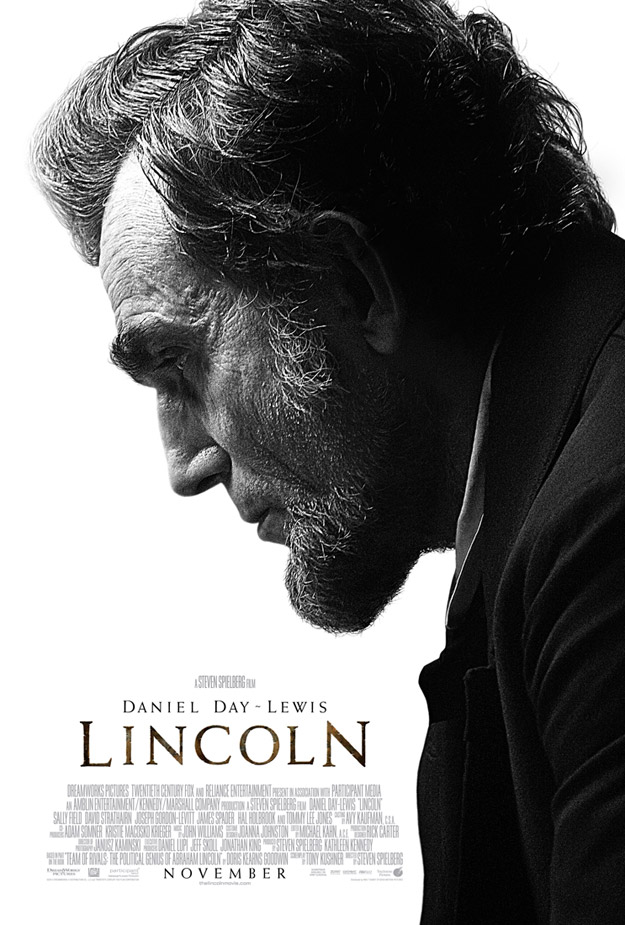

The trailers for Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, and the poster above, which depicts the man as a kind of bas-relief sculpture, suggested that the film was going to be a chore to get through — a pious civics lesson about the martyred saint who freed the slaves and saved the Union.

In fact, the film is quite entertaining, thanks to Tony Kushner’s lively and intelligent screenplay and a number of very good performances, by Daniel Day Lewis, Sally Field and Tommy Lee Jones in particular. Lewis’s interpretation of Lincoln is the best of all those that have been done in movies, simply because he makes Lincoln seem like good company, as by all contemporary accounts he was. This is something even Henry Fonda, likeable as he was as a screen presence, couldn’t quite pull off except in brief moments.

The film takes a brutal look at the mechanics of American democracy, at the skulduggery and corruption that grease the wheels of even the most idealistic legislative achievements. This is paralleled by a visual evocation of the shadowy and grimy physical world of the 19th Century — you get a sense from watching this film of how bad most people of that time probably smelled.

The film fudges a bit on Lincoln’s views about integrating freed blacks into American society as citizens — he probably wasn’t as sanguine about the prospects of that, as open to the idea, as he’s presented here. On the other hand, it’s fair to suggest that his thinking on the subject might have evolved had he lived longer — that there were the seeds of such an evolution in his heart.

What’s less forgivable about the subtext of the film is the suggestion that the questionable legal and moral tactics Lincoln used during the greatest crisis that ever faced the nation, a time of armed conflict on a massive scale, might be applicable to our own current President, whose legal and moral transgressions against the Constitution and liberty itself haven’t unfolded in a similar context.

I don’t think there’s any doubt that Kushner and Spielberg had some such apology for Obama in mind when they made this film — and wanted to imply that noble intentions can justify almost any act by a President. That’s a stretch — and a dangerous one.