The spooky, wonderful image above, Duel After A Masked Ball, was painted by Jean-Léon Gérôme, one of the great masters of Victorian academic art. To me, his work aspires to the condition of cinema and can be studied in that regard with great profit. I think one finds in it, both formally and in terms of subject matter, the reflection of many concerns that would help shape the emerging art of movies.

Gérôme used a photo-authoritative style to make his visions of Oriental scenes and his recreations of historical periods alive and true to viewers who were beginning to process the visual world more and more through the medium of photography. He was concerned with narrative images and used the illusion of depth to draw the viewer into those images — the drama of space obsessed him. He was so concerned with stereometric forms that he also worked regularly

as a sculptor.

Though he died in 1904, before movies came into their own as a plastic and narrative medium, he would have thrilled, I think, at their capacity to carry his aesthetic methods into new realms and elaborate them fantastically.

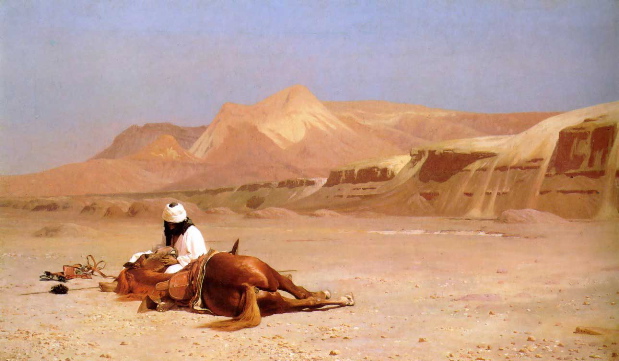

Gérôme‘s Technicolor über-photographs can seem like frame-grabs from imaginary movies. You can see the compositional style of Lawrence Of Arabia (and John Ford) in his desert scenes . . .

. . . foreshadowings of Intolerance in his 18th-Century tableaux . . .

. . . the epic visions of De Mille in his Biblical scenes . . .

Griffith, De Mille and Ford would have been familiar with Gérôme directly — his work was wildly popular and widely reproduced in the time of their youth. Lean may have echoed Gérôme simply by sharing his formal concerns, though it wouldn’t surprise me at all if Lean knew and admired his paintings. In any case, the profound connection between Victorian academic art and the cinema is nowhere more evident than in the work of this great painter.

To me, the image below of Pygmalion’s sculpture Galatea coming to life can serve as a metaphor for the advent of movies, when the aesthetic aspirations of the Victorian academic painter came into fuller life through motion itself.

I actually think Gerome is more in the category you've been interpreting for Victorian artists in this way… what Gerome was great at was creating theatrical images, but his images tended not to be really particular uses of the medium. When he created sculptures he often made them ultra-realistic and painted them, so that being in the presence of one would feel like being in the presence of a frozen person. When he made paintings he sacrificed painterly value to theater and could look garish. But to other artists of the time, including Bouguereau, the tradition of how to use the medium was just as important and everything was idealized fit the aesthetic. If you look at a sculptor equivalent of Bouguereau, I would say Louis-Ernest Barrias, the difference with Gerome stands out.

Gerome was the subject of some recent exhibition at the Dahesh Museum which argued his important relationship with his art dealer, and that Gerome, in a way unique to him compared to other artists of the time, basically created paintings to be reproduced and sold everywhere, that he understood art as production decades before Warhol.

In a sense, I think Gerome's style becomes more natural to film, although when film creates images like that they're also momentary images in the movie based on some dramatic moment that seem modeled on paintings. Bouguereau's style I think is a different thing, I think its more natural for painting, though it shares certain modeling qualities similar to film images, I don't think they could be gotten away with in film, it wouldn't work at all. Besides all of the other reasons which I think are obvious (inlcuding that it would feel absurd in a film to stage a Birth of Venus), I want to underline that I think his paintings rely on generalized forms that actors couldn't replicate, and an exacting use of colors and composition that would also be hard to replicate in the course of a film. There's also a certain 'flatness' that it depends on.

Part of the reason though that Gerome's art feels so much like it could be film imagery though is that artists in France and Europe generally regularly visited the theater and did studies from actors there, watching their expressions, and gaining inspiration. Sarah Bernhardt was a constant source of inspiration for artists. A lot of the more theatrical expressions in Bouguereau paintings are based on observations of actresses who performed. The importance of theater in the 19th century is a very little realized thing. Aside from a (relatively) well known figure like Bernardt, a lot of other actresses were household names. But Academic artists (which most of these Victorian artists are called) also just brought a lot more attention to the human form and the ability for it to express an emotion or subject, so their canvases focused on human sentiment more strongly. There was a competition in France where artists had to best capture an idea or emotion or expression in human form.

A lot of subjects for paintings were also popular and you'll see paintings on the same theme with the same title by many artists. Here is The Duel after the Masked Ball, by Thomas Couture, who I think more worked within painterly aesthetics than Gerome:

http://www.artrenewal.org/asp/database/image.asp?id=14043

Yes, the Couture is much more painterly, but you make a good point about the shared dramatic themes and subjects of the academic painters. These migrated very naturally into the early cinema, which was able to elaborate them in more complex ways. Because the intellectuals who supported modernism insisted on seeing cinema as a “new” art form, much of what wasn't new about it at all has been submerged. The development of cinema has been seen as a breaking away from Victorian theater, but it was also an extension of many concerns that informed Victorian academic painting, which included but weren't limited to the theatrical sphere. It's a subject crying out for deeper study.

Pingback: Listing Books: Anti-Modernism | Uncouth Reflections