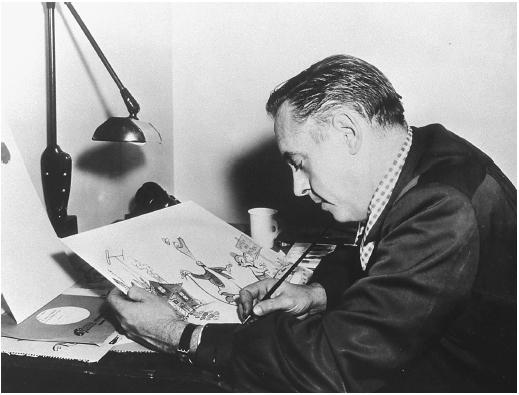

Frank Tashlin was the nut-case genius who unleashed

the nut-case genius of Jerry Lewis as a filmmaker. Before Lewis became

a director, Tashlin directed him in some important movies that helped

set the tone and strategy for Lewis' later work.

Tashlin basically showed Lewis that if in a film you

deconstructed the process of making movies and let the audience in on

the deconstruction in a lighthearted, complicitous way, you could

vastly expand the range of comic eccentricity possible in a mainstream

film. As long as the audience knew you were violating convention

deliberately and “just for laffs” it would then allow you to do and say

almost anything.

Tashlin started out in animation, so he had a good

idea of how much surrealism and aesthetic self-reflexiveness a

mainstream audience would accept. It was his genius to show how this

receptivity could be appealed to in live-action comedy.

The Girl Can't Help It, Tashlin's masterpiece,

starts out in black and white and in Academy ratio. Tom Ewell, the

male star of the film, steps forward towards the camera and announces

directly to the audience that the film they're about to see is in

Cinemascope. He waves his hands and the sides of the image expand to a

Cinemascope ratio. He also announces that the film will be in color —

more prestidigitation and the image becomes saturated with color.

“Sometimes,” he confides to the audience, “you wonder who's minding the

shop.”

Instantly Tashlin establishes a bond with the audience

based on the suggestion that the powers that be in Hollywood would give their customers

less than they wanted if they could get away with it — but Ewell, acting

on the audience's behalf, won't let the industry get away with it. The

implications of this are profound. Hollywood is the establishment,

part of the cultural compact of the nation. Once you're seduced into

suspecting Hollywood, you're ready to suspect everything.

But Tashlin doesn't leave it at that. As Ewell

chatters on, telling us that this movie is going to be about rock and

roll, Tashlin tracks in on a jukebox playing the title song, sung by

the highly suspect cultural icon Little Richard, and the song drowns

out the end of Ewell's monologue. Don't even trust the star, Tashlin

seems to be saying — don't even trust me.

I think it's probably a mistake to parse this film, and

Tashlin's work in general, looking for a programmatic critique of

movies or of American culture. Tashlin, like Nietzsche, is offering a

perspective from which a critique is possible, but he leaves the

conclusions to the viewer. Tashlin was interested in creating a

transgressive frame of mind, a frame of mind in which anything and

everything could be questioned — he wasn't interested in formulating

answers to the questions themselves. He liked, I think, the giddiness

of abandoning, of shattering received forms, the license it gave him to

free-associate — and that's what he does in this film.

The center of The Girl Can't Help It is the

iconic, cartoon-like image of Jayne Mansfield. Somehow Tashlin sensed

that the psychic chaos that could be induced by her sheer carnality was

somehow connected to the energy of rock and roll — that there was a

cultural matrix that generated both. There are times in the film when

he seems to be mocking this matrix, times when he seems to be

celebrating it. In fact he was just observing it in wonder — and

asking the audience to wonder about it, too.

There's a famous scene in which Mansfield bursts into

Ewell's apartment carrying two bottles of milk she's picked up from his

doorstep on her way in. She holds them up to her breasts like

extensions of those already preposterous attributes. On one level it's

a dirty joke. On another level it's a symbol of Mansfield's

innocence. On a deeper level it can be read as an acute analysis of

the male breast-fixation in post-WWII America — not a sexual thing at

all, at bottom, but an infantile regression, a lust for the alma

mater.

There are any number of such suggestive images in The Girl Can't Help It.

The complex ways African-Americans are presented in the film deserve an

essay of their own. One image can serve as an example — the

gorgeous African-American singer Abby Lincoln, dressed in a spectacular

sparkling evening gown, sexy and elegant, is shown on a cabaret stage lit in lurid colors . . .

singing a Gospel song. This is beyond satire, beyond surrealism

— it's an image as strange as American culture itself.

The lines of thought are never clear in Tashlin's best

work — and that's its value. In the

social currents he observed colliding and redirecting each other, echoed in the wildly clashing colors of his cinematography, Tashlin uncovered

perplexing contradictions in America culture and threw them in our

faces like so many custard pies. All we can do in response is wipe the

custard out of our eyes and wait for the next one.

His work in the Fifties was excellent spiritual

preparation for the Sixties — a cultural slapstick routine that still

challenges complacency in any form.