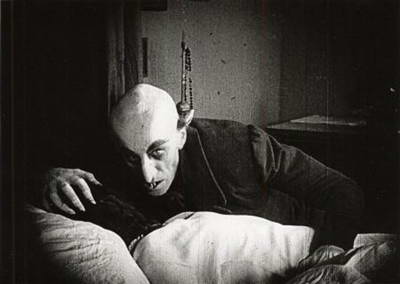

Max Schreck’s Count Orlock shares a distinction with Lon Chaney’s Phantom,

Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Rudolph Valentino — he’s an icon

from the silent era that’s still alive in the popular imagination. Kids

who couldn’t tell you the difference between John Barrymore and Lillian

Gish know Nosferatu.

Partly this is because Orlock is such a powerful icon, visually, and partly

it’s because anyone who has ever seen even the shortest clip of the

vampire in “Nosferatu” simply cannot forget it, so powerfully is Orlock

presented cinematically in the film. Orlock is the heart and soul of

the film — the part of it that inspired Murnau’s genius. Scenes

without him can be visually conventional, and the storytelling in

general can be clunky. (Murnau was still feeling his way as a

storyteller in 1922.)

The acting is very exaggerated, which suits the tale, but runs the usual

risk of highly stylized performance — if it isn’t executed brilliantly

it can seem silly. (But that’s the thrill of it, too — it’s the

thespian equivalent of trapeze flying without a net.) The young

protagonists of the tale are not terribly skillful here, and don’t seem

to have interested Murnau very much, so their expressions of marital

bliss, and later angst, can seem unconvincing, even icky. The actor who

plays Knock, however, a borderline nut-case who travels a long way

across that border in the course of the film, is sublime — he’s like a

genuinely insane person imitating a silent film actor and the result is

thrilling, funny and ghastly all at once.

The only featured player who doesn’t go over the top in the film is Max

Schreck. He moves in an exaggerated (sometimes supernatural) way, of

course, but it all seems organic — this is just Nosferatu, an

admittedly strange creature, being natural, being himself. He never

leers or threatens or grimaces — he just kills, like the Venus flytrap

or the carnivorous polyp he’s compared to visually in the film. And

there is a softness in his eyes suggesting loneliness, even shame —

qualities which Klaus Kinski exaggerated pointedly and too crudely in

Herzog’s remake of the film, to engage our sympathy. But Schreck’s

inhuman humanness wouldn’t be affecting, wouldn’t be terrifying, if he

used it to appeal to us. He’d just be a character, an actor in some

great make-up. It’s no wonder people have imagined that Schreck was a

real vampire — that’s how great and subtle his performance is.

Nosferatu incarnates the poetry of death, its cool, elegant efficiency and power,

which has a kind of awesome beauty. His face is the face we most fear

— an image of anyone, of ourselves, as a corpse — yet can’t resist

looking at. It is Murnau’s genius, and Schreck’s instinct or craft,

which let us experience the deep fascination of that face and remind us

of its familiarity. It’s one we will all have someday — and perhaps

that is why a little part of the human heart goes out to Nosferatu.