The Sun Also Rises is a young man’s book. Hemingway wrote it when he was 26 years-old, at a time when he was beginning to feel his oats as a writer, beginning to feel that he had it in him to become a great writer. He was hanging out with the smart set of English and American expatriates in Europe, and with the fast set there, too, which intersected with the first set to a degree.

It was a time in his life when all his eccentric friends seemed extraordinary, all their antics dramatically resonant in some way, all their follies witty. He came to have a different view of these friends, but he set a number of them down with enough precision in this novel that we can judge them for ourselves — see past whatever Hemingway may have seen in them at the time, a kind of tragic desperation, to something that seems more like frivolous self-indulgence.

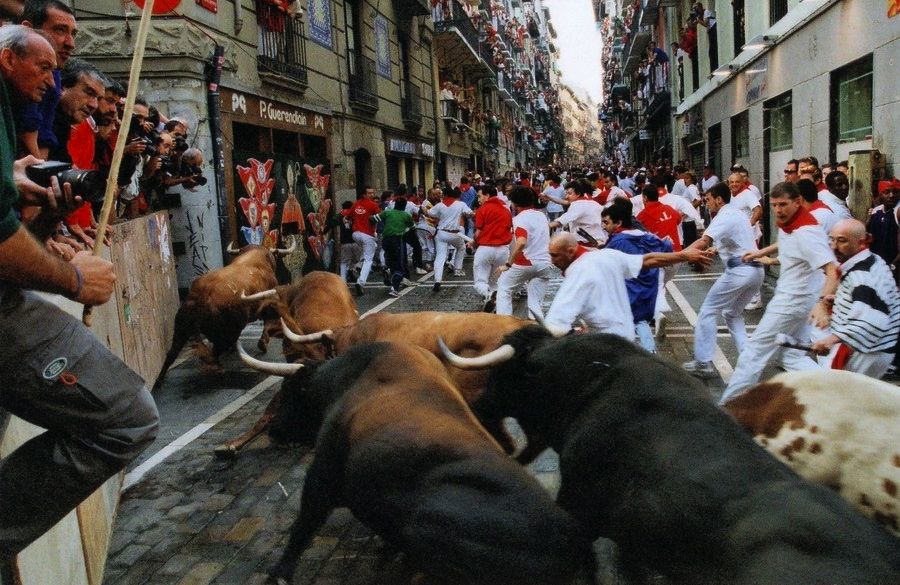

Which is to say that the grand ambition of the novel doesn’t quite stand as fulfilled — the attempt to chart the tragedy of a generation, scarred by war and lost to itself. The one character who is literally scarred by the war, the narrator, made impotent by a war wound, is the one character who seems spiritually whole and serious, though ravaged by regret. His wound is too literal, an objective correlative that isn’t really dramatized in the group portrait of his friends.

What stands is the crystalline portrayal of times and places, the vibrant documentation of a certain type of person, in prose that is still startling today for its force and purity. It’s Hemingway prose at its best, before he grew self-conscious about it, before it took on the mannerisms which, in his later work, are so easy to parody.

The prose and the dialogue of The Sun Also Rises are beyond parody — beyond easy imitation, almost beyond emulation. They create an immediacy of felt experience as vibrant as the memories of real events in our own lives. The novel, compromised as it may be on some levels, constitutes one of the greatest of all literary achievements, one that comes alive on the page with astonishing vitality as often as one cares to read it.

Hemingway retained the power to write such prose almost to the end of his life — what he lost was the power to sustain it the way it is sustained in The Sun Also Rises and to nearly the same extent in A Farewell To Arms.