Paul Zahl, the Preacher From the Black Lagoon (see The Zahl File), revisits a commercial disaster from days gone by — the 1969 version of Goodbye, Mr. Chips:

A MOVIE WITH SOUL

by Paul Zahl

I am beginning to know James Hilton's books and the movies made of

them, such as Lost Horizon, in two wonderful versions; Random Harvest,

which is an almost perfect elegy to selfless love; and Goodbye, Mr.

Chips, also in two wonderful versions.

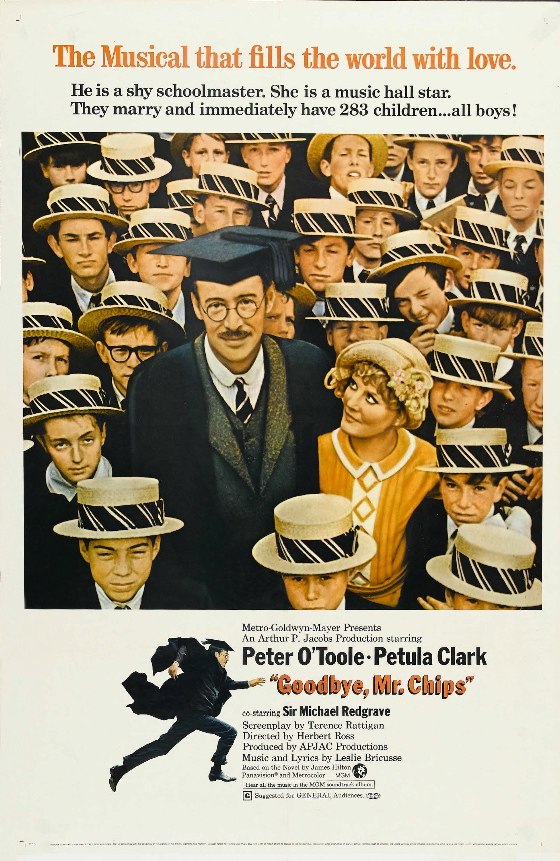

The second version of Chips, which bombed in 1969 (with the exception

of Pauline Kael's memorable praise), is an interesting case of a film

that more or less disappeared after its initial showing, became almost

notorious for its over-dubbed and stream-of-consciousness songs, and

co-starred the now less-remembered English pop star Petula Clark.

A personal interest in James Hilton, together with an interest in the

English playwright Terence Rattigan, led me to this movie recently,

which was released on DVD last January. And yes, it is an odd

collection of things — a familiar drama (or so it seems at first) of

life in an English boarding school; a use of idyllic outdoor long shots

and zoom effects that are like ads for Tab, or even Coke, back in the

'60s; spectacular and also heavily edited musical numbers within a

story concerning a Latin master of the 1920's; and in the heart of it,

right at the core of it, a love story that rings completely true.

In short, this is a movie with soul, which is also greater than the sum

of its parts.

After watching two versions of Terence Rattigan's The Browning Version,

both of which were filmed on the same location (i.e., Sherborne School

in southern England) as the 1969 Chips, I felt saturated with this

elite context. (The first version of The Browning Version, with Michael Redgrave, is illustrated above.) Is there much left to say, after these two persuasive

works, about the introversion and disappointments of prep school

teachers of Latin and Greek? Well, Rattigan must have believed there

was, because he took a familiar story, Hilton's novella of Brookfield

School, and batted it straight into the stratosphere.

His script, which now focusses almost completely on the love story of

Mr. Chipping, played by Peter O'Toole, and the unlikely love of his

life, played by Petula Clark, is literary and beautiful, full of

Classical allusions yet uncontrived. When Rattigan puts the Ancient

Greek maxim “Know thyself”, together with the God Apollo, at the

turning point of the story, it is fully apt and touching and true.

