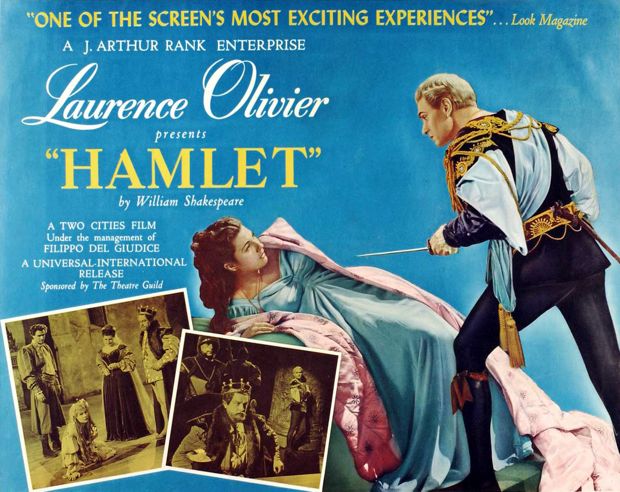

When we were 15, my friend Paul Zahl and I decided that Laurence Olivier's film of Hamlet was “over-directed” — whatever that means. Nearly a half century later, and having just watched it again on DVD, I am ready to pronounce a different verdict — it's badly directed, plain and simple, in most respects.

The black-and-white cinematography, with its endless swooping through miniatures, its moody superimpositions and backscreens, shows only the rarest trace of compositional skill, of plastic invention. All the performances are terrific, except Olivier's. His wimpy, fey Hamlet allows for no tension in the character. Shakespeare's Hamlet loses his manhood in the course of the play, but Olivier's Hamlet has abandoned his before the movie starts. Perhaps this is a function of Olivier trying to play younger than he is, but his boyish haircut and simpering manner simply read as weakness. If Hamlet is weak, if he's not a strong, smart, passionate man, where's the story — what does he stand to lose?

Finally, Olivier's decision to speak the great soliloquies of the play mostly in voice-over is a disastrous miscalculation. Hamlet is in part about “performing” the self — the self as performance. Shakespeare's soliloquies for Hamlet are not about letting us in on his character's deepest, truest thoughts — they're meant to show us a man trying to construct a self that he can find plausible as a basis for irreversible actions . . . and failing.

The convention of soliloquies spoken aloud to an audience is artificial, but in this play Shakespeare used the convention to make a comment about the artifice of thought, the artifice of self-reflection. In a film as self-consciously expressionistic as Olivier's Hamlet, what sense does it make to substitute the movie convention of voice-over for the stage convention of soliloquies when it sends such a different message?

Having said all that, I can't deny that Olivier's film is wonderfully entertaining, because Shakespeare's language is wonderfully entertaining, and no interpretation of Shakespeare's story and characters can ever trump the playwright's ruthless determination not to interpret them. As long as his characters speak their lines intelligibly, they are alive, immortal.

This film records the extreme skill British players of the last century developed for speaking Shakespeare's language naturally, without losing its poetry, its formal eloquence. It's absurd to declaim Shakespeare like holy writ, but equally absurd to toss it off like casual conversation. Nobody in the history of the world has ever spoken casually in strict iambic pentameter and rhyme. There is a middle way, and Olivier's cast members have mastered it.

Olivier has mastered it, too, of course, and if you listen to recordings of his readings of the lines in this film, they dazzle with their subtlety and modulation and invention. They don't contribute to a convincing portrayal of Hamlet in the film itself, but they are the product of extraordinary craft and art.