In my last post I wrote:

I would argue that pulp fiction, hardboiled fiction, from the

20s and 30s is something different from the wartime and post-war films that are, to me at least, the heart of the film noir tradition. Film noir

drew on that fiction, just as it drew on the 30s-era crime melodrama

and conventional detective fiction, but it became something new.

So what was new about it?

James Ellroy summed it up best when he observed that the basic message of film noir

is “You're fucked.” It's an existential message, philosophical

(or perhaps theological) in nature. Another way of putting it

might be “The world is fucked, at its core, and there's nothing you can

do about it.” You might temporarily survive the predicament this

puts you in, or it might destroy you, but the predicament isn't going

to change.

This represents a profound divergence from the traditional “hero's

journey”, in which an everyman faces tests and ordeals in the pursuit

of wisdom, of meaning. It also represents a divergence from the

“outlaw ballad” tradition of the 30s-era crime melodrama, in which we

explore the underworld and revel in the transgressive behavior of

society's rebels — all the while confidently expecting the rebel's

death and a reassertion of humane values. In true noir, those traditional values have evaporated.

You have to ask yourself why such a radical divergence from earlier

traditions happened in the post-WWII era, and the answer to me is

obvious. The basic message of war, and particularly of combat, is

“You're fucked.” The soul-shaking experience of hearing this

message delivered in the most brutal terms doesn't go away after the

war ends, even if it ends in victory. It is not subsumed in

feelings of patriotism or in the satisfaction of having done one's duty.

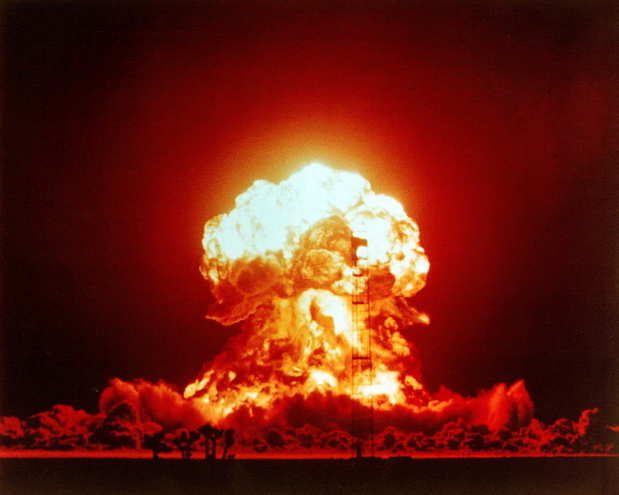

It endures forever. In the case of WWII it had a macabre

objective correlative — the atomic bomb, the image of the mushroom

cloud, which summed up the enduring sense of existential dread that had

infected American society, and in particular its returning war vets.

Film noir was an arena in

which that existential dread could be engaged safely — and there was

something exhilarating about the exercise, the exhilaration of dealing

with an urgent but buried anxiety. The existential dread I'm

speaking of here didn't define post-war America but it was there, and

it couldn't be talked about directly in a world that was desperately

trying to get back to normal. But it could be faced in art — most especially in film noir.

Another great post Lloyd. I agree totally with the “you're fucked” thesis, but I think it's origins are more rooted in European extistentialism through the post-war influence of directors such as Wilder, Siodmak, Lang, De Toth, Sirk, Ulmer, Dmytryk, Tourneur, Von Sternberg et al.

Thanks again for your comment. This is an issue you've reminded me of before, and I haven't forgotten it.

But do we have any direct evidence that these directors were influenced by Existentialism per se while they were still in Europe? I know that Wilder lost family in the Holocaust, and all of these directors would have been keenly aware of the Nazi nightmare in Germany — and that in itself would have created a skeptical view of human society and the human condition.

It wouldn't surprise me if this made Existentialsm attractive to them — but was it a direct influence?

Just a couple of random references on existentialism and noir offered in support of my view:

Robert G. Porfirio’s “No Way Out: Existential Motifs in the Film Noir” (1976) studies the existentialist character of film noir: the anti-hero, existential choice, alienation and loneliness, “man under sentence of death”, meaninglessness and the absurd, chaos and violence, and ritual and order.

Mark Conard looks at Porfirio's definitions and the meaning of Film Noir in The Philosophy of Film Noir:

“This death of God, then—the loss of permanence, a transcendent source of value and meaning, and the resulting disorientation and nihilism—leads to existentialism and its worldview. Porfirio characterizes existentialism as: 'an outlook which begins with a disoriented individual facing a confused world that he cannot accept. It places its emphasis on man’s contingency in a world where there are no transcendental values or moral absolutes, a world devoid of any meaning but the one man himself creates.' As a literary/philosophical phenomenon, set in its particular place in history, existentialism is continental Europe’s reaction to the death of God. My proposal, then, is that noir can also be seen as a sensibility or worldview which results from the death of God, and thus that film noir is a type of American artistic response to, or recognition of, this seismic shift in our understanding of the world. This is why Porfirio is right in pointing out the similarities between the noir sensibility and the existentialist view of life and human existence. Though they are not exactly the same thing, they are both reactions, however explicit and conscious, to the same realization of the loss of value and meaning in our lives.”

There's no question that Existentialism and noir have much in common — I'm just not sure that the former directly influenced the latter. Sartre published a few books in the 30s, but Existentialism as an intellectual movement didn't cohere and become prominent until the 40s and 50s, after the European directors in the noir tradition had immigated to America.

Noir and Existentialism could have been parallel but not directly related responses to the catastrophes of the 20th Century.

In any case it's certainly an area that deserves further study.