In 1963 Jean-Luc Godard published in Cahiers du Cinéma his list of the top ten American sound films of all time.

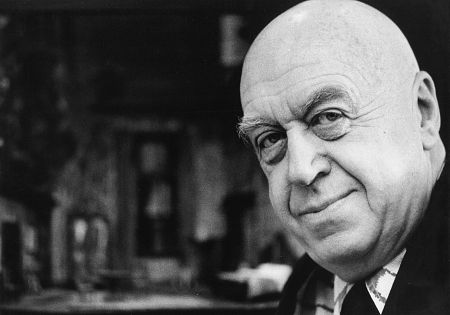

It featured many of the usual suspects — Vertigo, The Searchers — and one film you'd never expect, at least not these days . . . Angel Face (above), a classic film noir directed by Otto Preminger.

Among the French New Wave directors, Preminger was considered one of the

masters of cinema, who could be spoken of in the same breath with

Welles or Ford. Today he holds a place somewhere between Cecil B.

DeMille and Fred Zinneman — considered a first-rate showman, as an

incarnation of the directorial persona, but otherwise a merely

competent craftsman of studio product.

I really can't explain what happened to his reputation as an

artist. Perhaps the theatricality and commercial calculation of

his directorial persona cheapened him, made him seem less than serious,

as it did for DeMille and even Hitchcock for many years. Truffaut

made Hitchcock respectable again, and DeMille seems to be undergoing

reevaluation these days. Preminger is admired, if he's thought of at all, for his early noirs, and for the noirish Laura. The major works of his later years are appreciated somewhat less enthusiastically.

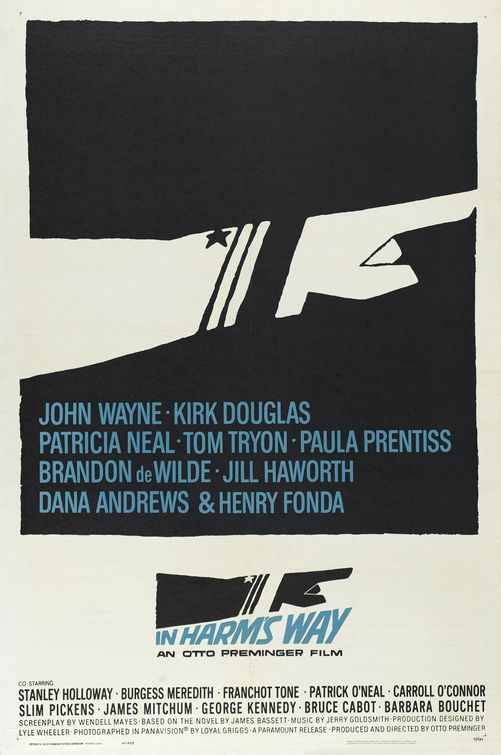

These later films, like In Harm's Way,

for example, have the feel of standard studio prestige pictures of

their time — but in truth they're far more interesting than that,

certainly on a visual, cinematic level. They are

filled with movies within movies — elaborately choreographed scenes

that often play out in one or two shots with a highly mobile

camera. These passages are breathtaking — they impart a sense of

being someplace rather than of watching something.

They are, as the New Wave critics might have put it, passages of pure

cinema — examples of the discursive style largely lost to mainstream

movies since the coming of sound. Ford, also working in the

mainstream, got away with this sort of thing mostly because he worked

in genre — in Westerns we were supposed to sit back and enjoy watching

men ride horses through spectacular spaces. But the long tracking

shot that contains almost the whole first scene of In Harm's Way,

set at a naval officers' party in Hawaii on the eve of Pearl Harbor, is

very unusual in a big-budget studio melodrama. It's exceptionally

effective — drawing us into the time and place on a subliminal level,

making us feel vulnerable to the Japanese attack that's unleashed the

next morning.

Almost all of Preminger's films have passages like this and they linger

in the mind, even if the film as a whole is disappointing. Bonjour Tristesse

is one of the most disappointing of Preminger's films, but its mood and

sense of place were the things Godard riffed on to produce Contempt

— which is almost a formal variation on the visual and dramatic themes of the

earlier work. (And of course it was Jean Seberg's odd but

compelling performance in Bonjour Tristesse that inspired Godard to cast her in Breathless.)

Preminger is due, overdue, for a comprehensive critical reevaluation.

Hi Lloyd

A new biography of Mr Preminger has been just been published, with an auteur focus. See:

http://www.metroactive.com/metro/11.28.07/books-otto-0748.html

http://movies.nytimes.com/2007/11/11/books/review/Schickel-t.html

Thanks for the heads up on this — it looks like an interesting biography and I'm looking forward to reading it!