In a very interesting comment thread on Facebook, sparked by some remarks in the press by Cotty Chubb about the film Unthinkable which he produced, John Tarnoff raised the issue of “4-wall digital” distribution. “4-wall” is the practice of renting a movie theater to showcase a film which hasn't gotten traditional distribution. It's usually been done in a major city, hoping to get press attention, which then might lead to traditional distribution. It still required expensive local advertising, usually in newspapers, and of course at least one costly photochemical print of the film.

But things have changed. Digital projection doesn't require costly photochemical prints, and online advertising, including peer-to-peer advertising, could theoretically reach enough people to fill a movie theater at any given showtime. The decline in attendance for traditional theatrical films, and the shrinking of their demographic appeal, is likely to continue, even though revenues will continue to flatline, more or less, due to inflated ticket prices (which is what 3D is really all about.)

4-walling suddenly seems like an interesting alternative to traditional distribution, since theater owners still need people marching past their concession stands and since the costs of 4-walling have fallen to within the capacities of independent producers — if they can figure out how to do it right.

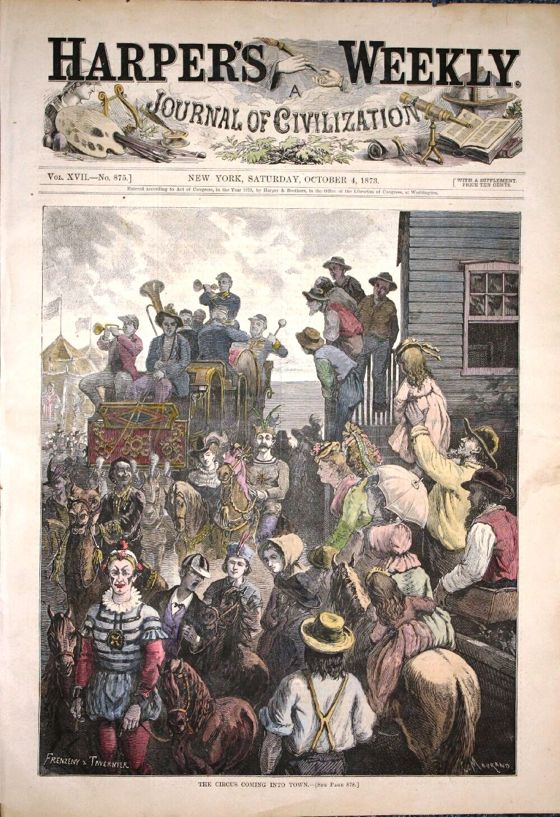

Doing it right is going to involve relearning the ageless techniques of exploitation and ballyhoo. Seeding mentions in discussion groups or on Facebook and Twitter is only part of the equation. 4-wall exhibitors are going to have to make some waves in the local community where the film is to be shown — which was the function of the classic circus parade. The performers of a circus would march through the streets of the town they were about to play, previewing their wares. This was an entertainment in itself, all given for free, to build interest and excitement.

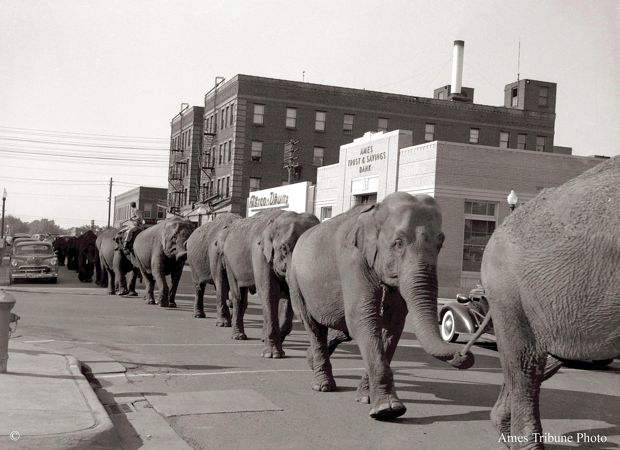

A free concert in a park or shopping mall might be the modern equivalent — or even a parade, done in collaboration with some local group with a connection to the film's subject matter. We're talking about relatively small towns here, places where a little free entertainment is a big event . . . but the train circuses played lots of relatively small towns and made most of their money from them.

