It’s hard to imagine that there will ever be another movie like 1900. The sheer size of its physical production (as opposed to the CGI resources it deploys) and the care and imagination

lavished on almost every scene, every set-up, every shot, seem beyond the resources and the ambitions of modern filmmakers.

When it came out, in 1977, Pauline Kael said it made every other movie released that year look like “something on the end of a toothpick”. It makes most movies ever released look that small.

Which is not to say that it’s a grandly satisfying film, that it doesn’t fail on many levels — but it really is a hell of thing to look at and experience.

Bertolucci’s initial cut of the film clocked in at something over five hours — and that’s the only length at which the film makes sense. There’s no urgent narrative at the heart of it that

emerges when it’s pared down — abridgment just violates the leisurely pace of the film, which asks us to immerse ourselves in images, in recreated eras, in the slow meandering of history.

If you can surrender to its pace, relish its imagery without hurry or anticipation, you are treated to an orgy of cinematic beauty — a pure and joyous celebration of the possibilities of the medium.

You can forget, or set aside, what’s wrong with the film — its programmatic characters, who sometimes come to dramatic life but just as often stayed fixed in their roles as

political archetypes, its naive celebration of the romance of Communism, its cartoonish reduction of history into icons and slogans.

What you will remember are places, times of day, the play of light, the choreography of peasant dances and cavalry charges and duck hunting from small boats.

Afterwards you’ll find yourself wishing the film had been better — but while you’re inside its rapturous, disjointed visions, it’s hard to imagine anyplace you’d rather be.

[A DVD with Bertolucci’s original cut, in an excellent transfer on two discs, has just been released, and it’s well worth owning — it may be the only five-hour-plus film you’ll want to look at again and again.]

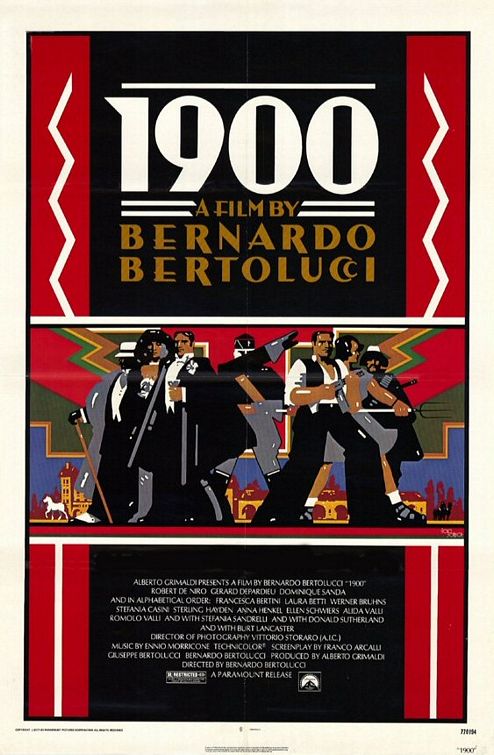

The picture above — showing Bertolucci, in the checked cap, setting up a shot on 1900 — is from a web log that regularly posts great images from film and popular culture. Check it out here:

If Charlie Parker Was a Gunslinger, There’d Be a Whole Lot of Dead Copycats