. . . is almost unbelievable.

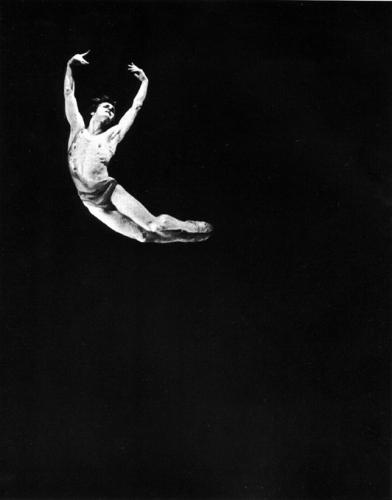

He gets a lot of it, really a lot of it, and when he's at the peak of his ascent he seems to pause for a moment and then decide to come back to the earth.

Great classical ballet dancers give the same impression at the tops of their jumps. It's an uncanny illusion created by a visible relaxing of the muscles at that moment of apex, very slight, but perceptible. It seems to suggest absolute calm, absolute unconcern about the landing. It seems to suspend time along with the rules of gravity.

White does a lot more complex and astonishing things than his straight air move, a required element in the competition which he usually places at the beginning of his run — but his execution of the straight air move is an announcement of sorts, asking us to look not just at what he's doing but at how he's doing it.

It is the statement of a theme, an artist's manifesto.

The finals of the men's halfpipe in Vancouver last night made White's aesthetic ambitions clear. Going into his second run, the last run of the competition, he had already secured the gold medal. He could have slid straight down the bottom of the halfpipe to the finish line and collected his prize. But he chose to outdo his gold-medal-winning first run, and he chose to finish it with his new signature move, which he hadn't yet unveiled in the competition — the double McTwist 1260, a move so complex that it can only be followed clearly in slow motion.

[Image © 2010 New York Times]

He didn't have enough speed going up the wall to get all the air he needed for this last move, but he decided to use the air he had. He performed the move with barely enough time to get his board pointed down the side of the wall and his weight over it for his landing. He hit the snow off-balance but somehow found it again — by force of will, it seemed.

His second, wholly unnecessary run scored higher than the run that had already won him the gold. It was sublime, Homeric, transcendently beautiful.