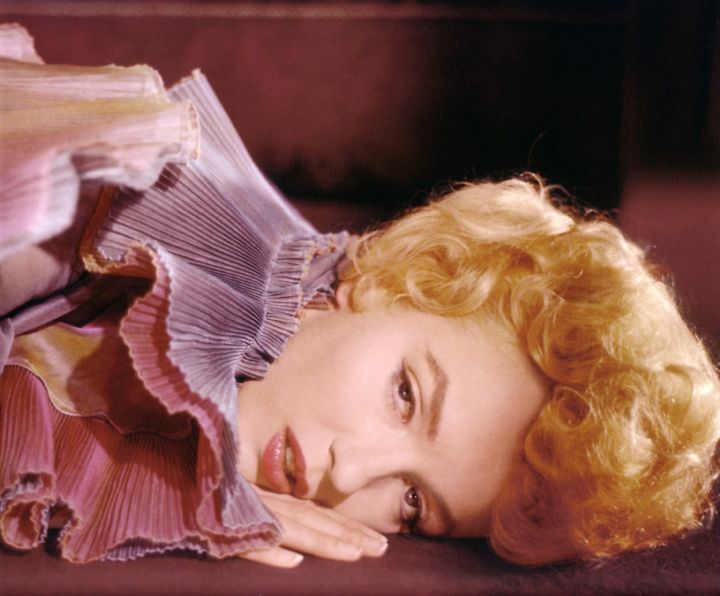

In many of her films, Marilyn Monroe played “Marilyn Monroe”, a relatively fixed persona, the one that made her a star and an enduring icon. “Marilyn Monroe” was a slightly ditzy, intuitively wise blond bombshell. She spoke in a little-girl voice and paraded her sexuality with a cheerful, almost infantile innocence. But there was a lot more to it than that.

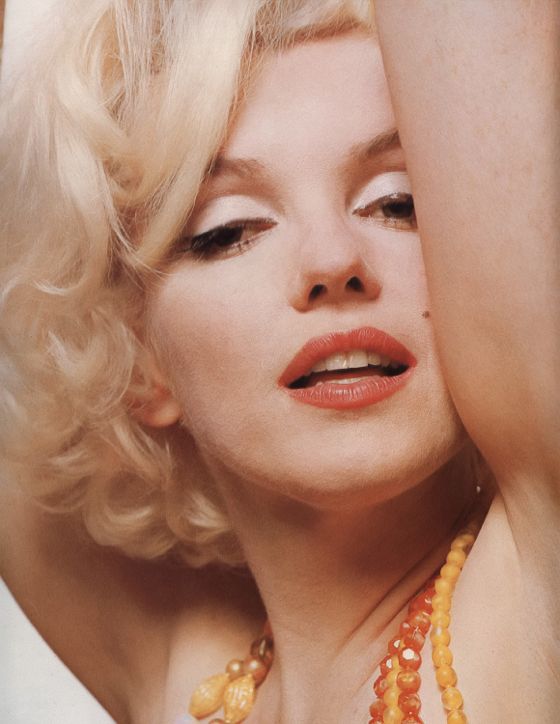

Monroe the actor presented this persona with an elegance and precision that required artfulness of a very high order. Her control over her voice was considerable, her control over her body sublime. You can see this most clearly in her musical numbers. She did not have a naturally strong vocal instrument, which makes her witty and/or dramatic readings of songs that much more impressive. She was not trained as a dancer, which makes her dance moves, always so lyrical and finely executed, that much more surprising.

This physical control over her body is present in all her screen appearances, even in purely dramatic roles. She knew how to possess space as only the greatest screen actors can. She is one of the few sound-era movie stars who could have been just as stellar in the silent era. Her style of movement involved extreme virtuosity. But there was a lot more to it even than that.

Monroe's virtuosity as a performer was so well calculated and well executed that it introduced an element of irony into her style, contradicting the ditzy side of the “Marilyn Monroe” persona, emphasizing the intuitively wise side. This could be disturbing, anti-erotic, even, suggesting that the real joke in all her comedies might be on anyone who took that persona too seriously. She created or perfected a powerful erotic style while at the same time critiquing it — but there was never a hint of condescension or parody, of camp, in the critique. Compared to Mae West, or Madonna, or Lady Gaga, performers who have worked the same vein of erotic irony, with a leering wink or a hip sneer, Monroe had the touch of a lyric poet.

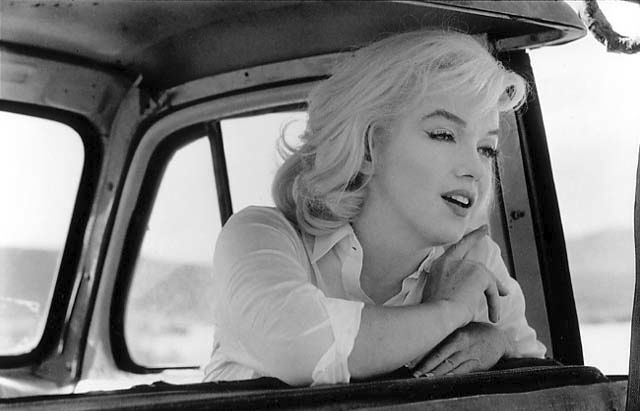

Most miraculous of all, Monroe was able to translate this persona into her non-musical, non-comedic roles. “Marilyn Monroe” was the creation of the actor, her writers and directors, and her public — but it wasn't mere artifice. There was a psychological truth at the heart of the persona. Many real women present themselves as childlike but sexual, exhibitionist but innocent, scatterbrained but deeply knowing. The strategy reflects both an inner insecurity and a canny appreciation of male insecurity. In her straight dramatic roles, Monroe was able to translate this insight into more naturalistic terms, fold it into characters whose strategies of self-presentation are perfectly recognizable as those of people we have all met in ordinary life.

The insight, in whatever form it's manifested, results in a resonant paradox. The ability to manipulate men, to fashion a mask that will attract and console them, is a form of female power. But it is also a source of female despair — what woman wants a man so easily manipulated? What woman doesn't want to tear off the mask and be seen for who she is — even, and perhaps especially, if she herself doesn't know who she is? Sexual love is undoubtedly a game, but it's a game that promises to reveal the deepest truths about those who play it.

The ultimate question Monroe the artist asks is — how can the game be played if one of the players doesn't know it's a game or, if he does know, doesn't know how to play it very well? In the era of collapsed manhood that followed WWII, asking that question made Monroe an international sensation, an icon, a crucial cultural figure. She remains sensational, and essential to American culture, because the question still haunts us, still has no answer.

Some might argue that the “Marilyn Monroe” persona was one born of limited range and skill, but this is like denigrating a great shortstop because his athletic prowess doesn't mirror the athletic prowess of a great boxer. They're playing different sports, in different arenas. If you prefer one to the other, make sure you've got tickets to the right event — and if you find yourself at the wrong event, don't blame the athletes who are playing a game you don't enjoy or appreciate.