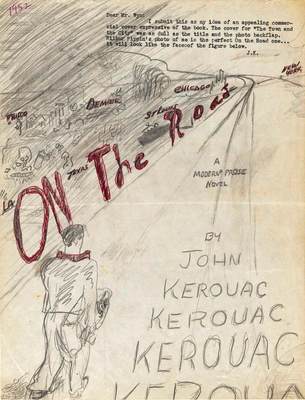

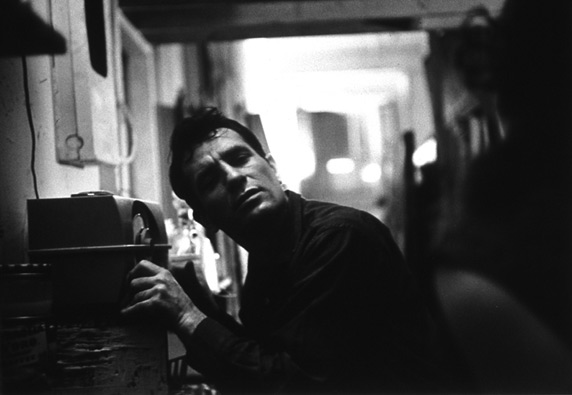

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of Jack Kerouac's On the Road

and the book is getting a lot of attention. (That's Kerouac's

design for the book's cover above.) It was certainly an important

book — crystalizing the odd malaise that gripped America after WWII

and presenting an image of the way American youth would react to it, in

increasing numbers, by cutting loose from everything, drifting into a

world of sensuality and drugs, hitting the road in search of . . .

something. The book's freewheeling, lyrical prose was brilliant

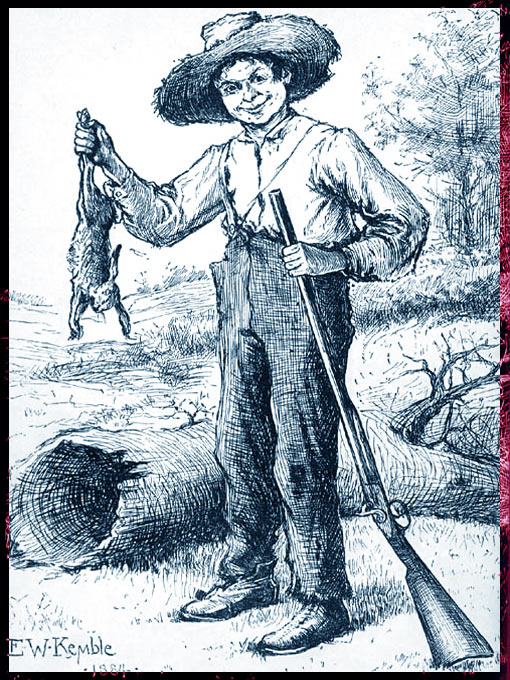

enough to allow one to take it seriously as a work of art, to place it

in the picaresque tradition of Huckleberry Finn.

The moral and spiritual emptiness of On the Road's

protagonists was part of the

book's truth, of course, but that truth, to me, was a thin one, without

any deep humane dimensions — and this is nowhere better revealed than

in

the book's depiction of women. It's not just that Kerouac's

protagonist's treat them badly, or indifferently, but that they don't

seem to see them as human beings — and, more importantly, that the

author himself doesn't seem to see them as human beings. This is

quite a different thing from writing women characters badly,

unconvincingly — quite a different thing from ignoring women or even

raging against them for their otherness, as Henry Miller sometimes

did.

Kerouac simply seems to see women as an existential nullity.

Some women say this doesn't bother them — that the freedom

and exhilaration of the book's spirit is an inspiration to them as

women, however the women in the book are drawn. I can appreciate

the sense of that — but it doesn't lessen my revulsion at the way the

women in the book are drawn. It strikes me as revealing a basic

truth about almost all beat fiction and poetry — that once you get

past the attitude, the style, there's very little underneath it, and

what there is underneath it is often repellent.

