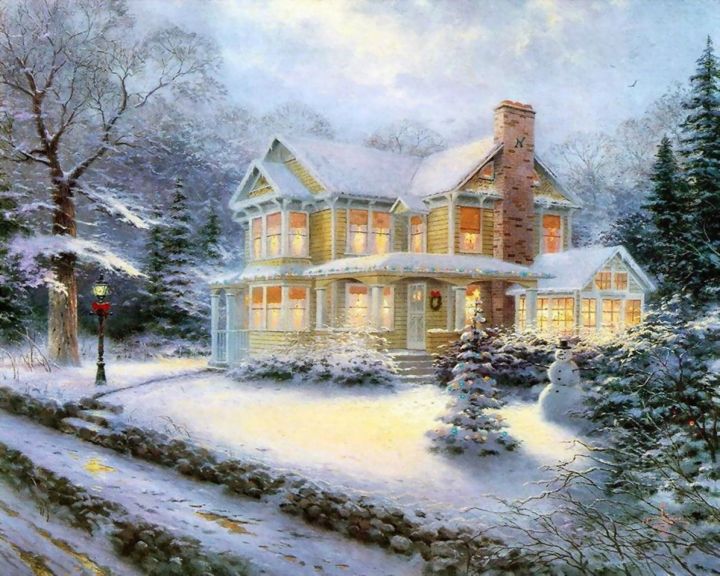

Thomas Kinkade, who painted the image above, died yesterday at the age of 54. It has been claimed that 1 in 20 homes in America has a Kinkade image of one sort or another — a print, or something on a plate or tea towel. Kinkade hawked his work on QVC and commercialized it in every way he could think of.

It has also been claimed that his work is junk, but it’s not junk. Its draftsmanship is serviceable, its painterly qualities are mediocre but professional — good enough to serve his purposes, which are emotional. He called himself — actually trademarked himself as — the “Painter Of Light”, and he used light to summon back the feelings of coziness that a home or a garden can give, with the immediacy those feelings have in childhood.

Kinkade associated light with his Christian faith, using it as a symbol of warmth, welcome and comfort in both his secular and religious paintings. He had a special fondness for Christmas scenes.

Kinkade’s talents and aims were modest, but in the very narrow territory he staked out for himself, he was an artist worthy of respect. His gift reveals itself in that brief twinge of nostalgia, of remembered enchantment, we feel when we first see one of his more successful images — before our critical faculties dismiss it as second-rate, or before it becomes part of the furniture.

I’ve sometimes asked myself whether Kinkade is dismissed for what he is showing as much as for the way in which he is showing it, especially in relation to his religious pictures. They’re sentimental yet at the same time you can’t take your eyes off them — at least for awhile. Also, his “wicket gates”, as shown in this post, are a kind of essence of a Pilgrim’s Progress. They’re inviting but don’t give away secrets about where you’re going.

Recently I found myself in an exhibition of Chinese Communist “realist” paintings of scenes from the life of Mao tse tung and Jo en lai. Several of these pictures moved me, even though they showed only the “glorious” or “humane” aspects of the characters’ lives.

As I looked, a light went on: “Thomas Kinkade”.

In our time, the narrative or emotional aspects of painting have been devalued — relegated to a secondary importance or dismissed as objectionable in themselves. If these aspects are valued, then it’s possible to value Kinkade’s use of them, even if his purely painterly skills are recognized as mediocre, or merely serviceable. To me, Kinkade’s works aren’t deep, they don’t yield up more the more you look at them — they lack the sublime virtuosity of a Rockwell, much less a Rembrandt — but what they yield up at first glance is precious, in its way, not to be sneezed at.

Lloyd, you are pretty decent, interesting guy when you aren’t ranting about how you’re God’s gift to black people.

For some reason, lots of white guys feel compelled to do that.

It’s an awful habit, but I probably have awful habits that I’m not very aware of too.

Happy Easter.

Happy Easter to you, too, Stephen!

my problem with Mr. Kinkade: his work is everywhere. Not that I’m really all that jealous of the jigsaw puzzle franchise or anything. Kinkade’s everywhere and nowhere source of light has become the yardstick used to whack the knuckles of less well-known, but serviceable in their own way painters.

But his light doesn’t just appear promiscuously, to make the image cute — in the image at the head of this post, the light from the windows of the house gilds the puddles on the sidewalk, making them stepping stones on the way into the domestic interior. His light behaves metaphysically.

54 is really young! I’m appreciating that he staked out his territory. Although photography largely absorbed this genre by the time Kincaid was a teen, the more important aspect is that his audience valued his labor in providing these loved ideas for them. They took him personally because by painting and drawing he made them feel like he spent time on them.

Oops. Kinkade.

That’s a good point, Malcolm — the manual craft it takes to paint a picture does have its own sort of commitment built into it. And Kinkade had such precise ideas about how he wanted to portray light that he would have had a hard time duplicating it in a photograph, even in the age of Photoshop. There are a lot of photo-realistic painters who create images like Kinkade’s, but they rarely convey the same impression of warmth.

I’ve often dismissed Kinkade, even among my own family who enjoy his work, but this is a point well taken and a very gracious response. Many thanks for it.

Thanks for taking a look, Matthew, and for leaving a comment — much appreciated.

he really does get the invisible glowing Jesus light. I envy the skill.

It’s a very strange effect.

Pingback: MORE ON THOMAS KINKADE | mardecortésbaja.com

Pingback: Architecture Conundrums: Solvang | Uncouth Reflections