I traveled a thousand miles north to Wyoming this summer, but mardecortesbaja contributor Paul Zahl (see The Zahl File) and his wife Mary ranged even further afield, leading a religious-themed tour to Russia. (Mary and Paul are personable folks, and Dr. Zahl is a widely respected scholar of religion, so they're much in demand for such tours.) Paul was kind enough to send some reports of his adventures, of which this is the first:

EL GRECO IN THE TWILIGHT ZONE

by Paul Zahl

In the movie Russian Ark there is a scene in which an

aristocratic French visitor to The Hermitage Museum at St. Petersburg

lectures a young Russian of the early Nineteenth Century concerning a

painting by El Greco (above.) So moved is the Marquis by this painting that he

kneels in adoration before it. He explains to the young Russian that

the picture bears the image of the founders of Christianity, St. Peter

and St. Paul. The scene in Russian Ark is moving and

beautiful.

aristocratic French visitor to The Hermitage Museum at St. Petersburg

lectures a young Russian of the early Nineteenth Century concerning a

painting by El Greco (above.) So moved is the Marquis by this painting that he

kneels in adoration before it. He explains to the young Russian that

the picture bears the image of the founders of Christianity, St. Peter

and St. Paul. The scene in Russian Ark is moving and

beautiful.

Last month, my wife and I took a group to see the very

painting in person. It is in a room full of El Grecos, but it stands

out for its warmth and the humility of one of the figures. The picture

also tells a story familiar to many: the tension between humility and

grace, represented by El Greco's depiction of St. Peter; and doctrine

and the authority of the truth, represented by St. Paul.

painting in person. It is in a room full of El Grecos, but it stands

out for its warmth and the humility of one of the figures. The picture

also tells a story familiar to many: the tension between humility and

grace, represented by El Greco's depiction of St. Peter; and doctrine

and the authority of the truth, represented by St. Paul.

The picture was painted by El Greco between 1587 and 1592. St.

Peter is on the left, an old and humbled man of soft features and

tenderness. You could approach him and tell him almost anything about

yourself. He is somewhat sad, sympathetic, and modest. The observer

has to look very carefully to notice that Peter is carrying the key to

the kingdom in his left hand. But that is in shadow, almost obscured.

Peter is on the left, an old and humbled man of soft features and

tenderness. You could approach him and tell him almost anything about

yourself. He is somewhat sad, sympathetic, and modest. The observer

has to look very carefully to notice that Peter is carrying the key to

the kingdom in his left hand. But that is in shadow, almost obscured.

St. Paul, on the other hand, while not arrogant, is a person

possessed of his Idea. With his left hand, his left fore-knuckle

actually, he directs our attention to the Word, the Bible before him.

With his right hand, Paul reasons. His features are ascetic,

convinced, sincere, a little detached from persons, but possessed of

his Idea.

possessed of his Idea. With his left hand, his left fore-knuckle

actually, he directs our attention to the Word, the Bible before him.

With his right hand, Paul reasons. His features are ascetic,

convinced, sincere, a little detached from persons, but possessed of

his Idea.

El Greco observes these two great men — I thought of

Rossellini's television movie entitled The Acts of the Apostles (above),

which treats the same men in somewhat the same way — as two sides of

one thing, the Christian faith. There is even a kind of yellow barrier

between them in the painting, emphasizing their difference.

Rossellini's television movie entitled The Acts of the Apostles (above),

which treats the same men in somewhat the same way — as two sides of

one thing, the Christian faith. There is even a kind of yellow barrier

between them in the painting, emphasizing their difference.

My wife immediately noticed the doctrinal character of the St.

Paul, his cerebral, reasoning attitude. It is unmistakable. He is

reasoning with the viewer, on the basis of a written text. St. Peter,

on the other hand, is 'reasoning' with us on the basis of a shattered

wisdom, what Dostoevsky called the 'strongest instrument, the humility

of humbled love'. (I know it is pretentious to quote Dostoevsky, but

his words are apt just the same.)

Paul, his cerebral, reasoning attitude. It is unmistakable. He is

reasoning with the viewer, on the basis of a written text. St. Peter,

on the other hand, is 'reasoning' with us on the basis of a shattered

wisdom, what Dostoevsky called the 'strongest instrument, the humility

of humbled love'. (I know it is pretentious to quote Dostoevsky, but

his words are apt just the same.)

There are few visitors today to this painting by El Greco who do

not identify with Peter at the expense of Paul.

not identify with Peter at the expense of Paul.

But wait, There's something else:

A week later, Mary and I were in the National Gallery of

Stockholm, and there it was (good God!) — the same painting, by the same

artist, in a room also full of El Grecos. But it was different. The

painting had the same subject, composed the same way, with the same

colors, but something was . . . well, wildly different.

Stockholm, and there it was (good God!) — the same painting, by the same

artist, in a room also full of El Grecos. But it was different. The

painting had the same subject, composed the same way, with the same

colors, but something was . . . well, wildly different.

Something had happened to St. Paul. He had lost weight, his

features were pinched, and his hair . . . it was a mess. It was uncombed — what little there was of it was all

over the place.

the old Boris Karloff television series, entitled “The Cheaters”. At

the end of the episode, a selfish man begins to see himself, through

cursed spectacles, as he really is. The makeup artist, Jack Barron,

first shows the man losing his hair and looking himself but bewildered.

