Ivan Shreve over at the ever wise and amusing Thrilling Days Of Yesteryear writes, “The argument over whether or not Boomerang! is a legitimate film noir will rage on until eternity.” Of course it will. Arguments about what films are or are not noir are almost always irrational and thus can never be settled in any reasonable way.

The general idea is to parse any film made in Hollywood in the 1940s and 1950s searching for reasons to call it noir. The use of shadows, the element of crime in the plot, any suggestion of moral ambiguity or darkness in the characters is usually enough to qualify a film for the designation. The truth is that film noir is no longer a descriptive or analytic term but one of approbation — it means “a film which is cool, a film I like”. Sometimes it just means an old film in black-and-white which isn't a comedy or musical.

It would be far more logical to ask a simple question up front — is there some other established genre or tradition into which a particular film fits? If there is, there's no conceivable reason to tag it as a noir. Doing that just makes film noir a term so vague as to have no real meaning at all.

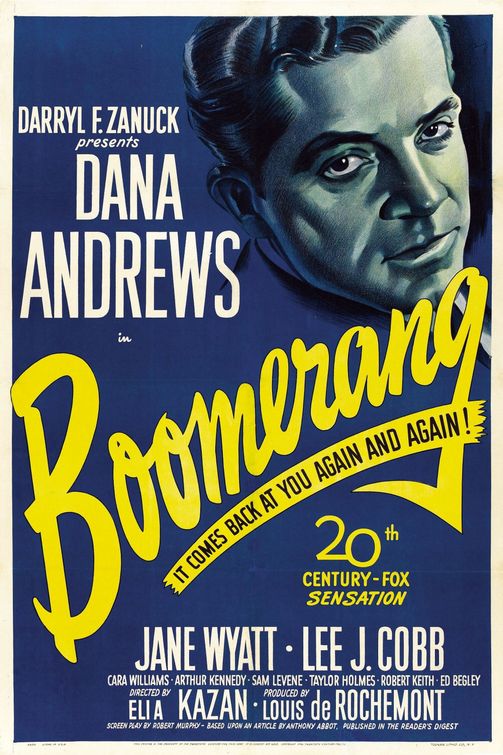

As it happens, Boomerang! fits nicely into a very distinct tradition usually called docu-noir. The tradition was virtually invented by Louis de Rochemont, who happens to be the producer of Boomerang! De Rochemont made his name producing the March Of Time newsreel series, essentially a breezier and more entertaining variant of the standard newsreel. He then became a producer of features at Fox. His first film, the docu-noir The House On 92nd Street, set the pattern for the new form.

Docu-noirs were police or government-agency (or sometimes newspaper) procedurals, usually based on real events and filmed in a quasi-documentary style, often in the locations where the real events occurred. Although they dealt with the same post-war anxieties that fueled the classic films noirs, they were radically different kinds of films, because they took the point of view of the authorities and they insisted that the official institutions of society could combat society's ills.

[Caution, plot spoilers ahead . . .]

The protagonist of a docu-noir might encounter corruption within the institution he served, but his personal integrity was always a match for it and allowed him to ensure that justice was done in the end. There was often, as in Boomerang!, a subsidiary character (played by Arthur Kennedy, above, in this case) who resembled the protagonist of a classic noir, an innocent man wrongly accused, dragged down by fate or official misconduct, but we never saw the story through his eyes — we saw it through the eyes of the official (or dogged reporter) who would save him.

There are no such saviors in classic noirs — the whole burden of which is to involve us emotionally in the nightmare of the trapped man, to show us the world from his point of view, to make us feel its oppressive weight. The protagonist of a classic noir might or might not survive his nightmare, but such salvation as he occasionally does find is likely to be provisional — there is rarely any suggestion that the world which generated his nightmare is ever going to change.

This is light years away, existentially, from a film like Boomerang!, where the hero has a dark night of the soul, chooses to do the right thing, defies the corruption of his bosses, frees the innocent man and goes on to become the Attorney General of the United States. It is, in short, a film which questions and criticizes but ultimately vindicates the American legal system, affirming the efficacy and ultimate triumph of moral action within it. If Boomerang! is a film noir then I guess Mr. Smith Goes To Washington is a film noir, too, and we need some other term to describe movies like Detour, Out Of the Past and Thieves Like Us.