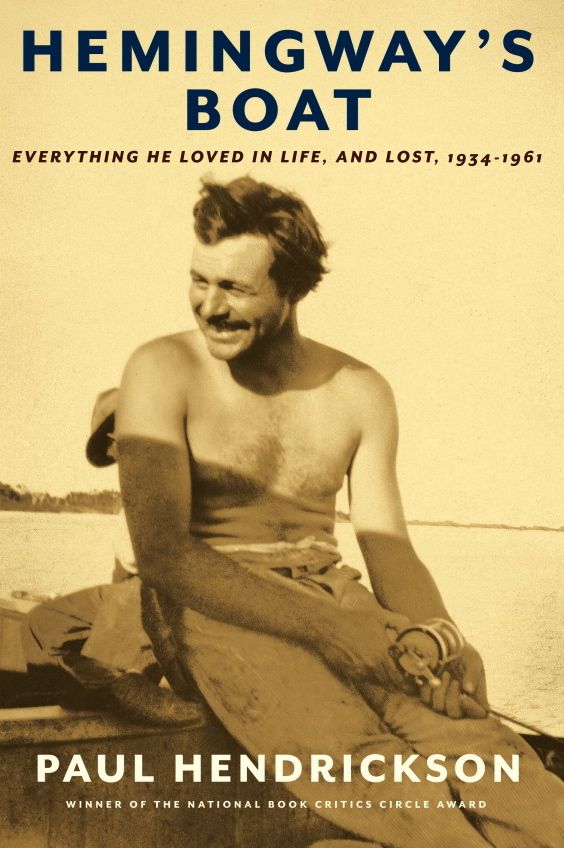

This is the best book ever written about Hemingway because it has more of something few Hemingway books have in any amount — genuine compassion. The writers on Hemingway who idolize him, however circumspectly, don’t think he needs compassion, and those who despise him, however circumspectly, don’t think he deserves compassion.

We all need compassion, of course, and the scriptures say we all deserve compassion, even if we don’t. (This is the mystery of Grace.) In any case, few lives cry out for compassion more than Hemingway’s, and few men deserve it more, even on non-scriptural grounds, if only for the contrast between the intense joy and enlightenment his work has brought to so many people and the intense suffering he endured, especially towards the end of things.

Click on the image to enlarge.

