This living hand, now warm and capable

Of earnest grasping, would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights

That thou wouldst wish thine own heart dry of blood

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calmed—see here it is—

I hold it towards you.

This poem was not published during Keats's lifetime. It was found after his death, written or copied on the manuscript of another poem. The last line is startling, as though the poet were trying to reach out from the page, emphasized by the shift from the expected “thee” to “you” in the last line. In Keats's day “thee” was considered the loftier usage, more fitting for a poetic utterance — “you” brings the poem into the world of vernacular speech, like the hand trying to reach out into the reader's reality. Keats holds his hand out not to thee, gentle reader of poetry, but to you — you, whoever you are.

Since this was one of the last poems Keats wrote, when he knew he was dying, we can read the reaching out as something directed at us, at posterity, from the grave he knew he would soon inhabit. Perhaps it also embodies a cry of despair about the limits of poetry itself. On a more literal level it may have been addressed to Fanny Brawne, his muse, from whom he knew he would soon be parting.

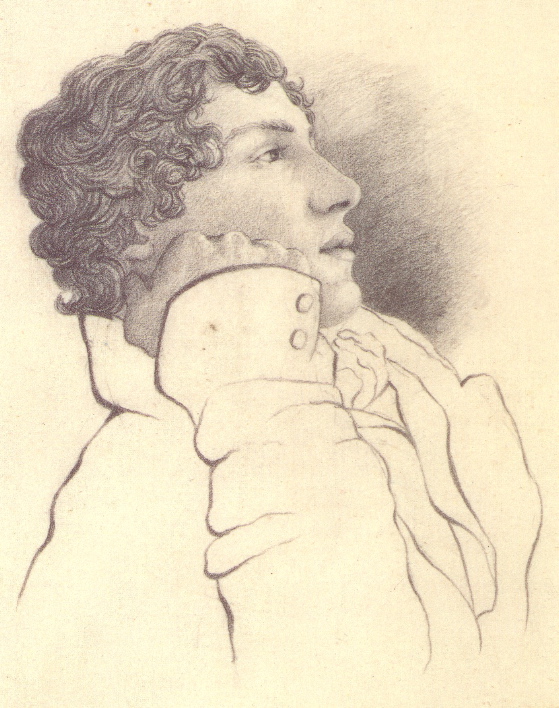

The sketch of Keats above is by Charles Brown, made in 1819. Within two years the beautiful boy it records would be dead of consumption at the age of 25, in Rome, where he had traveled in hopes of a miracle cure. A letter from Brawne which reached him after his death was buried with him, unopened. At his request these words were carved on his headstone — “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.” Within the long shadow of Eternity, all our names are writ in water, but the brook where Keats's name is writ still sings, and will probably continue to do so for quite some time.