You won't hear this opinion put forward on the cable news channels, because the commentators on the cable news channels are, for the most part, pathetic clowns totally divorced from common sense and from independent thought of any kind . . . so I'm just going to have to say it myself:

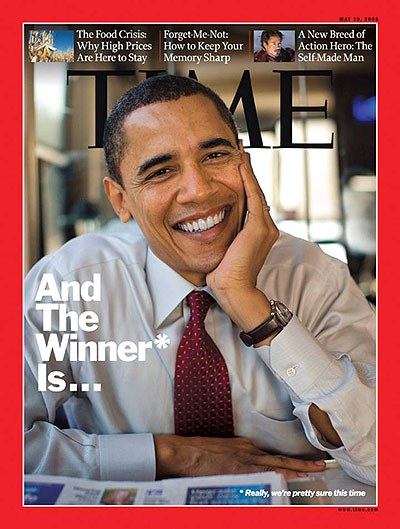

Hillary Clinton is not going to bow out of the race for the Democratic Presidential nomination until they carry her kicking and screaming from the convention hall in Denver after the last vote has been recorded.

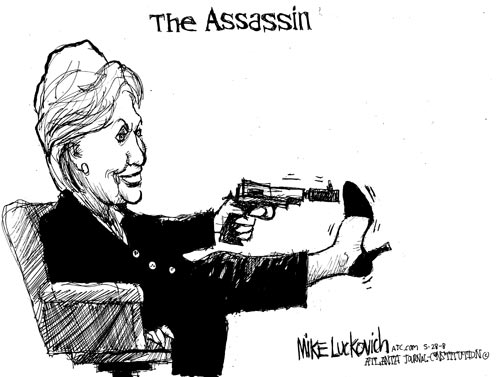

John Stewart may have put it best when he called the Clintons “simple people who want but one thing — to live peacefully in a country they, themselves, run.” Hillary Clinton has already adopted a strategy of racial polarization in order to win the nomination, as scurrilous a bit of political calculation as American politics has ever seen. She has spoken three times publicly about the assassination of RFK as an example of how anything can happen in a Presidential race (wink, wink, nudge nudge) — which is way beyond scurrilous, verging into the realm of the frankly vile. If she weren't named Clinton and if she weren't a woman her political career would already be over. The idea that she cares about her legacy, or this country, much less the Democratic Party, is absurd on the face of it. If she can't secure the nomination this year she will have one and only one overriding goal — to see that Barack Obama loses the general election in November so she can run in 2012.

The Clintons live in a reality of their own invention, and so far they've managed to seduce millions of people into joining them there. If she makes enemies destroying Obama this year, well . . . there will be millions of new suckers out there in four years, and she'll deal with them when the time comes. She may be shooting herself in the foot, but she doesn't need two feet — she needs the Presidency, on any terms she can get it.

If I'm wrong, and she bows out gracefully next week and devotes herself to party unity, I'll apologize for the words above. But don't count on it.