Fox home video has been releasing a lot of terrific DVDs in their Fox Film Noir

series — great transfers of entertaining films with generally

excellent commentaries and brief featurettes about the movies and their

creators. They're running out of films from their vaults which

can plausibly be called noir — except that these days, apparently, just about anything can plausibly be called noir.

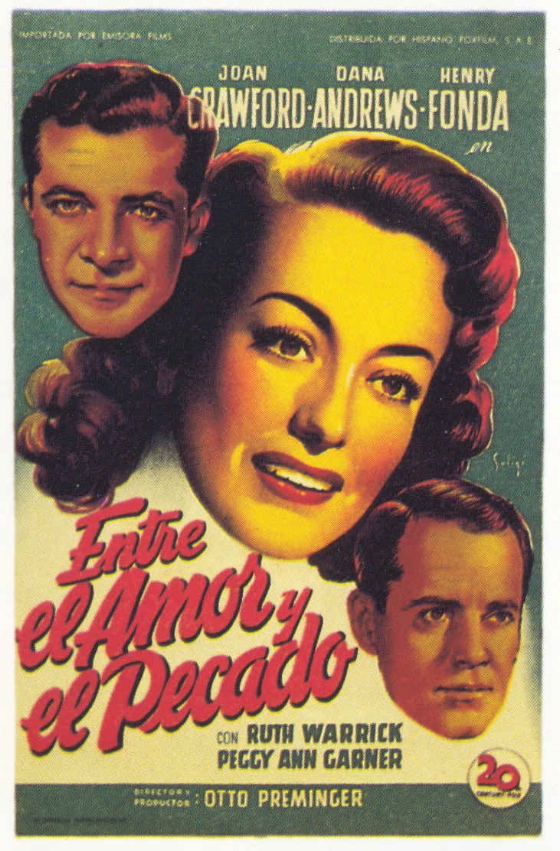

Daisy Kenyon, the 23rd title in

the series, is an extremely interesting film by Otto Preminger from

1947 which could plausibly be called domestic noir,

though it doesn't involve crime or violence in any significant

way. It's basically a soap opera centering on a very complicated

love triangle, but it's disturbingly dark, in ways that wouldn't have been

conceivable in Hollywood before WWII.

Joan Crawford plays a career girl in New York who's having an affair

with a married man, played by Dana Andrews, a charming self-centered

lout. Neither character seems to feel any moral qualms about the

affair, and Preminger presents it with an almost cynical nonchalance

that's strikingly adult and modern.

Crawford meets an equally charming but somewhat unstable returning war

vet, played by Henry Fonda. Fonda's character feels that the

world and everyone in it has become dead, and isn't sure if this

feeling has to do with the loss of his wife in a car accident or with

his experiences in combat. The war, and its collateral moral damage, are also referenced in an off-screen subplot in which

the Andrews character defends a Nisei war vet whose farm was stolen

from him while he was off fighting for his country, heroically, in

Italy. He loses the case.

According to Preminger's biographer Foster Hirsch, these elements

were not prominent in the novel on which the film was based. It

was Preminger and his

screenwriter who chose to associate the moral confusions and neuroses

of the characters with the broader anxieties of post-war American

society, issues of guilt over the price of victory, over the

psychological wounds suffered by the soldiers who won that

victory. It's a theme one finds

in many noir and noir-inflected films of the time, sometimes explored explicitly, as it is here, sometimes only by implication.

Perhaps Preminger was too explicit. Daisy Kenyon

was a box-office disappointment. Without the cover of the

crime-thriller genre, elements of which figure to one degree or another

in most other domestic noirs, the film's investigation of post-war American angst may have cut too close to the bone for contemporary audiences.

The mood of the film is almost unbearably tense and unsettling,

eventually involving child abuse and a scandalous divorce trial played

out in the tabloid press. There had always been soap operas like

this in American movies, of course, but there was always a clear sense

of when moral boundaries were being crossed and what the consequences

would be. Daisy Kenyon plays out in a world in which moral boundaries seem to have been erased.

The Spanish title of the film translates as “between love and sin”

but the tale offers few clues as to where one stops and the other

begins. The romantic triangle is resolved at the end, more or

less, with everyone doing the “right” thing — but there's hardly a

sense of moral triumph. We feel that all the characters are going

to remain adrift in a morally ambiguous universe, trying to walk a line

that none of them can see clearly. This is noir territory, all

right, but strictly domestic, and explored primarily from the point of

view of the female protagonist, which distinguishes it from the classic

noir cycle.