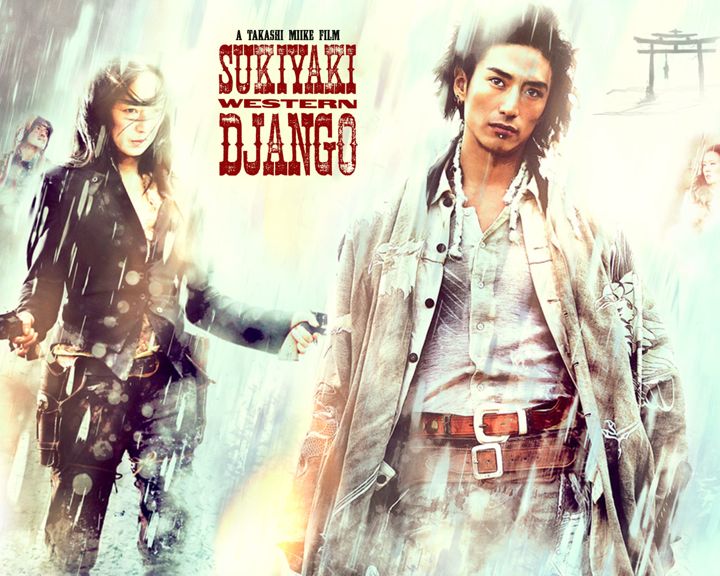

Facebook friend Ray Sawhill, a sharp critic of movies (and other things), remarked that the trailer for Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained made the film look like second-rate Takashi Miike. That was enough to send me to Miike’s Spaghetti-ish quasi-Western Sukiyaki Django Western, which I’d never seen.

Miike and Tarantino are friends, and Tarantino (above) has a small role in the Miike film. I wondered if Miike’s work could really stand up to Tarantino’s, which for all its faults I like a lot. I couldn’t compare Miike’s “Western” to Tarantino’s Django Unchained, which I haven’t seen, of course, but could compare it to the Tarantino films I’ve most enjoyed, like Pulp Fiction and Inglourious Basterds, which also offer eccentric takes on old genres.

I have to say that for me the Miike didn’t hold up at all to Tarantino’s best. Sukiyaki Django Western is set in a fantasy “Old West” in which 19th-Century America and 19th-Century Japan have somehow merged. This is conceptually interesting, because the original Spaghetti Westerns were inspired by Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, a kind of goof on American Westerns, though in a Japanese setting.

Miike goofs on these goofs on a goof and the whole thing starts to seem like a purely theoretical, intellectual exercise, a commentary on mere style. Miike’s fantasy West has no roots in anything but style, and his characters never rise above the level of photocopied icons. It’s impossible to develop any real feelings for them — apart from an instinctive recoil at the horrible ways they often die.

Tarantino can be accused of this same obsession with cinematic style over dramatic substance, and sometimes, as with the Kill Bill films in my opinion, the accusation is fair. But Tarantino knows how to vary the pace of a film, how to use extended sequences of dialogue to create suspense, how to invest his iconic characters with enough quirkiness and depth to allow identification with them. In his best films he uses all those skills well.

Sukiyaki Django Western is filled with startling images but they fly past at a furious pace, as they do in most modern Hollywood action films. Probably the worst failing of the film is one it shares with many of the classic Spaghetti Westerns, and most modern Westerns, too — an emphasis on gunplay as the single defining aspect of character. In 1968, Larry McMurtry wrote this, in a book of essays on Texas called In A Narrow Grave:

The master symbol for handling the cowboy is the symbol of the horseman. The gunman had his place in the mythology of the West, but the cowboy did not realize himself with a gun . . . Movies fault the myth when they dramatize gunfighting, rather than horsemanship, as the dominant skill. The cowboy realized himself on a horse, and a man might be broke, impotent, and a poor shot and still hold up his head if he could ride.

McMurtry was talking about the Hollywood Western, and his observation is valid, but only up to a point. Horsemanship may not have been dramatized as obviously or as regularly as gunfighting in the Hollywood Western, but until modern times it was always given its due. It was noted, given prominence, visually if not always dramatically.

The stars of the genre were always superb horsemen — something you just can’t fake, even with a push-button movie horse. Especially in the classic American Westerns of the Fifties — those by Ford, Boetticher and Mann — the way a man sat and handled a horse was a key to his personality. Ford became obsessed with the poetry of Ben Johnson’s horsemanship and tried to make him a star. He never succeeded in this, but Johnson is given aria-like interludes of riding in many of Ford’s great Westerns — passages of cinema that elevate Johnson to a transcendent heroism beyond the reach of many actual stars.

As in many modern Westerns, the horses in Sukiyaki Django Western are just props. Any feats of spectacular horsemanship are created with special effects. The actors try to look cool on horses, and sometimes succeed, but they never convince you that they belong up there, have spent a lifetime up there.

We’ll see how Tarantino handles horses and horsemanship in Django Unchained. (That’s a still from the film above.) It will be one measure of the film’s nature — an invigorating new take on the genre or just another pointless goof on a goof on a goof.