We're also talking about films that don't cost too much to make — ones with budgets in the hundreds-of-thousands-of-dollars range, not the millions-of-dollars range. And that means they have to be really, really good films.

The theater experience needs to become an event as well — with the stars of the film in attendance, programs, ushers in character costumes (volunteers from the local high school drama club). And I mean “stars of the film”, not “stars” in the current sense of the word, because such stars won't show up in Cheyenne, Wyoming for a live appearance in a shopping mall or at a rodeo. All the creators of the films of the future will need to think of themselves as part of the traveling circus that the film will become.

The online communities that coalesce around certain films also need flesh-and-blood equivalents — a convenient venue, for example, where people who've just seen a film can assemble to discuss it and to bond. Such assemblies would be mighty engines of the word-of-mouth advertising that any film needs to succeed — and create the core of future audiences for future films from the same artists. These assemblies are also opportunities for merchandising — just like the CD and T-shirt tables at rock concerts.

Theater owners used to cook up ballyhoo like this, with the help of the studios, even back in the days when almost everybody in America went to the movies every week. Now that more and more people are declining to go to the movies, such exploitation has become critical.

Producers of small films need to wake up and take charge. The days are past when you could just feed your movie into the distribution machine (if you were lucky), do a little press in the big media centers, and hope for the best from newspaper reviewers and the audience.

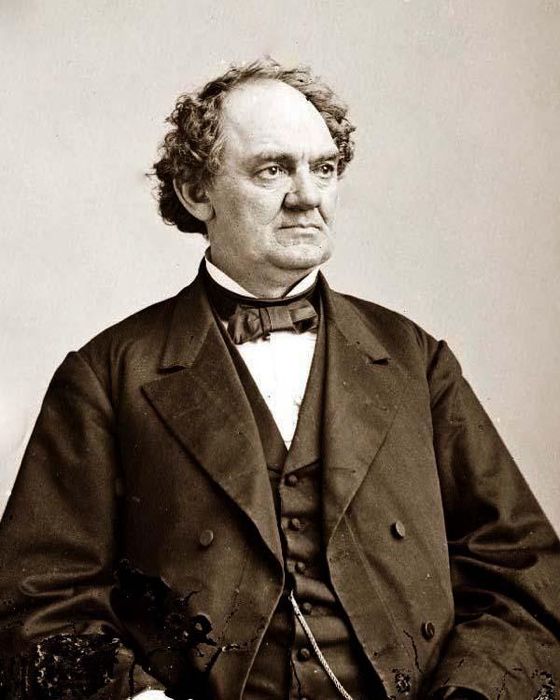

We need to revive the spirit of Barnum (above) — who would do anything, and I mean anything, to drum up interest in his attractions, at his museum or in the rings of his traveling circuses. He realized that ballyhoo is itself an entertainment, an art form — that people love to be bamboozled out of their pocket cash if the bamboozling is daring and spectacular enough . . . and if the first dose of it is free.

Ironically, in this virtual age of ours, the time has come for showmen to get back out on the road — to feed the virtual world with real-life hokum. This is what musicians have come to realize — their money today is made on the road, in live concerts, in providing unique experiences for their fans.

Of course, it will all be meaningless if the attractions, the movies, don't work for people — but that's another advantage of being out on the road. You find out what people want and don't want in the most direct and sometimes brutal ways. They teach you what kind of movies to make — in a way no focus group or demographic analysis ever could, and certainly in a way no studio executive trying to parse the box-office returns in Variety ever could.

To sum it all up as succinctly as possible — modern producers need to start thinking of themselves as showmen again . . . they need to abandon Hollywood, the motion picture capital of greater Los Angeles, and get some sawdust and elephant shit on their shoes.