Then we see the man grinning diabolically, with hideous scars on his

face and just a few tufts of hair. Finally, we see the man become a

sort of demon from hell, to which he is soon dragged by the very devil

himself. Fun little episode for schoolboys on a Monday night at nine

way back then.

features were pinched, and his hair . . . it was a mess. It was uncombed — what little there was of it was all

over the place.

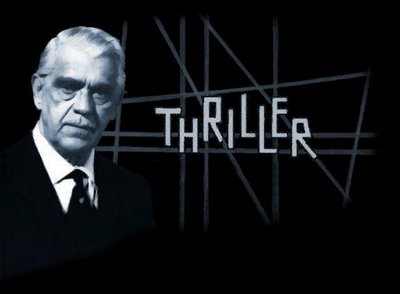

What came to my mind was the episode of

Thriller,the old Boris Karloff television series, entitled “The Cheaters”. At

the end of the episode, a selfish man begins to see himself, through

cursed spectacles, as he really is. The makeup artist, Jack Barron,

first shows the man losing his hair and looking himself but bewildered.

Then we see the man grinning diabolically, with hideous scars on his

face and just a few tufts of hair. Finally, we see the man become a

sort of demon from hell, to which he is soon dragged by the very devil

himself. Fun little episode for schoolboys on a Monday night at nine

way back then.

The comparison seems right, however. What has happened to St.

Paul? His convinced, convicted authority in the Hermitage

version has become transformed into a sort of 'wild man',

'I-just-came-out-of-the-forest-with-Robinson-Crusoe' persona. The

Apostle has entered the Twilight Zone but hasn't come back. Or he is

like the character in a Stephen King story, who is awakened too soon

from a forty-billion-mile journey to a distant planet. Everything's

right but everything's wrong.

Paul? His convinced, convicted authority in the Hermitage

version has become transformed into a sort of 'wild man',

'I-just-came-out-of-the-forest-with-Robinson-Crusoe' persona. The

Apostle has entered the Twilight Zone but hasn't come back. Or he is

like the character in a Stephen King story, who is awakened too soon

from a forty-billion-mile journey to a distant planet. Everything's

right but everything's wrong.

I have looked up the Stockholm version of “St. Peter and St.

Paul” and found nothing on this weird difference. I can't believe it

has gone unnoticed. But it is disturbing.

Paul” and found nothing on this weird difference. I can't believe it

has gone unnoticed. But it is disturbing.

A final thought on El Greco's two St. Pauls. The kind of

doctrinal Christianity embodied by the Hermitage Paul, text-weighted

and cerebral, is superannuated. You see it today and you run. The

painter seems to have understood this instinctively. His later St.

Paul has sort of gone crazy. “Grandfather, we need to get you to the

hospital.” This Paul is not Diogenes, an old man of self-contained

de-constructing wisdom. He is a street-crazy — maybe inspired, like the

homeless man in Ordet, who has faith enough to raise the dead,

but you wouldn't take your child to him for a blessing.

benign at all.

doctrinal Christianity embodied by the Hermitage Paul, text-weighted

and cerebral, is superannuated. You see it today and you run. The

painter seems to have understood this instinctively. His later St.

Paul has sort of gone crazy. “Grandfather, we need to get you to the

hospital.” This Paul is not Diogenes, an old man of self-contained

de-constructing wisdom. He is a street-crazy — maybe inspired, like the

homeless man in Ordet, who has faith enough to raise the dead,

but you wouldn't take your child to him for a blessing.

Or, maybe he

is “The Howling Man”, of

benign at all.

I don't know which of these two possibilities is the Stockholm

St. Paul. But if the Stockholm Paul is the confessional Protestant of the two,

St. Peter is looking pretty good by comparison. And wasn't Senator Kennedy a good

advertisement for that side of the enterprise? [Editor's Note: Paul has elaborated Mary's insight about the portrait of St. Paul into a very provocative meditation. St. Paul wrote some of the greatest and most radical spiritual treatises of

all time, and they were a cry from the heart against law as a spiritual tool — but what he wrote was still theology, and all theology seems to have a

tendency to decompose into law, to be parsed for “rules” which can be

used to oppress instead of bless. A spooky thought occurred to me while reading Paul Zahl's piece — maybe the Stockholm portrait of St. Paul was once an exact copy of the

one in the Hermitage and has decomposed over time, like the portrait of

Dorian Gray, reflecting the historical misuse of St. Paul's letters. The

Twilight Zone, indeed!]

St. Paul. But if the Stockholm Paul is the confessional Protestant of the two,

St. Peter is looking pretty good by comparison. And wasn't Senator Kennedy a good

advertisement for that side of the enterprise? [Editor's Note: Paul has elaborated Mary's insight about the portrait of St. Paul into a very provocative meditation. St. Paul wrote some of the greatest and most radical spiritual treatises of

all time, and they were a cry from the heart against law as a spiritual tool — but what he wrote was still theology, and all theology seems to have a

tendency to decompose into law, to be parsed for “rules” which can be

used to oppress instead of bless. A spooky thought occurred to me while reading Paul Zahl's piece — maybe the Stockholm portrait of St. Paul was once an exact copy of the

one in the Hermitage and has decomposed over time, like the portrait of

Dorian Gray, reflecting the historical misuse of St. Paul's letters. The

Twilight Zone, indeed!]