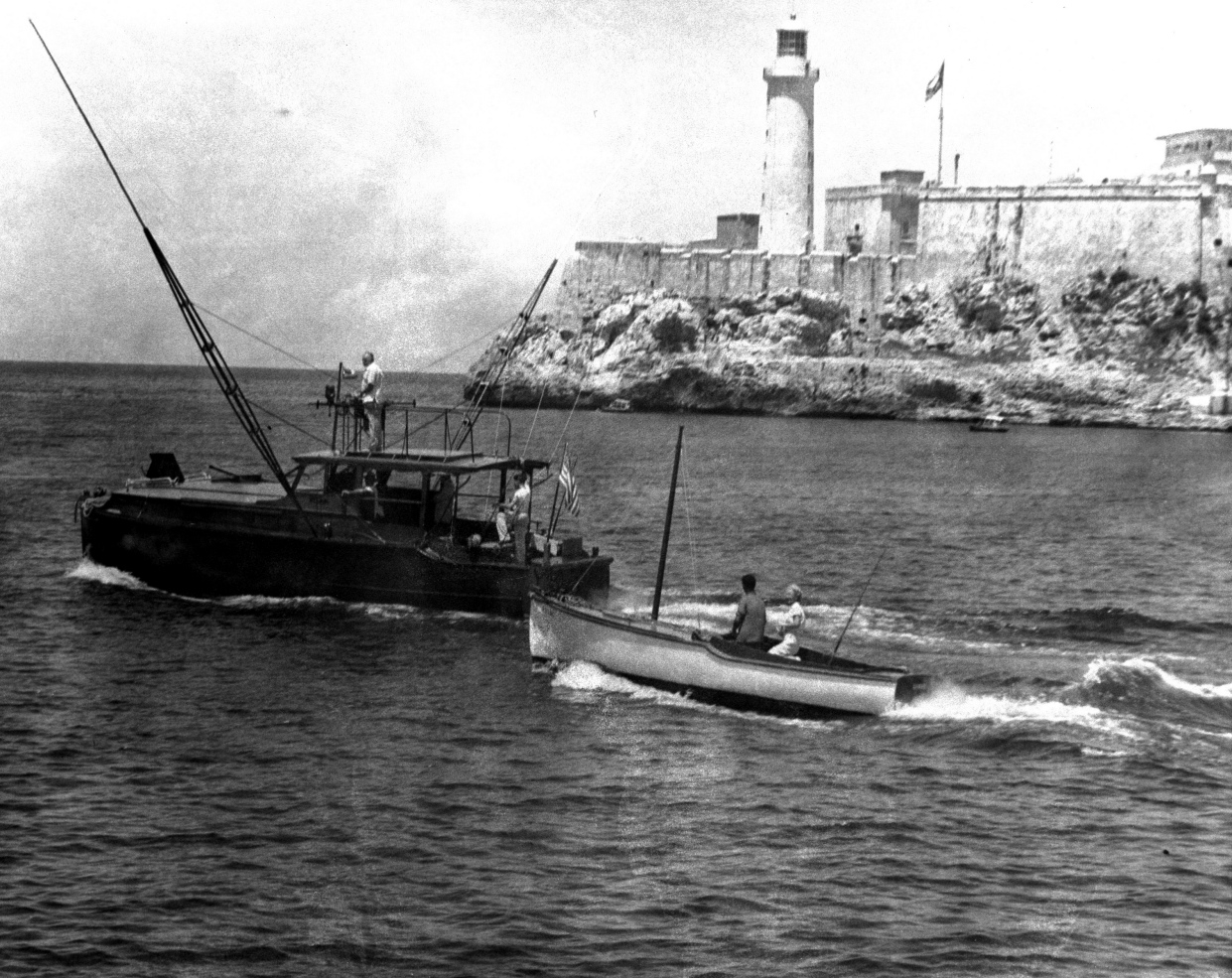

Hendrickson’s book is not a biography — it’s a meditation on Hemingway’s 38-foot fishing boat Pilar (above, heading out to The Stream from Havana Harbor) and what it meant to the man. Hendrickson weaves into this meditation further meditations on the lives of people who shared time on the boat with Hemingway, especially the ordinary folks Hemingway befriended and was kind to.

Central to the book, though, is Hemingway’s youngest son Gregory, who led a bizarre life that careened between accomplishment and misery, the latter caused mostly by his obsession with cross-dressing, which Papa caught him doing for the first time when the boy was around nine. Gregory eventually had a sex-change operation and tried to make his way through life, somewhat desperately, as Gloria Hemingway:

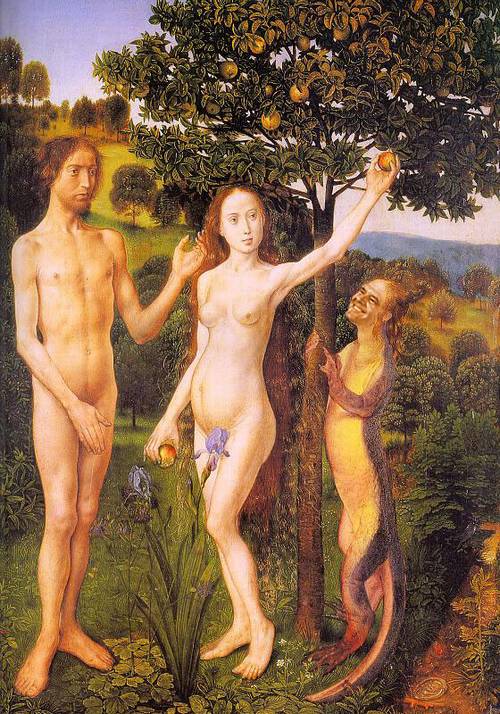

The obvious contrast between Papa’s macho posturing and his son’s sexual confusion is neither interesting nor illuminating. What’s interesting and illuminating is the gender-crossing theme that runs through so much of Papa’s fiction, present even before he discovered he had a cross-dressing son, and developed most extensively in his unfinished novel The Garden Of Eden, written in the Fifties when his son’s sexual confusion was causing the family no end of embarrassment and pain.

It’s almost as though his son’s obsession caused Hemingway to delve even deeper into the theme, because it was there in his own psyche and because it would have been unmanly to dodge it.

Hendrickson doesn’t arrive at quite this conclusion, but I believe that Hemingway discovered in sexual love a mystery that both excited and disturbed him — the sharing of identity with a female that went beyond sympathy and understanding, that became, at least on some level, an existential doubling.

A man who was only about macho posturing would have denied this, avoided it — but such was Hemingway’s courage as an artist that he could not let the phenomenon alone, even if he could not quite make sense of it.

Some biographers have tried to relate the phenomenon to the fact that Hemingway’s mom dressed him as a girl in his childhood, and sometimes pretended that his older sister Marcelline was his identical twin — as though he were trying to reenact this situation in adult life. I think this is psychobabble. Hemingway discovered something extraordinary in sex, an interpenetration of sexual personae, of gender, that is very mature, very authentic, very profound.

Paul of Tarsus wrote, “In Christ there is no male and female” — probably the most radical statement to be found in the scriptures of any religion. Hemingway had an experience related to this insight in the throes of passion, and it enchanted him even as it bewildered him. In trying to write about it, he went out past where he was comfortable, both as a writer and and as man. The important thing is that he kept on trying to write about it, almost to the end.

You can see how the image of Pilar works in all this — a boat he took out into the Gulf Stream as often as he could, from which he cast out bait to bring up monstrous miracles from the uncharted depths, rehearsing again and again what he felt was his duty as an artist, as a writer of true things.