As art forms go, the silent feature evolved with lightning speed. Barely two decades passed between the commercial inauguration of film as a peepshow attraction and the magisterial eloquence of The Birth Of A Nation. Less than fifteen years after that the silent feature was gone, apart from what Donald Crafton has called the pyrrhic victory of

Chaplin’s sound-era silents.

The speed of its evolution and the brief span of its dominance meant that it was always a medium in transition. One of the excitements, and sometimes one of the frustrations, of watching silent films is the frequent collision of artistic strategies within a single work. He Who Gets Slapped is a perfect illustration of the phenomenon.

First, you have the play on which it is based — an apparently serious lyric tragedy of the sort that would have perhaps struck readers of the old Saturday Evening Post as highbrow. Derived from this you have the film scenario itself, a wonderfully preposterous and unapologetic piece of Grand Guignol, in the best Theater of Blood tradition. And then you have director Victor Seastrom’s treatment of this scenario, an exaggerated and stylized but basically straightforward narrative presentation of the Grand Guignol element, interspersed with metaphorical visual interludes designed to remind us of the work’s

original pretensions.

Finally, at the center of it all, unifying if not quite synthesizing the disparate elements, you have the very great plastic art of Lon Chaney, supported by several other players — Norma Shearer, John Gilbert and Tully Marshall in particular — who can inhabit the world of Chaney’s eloquent pantomime.

It’s the power and force, the unprecedented aesthetic phenomenon, of a great

silent film actor like Chaney which by its nature confounds the conventional artistic strategies of the piece. The flowery poetic intertitles, which I suspect derive from the play, and the interpolated visual metaphors, are so inferior to Chaney’s performance that they stop the narrative dead. They seem to be apologizing for the sensational nature of the story, the outrageousness of the purely narrative images.

But the purely narrative images are astonishing and fine, pushing an apparent naturalism just a little too far — into the demented dreamscape of the story itself. The odd, mournful swaying of the clowns’ dance, the fantastic dappled sunlight of the Gilbert-Shearer picnic, even the obviously faked inserts of Gilbert and Shearer “riding” the horse, achieve a perfect balance between plastic beauty and a coherent representation of a convincing screen place.

There have been other arts which, in times of rapid transition, displayed this same sort of aesthetic discombobulation. Titus Andronicus, for example, mixes the brutal, grotesque vision of Marlowe with the more ambiguous and humane treatment of character with which Shakespeare would eventually modify Marlowe’s great innovations in theatrical form.

But not yet having internalized Marlowe’s lessons, Shakespeare simply apes Marlowe’s shock tactics and tries to present them in his own voice. The result is disconcerting and perpetually strange.

Seastrom’s arty gloss on the great cinematic achievement that lies at the core of He Who Gets Slapped has the same flavor of insecurity — of lessons not yet internalized, of forces not yet appreciated. John Huston once told James Agee that film can’t be used metaphorically, since filmed reality is by its nature already a metaphor. There is something in Lon Chaney’s eyes, in the way he moves under that clown make-up and clown costume, which is beyond the range of literary expression, beyond the range of metaphor. “He” is a dream image — and dreams always get diminished by conscious interpretation.

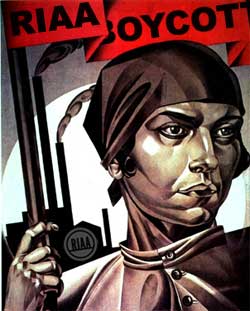

[Above is the principal cast and crew of He Who Gets Slapped — that’s Seastrom in the vest and bow tie standing between Shearer and Gilbert.]