On our first full day in Jackson Hole several of us made an expedition out to the Lawrence S. Rockefeller Preserve, part of the Grand Teton National Park, to see a new building that John had designed there, the Preserve's visitors' center.

John is an unusual architect and an important one — for several reasons. Although he does world-class work, he has chosen to maintain a primarily regional practice. He grew up in Lake Forest, Illinois and in Hollywood, where his dad worked as a screenwriter, but his roots in Wyoming go back to his teenage years, when his parents bought a large ranch on the Green River south of Jackson. He started his professional practice in Denver but after a few years he moved it to Jackson, where he prospered building homes for the rich and famous attracted to that part of the world, as well as executing commercial and civic commissions in the area. He's carried out commissions elsewhere — including two skyscrapers in Denver — but he's concentrated his creativity mostly on local projects.

He decided early on to go his own way, designing buildings that pleased him and pleased his clients, rather than ones that followed the tiresome architectural fashions of the day, which for much of the 20th Century favored severe, multi-useless spaces.

His buildings echoed a frontier style, rustic and simple, often borrowing elements from the grand park lodges of the Teddy Roosevelt era, with a dash of Frank Lloyd Wright's Japonisme, but he never indulged in pastiche. He created complex and inviting spaces that were in a kind of dialogue with the big skies and grand vistas of northwest Wyoming. Like the simplest log cabins from pioneer days, his buildings have the quality of refuges, but they also have the wit and daring of a more contemporary style. I don't know any other buildings quite like them.

Now, of course, the architectural establishment that he mostly ignored has discovered him, and recognized his work with various awards. The visitors' center at the Rockefeller Preserve was a very prestigious commission, which John's firm won not because he was “local” but because John's design was stunning. Stunning but simple, revealing its magic subtly.

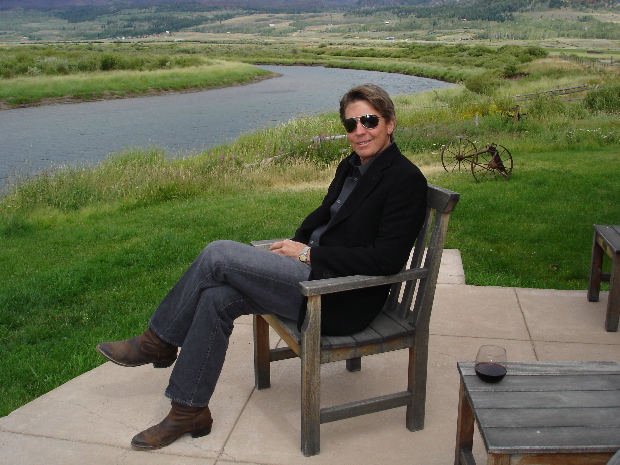

Look at the picture of the structure at the beginning of this post, which records the view of it you get approaching it on foot from the parking lot. It may, at a first, casual glance, seem like a utilitarian farm building, until you notice the elegant curved and slatted front, which projects the building forward into space . . . quietly.

Coming closer, you discover thin metal struts distributing the weight of the roof in surprising ways and also adding an “abstract” (though eminently practical) design element. The building also appears at first to be more or less rectangular and self-contained, but on approaching closer a wing behind it is revealed, attached at a right angle, creating a court-like space in the V between the wings, with a porch (pictured above) that further defines the implied court.

The building's design is distinctly modern in many ways, but it looks as though it's always been there — instantly part of the history of the park. It fits in to the continuum of frontier building, but carries it forward. It's neither highbrow nor lowbrow, neither modern nor post-modern, neither ironic nor nostalgic — it's just great. Like all great art it establishes its own category.

We walked away from our visit to the building enlightened.

The ability to create with space is one of the weirdest of all artistic gifts — weird because there's no language quite precise enough to describe its processes or its results. This is true of dance and sculpture and cinema as well as of architecture. We can talk clearly about the five positions of classical ballet, about the techniques of carving wood or marble, or casting in bronze, about the strategic choices involved in positioning or moving a motion picture camera in space, about the ways and means by which a building is constructed, but the link between these things and the way they can make us feel is elusive, mysterious.

And this is finally very odd, because the mystery is connected to things about space that we know very intimately, if unconsciously, from everyday life — from dancing, from playing sports, from the rituals of courtship and lovemaking, even from driving on crowded highways. Artists who create with space are telling us things we know without knowing.

Nothing I could write about John Carney's Western buildings could possibly convey what it actually feels like to move around and through them. Their spaces can't be “quoted”, like the words of a text or a phrase of music — they can't be “reproduced”, even crudely, on a page like a painting or a work of graphic art. In the end, you just have to go up to Wyoming and walk around and through them yourself.