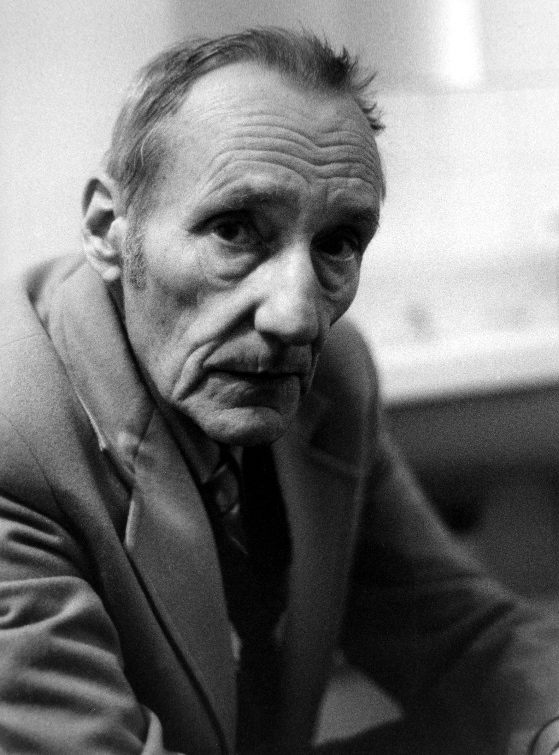

William Burrough's magical, fractured prose, best appreciated in his

recorded readings of it, is invigorating and exciting — but a little

of it goes a long way. It's like a jazz improvisation on a melody

that the musician has forgotten, or never knew in the first

place. It's a gesture, an exercise, not an artistic creation.

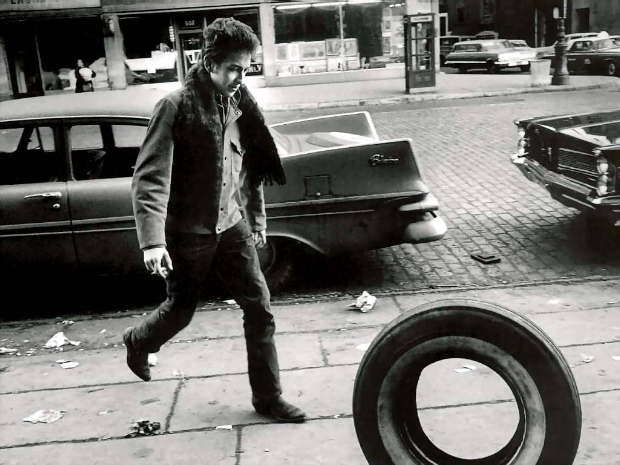

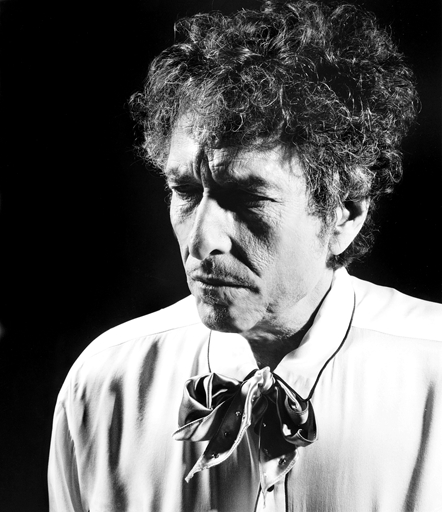

Bob Dylan was the great inheritor of the beat tradition, but he

grounded his improvisations firmly in the blues and folk traditions —

he was engaged, with a great deal of humility, in a conversation with something beyond himself.

His early work is marred by some of the same misogyny one finds in the

beats, by images of women that alternate between goddess and destroyer,

with no convincing human presence in either.

But Dylan, unlike the beats, grew as an artist. He listened to

the culture around him, its roots and moods, and talked back to

it. His work wasn't just an interior howl, a negation — he was a

rolling stone who could step outside of himself and watch himself roll.

When Kerouac tried that he was appalled by what he saw — or didn't

see. He ended his life drunk, stoned, in a state of utter decay and

despair. We can see the roots of that in On the Road. Kierkegaard said that the precise quality of despair is that it is unaware of itself. On the Road

is a harrowing portrait of a despair that is unaware of itself — one

its author shared, unawares, with the book's protagonists.

Kerouac's defenders say that only the work matters — not the

life. But I say that with Kerouac the life is in the work — is

not

transcended in the work. Which is not to say that the book isn't an

extraordinary thing, with passages of true greatness, depictions of

places and moods that are indelible, an authentic and often moving

voice with it's its own kind of feckless grandeur. It's just to say that there's something missing from it —

some element of heart and soul and sympathy that is crucial to any great work of art.