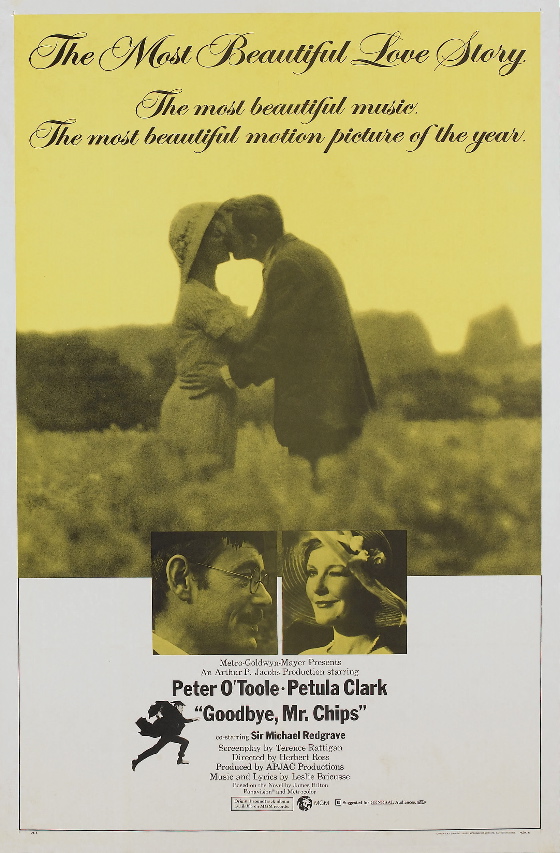

He also writes a scene between the two meant-for-each-other lovers,

filmed by the Victorian greenhouse at Syon House on the Thames, which

is as affecting a proposal of marriage — it is basically she who

proposes to him, yet with no tenor of forwardness — as anything of its

kind on film. Incidentally, I write as someone who has performed

hundreds of marriages and who gladly embraces Lloydville's title, Preacher From the Black Lagoon.

How does a movie acquire soul? We have an impressive script by a

master, Terence Rattigan. We have a great theme from James Hilton: the

transformation in real time and life that is effected by a devoted

woman in relation to a shy misunderstood schoolmaster, and the

consequent effect of the couple's marriage on an entire community,

Brookfield School, petty, political, and witchy. Yet these two

elements don't fully account for the movie's soul, which means you

start crying by the middle of act two and can't stop until way after

the end.

I think there are two other things that make Chips something like a

great movie, although probably not a great movie in the way of

cinematic art. The first is its visual style, which, as I said, is

full of long shots of the heroine and hero, with flowers in the

foreground; constantly changing colors to mirror the emotions of the

leads; many zooms from high up (God's eye!); and basically the most

accomplished style of the kind of thing Dan Curtis was doing in his

made-for-television horror movies of the same era: a little arty,

consciously 'visual', and plain pretty. It works here and you probably

wouldn't alter a thing. Thus the sequence at Pompeii and Paestum works

because the honey-colored marble of the sublime ruins matches the early

love of the surprizing surprized couple.

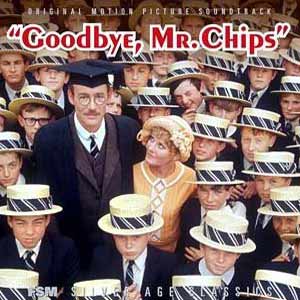

The second added thing in this wondrous movie is the music. The songs

are by Leslie Bricusse, who wrote “Stop the World, I Want To Get Off”;

and the instrumentation is by John Williams. The songs were considered

forgettable when Goodbye, Mr. Chips first opened, without much for

tunes. Yet they are mostly sung by Petula Clark and Peter O'Toole as

narrations rather than lip-synch performance. They are internal

monologues. They are therefore true to life. Petula Clark's song

“Apollo”, for example is subtle and everything that the word “nuanced”

is now supposed to mean. And I will guarantee something to the readers

of this blog: If you see Chips and do not go straight to YouTube or

iTunes and listen to “Fill the World With Love”, over and over again,

you had better check to see if you still have a heart. To be honest

with you, now that I know what that Bricusse-composed school hymn means

in light of the powerful story in which it figures so prominently, I

don't ever want to sing anything else again. (Maybe “Be True To Your

School” by the Beach Boys, but nothing more, ever again.)

So, here is a movie with soul. Goodbye, Mr. Chips from that hinge year

1969 is hard to explain. It's got Hilton in the first stratum,

Rattigan in the second, sublime if ever so slightly cheesy visuals, and

introspective songs that work, partly because they do not overwhelm the

other elements.

There is a fifth element, however, one more thing, to add. There is

Peter O'Toole and Petula Clark. These actors were made for each

other. Clark embodies a kind of heroine that you rarely see any more.

(I married one 36 years ago.) She loves her husband, supports him

with everything she has and thus brings out qualities in him that he

never knew he had, and she's humble while having a kind of luminosity

— a word like “nuanced” which suffers from over-use — or inner

spiritual strength that is contagious in this self-absorbed world.

Katherine Brisket, which is the name of Clark's character, is the

strongest entity in the entire movie. Yet her life's work is love.

That is why the bull's eye center of Goodbye, Mr. Chips is the scene

when Mrs. Chipping takes the entire student body and faculty to a new

and noble level as she leads them, not by design, in the school hymn

“Fill the World With Love”. This is not dumb! It completely works.

No wonder O'Toole's character falls in love with her, defends her, and

establishes an unforgettable rock of a life with her.

Goodbye, Mr. Chips is now available on a beautiful DVD, its soundtrack

also available on a connoisseur's three-disc CD from Film Score

Monthly.

Oh, and I just took a look at Joanna, made one year earlier in England

with Donald Sutherland and Genevieve Waite (and Rod McKuen — listen to

the warm) in order to get some perspective on the period. Odd isn't

it: I loved Joanna back then, and thought Chips was dumb. Now I love

Chips and think Joanna is the queen of dumb.