The Western isn't dead — it never was. It abides, through fruitful times and fallow times — a rich soil always capable of putting up unexpected shoots.

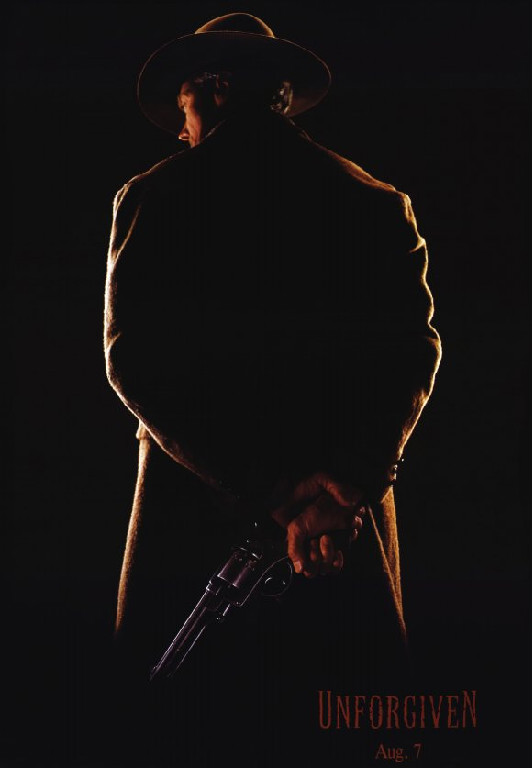

A bestseller, like Larry McMurtry's Lonesome Dove, can inspire a classic Western, which the mini-series based on the book surely was. A great screenplay, like David Webb Peoples's Unforgiven, in the hands of a great director, can produce a critically-acclaimed box-office hit.

Unforgiven was much more than that, of course — it is now generally recognized as one of the greatest Westerns ever made, one that can stand comparison with the classics of the genre, and with all but the very best Westerns of John Ford.

Since Unforgiven was made in a fallow time for Westerns, it naturally reflects this. It is part of a tradition that arose in the Sixties when the Western seemed to be dying off as a viable commercial genre — the twilight Western. This tradition concerns aging heroes who set off on one last adventure, mirroring a feeling that the Western itself might be heading for the last round-up. Valedictory in tone, it actually wants to assert that the aging heroes are still with us, that their values still matter.

The twilight Western tends to be revisionist, painting a darker and grittier vision of the Old West than the older classics, and often incorporating a female perspective — these are its nods to modernity, on one level, but also its witness that the Western genre is still alive, still capable of evolving, of reflecting contemporary issues and ideas.

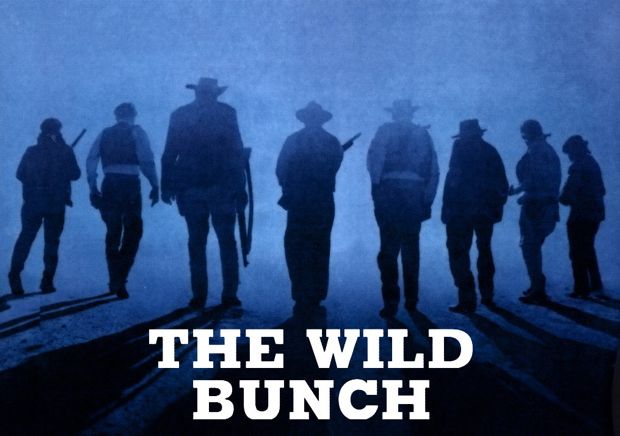

The makers of anti-Westerns, like Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch, believed that the Western was played out, and proceeded to deconstruct it, to suggest that the Western myth was all a lie — that was their nod, or surrender, to modernity. It was a delusion, as the phenomenal success of movies like Lonesome Dove and Unforgiven proved, but a delusion with great cachet for filmmakers and studio executives who came of age in the Sixties and Seventies. For them, the thrill of killing off the traditions of their fathers festered and metastasized into an industry truism — modern audiences don't like Westerns.

The truth is that modern audiences don't like anti-Westerns, the only Westerns that present-day Hollywood thinks are cool. Every time a new anti-Western flops, it seems to confirm the truism. When a new Western that celebrates the classic virtues succeeds wildly, it's seen as an anomaly.

If the Coen brothers' True Grit, opening this Christmas, succeeds, Hollywood will not see it as the success of a Western. As a Hollywood producer recently remarked to a friend of mine, reflecting on a possible revival of interest in Westerns, “The Coen brothers are their own genre.” There's some truth in that, of course, but only up to a point, and that point is reached when the Coen brothers tackle a classic Western tale like True Grit.

Eventually, the glamor of the anti-Western will die out, with the rise of new generations of directors and producers untainted by the follies of the Sixties and Seventies. The Western will still be here, its soil richer than ever from a long fallow time, ready to produce a new harvest of stories and adventures. The passing of the twilight Western will signal the true renaissance of the form — new, young stars will take up the reins as protagonists of the revived Western, and blaze their own trails into the heart of America's most precious and enduring myth.

The still of Robert Duvall is captivating. It really does speak to the depth and quality of that story. Or any story. There moments in films, that if seized upon, as you have done here, take it to a whole new level of richness and life understanding.