The first panel from a Sunday page published in 1924 — successive panels to follow!

By the incomparable Winsor McCay.

The first panel from a Sunday page published in 1924 — successive panels to follow!

By the incomparable Winsor McCay.

Charles Walters was a dancer and choreographer at MGM until he got a shot at directing, courtesy of Arthur Freed, who also promoted the directing careers of Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen by more or less the same route. Walters directed a lot of very good musicals and one great one, Easter Parade. He wasn't a great visual stylist but most of his musicals have wonderful visual passages connected with the song and dance numbers — long takes with elegant camera moves or tracking shots that lend a special sort of excitement and beauty to the scenes.

Texas Canival, from 1951, is one of his lesser efforts. It was produced by Jack Cummings, who had a knack for deploying the first-rate talent at MGM for second-rate efforts. Texas Carnival has a lame script by Dorothy Kingsley and a program of pleasant but less-than-memorable songs with lyrics by Dorothy Fields and music by Harry Warren. Hermes Pan did the choreography, featuring some crackerjack dancing by Ann Miller. Esther Williams, Red Skelton and Howard Keel, the rest of the principal cast, are genial but bland. None of the above artists is at his or her best here.

But there's one sequence in the film that makes it worth watching — a kind of dream fantasy in which Keel sees Williams floating around his hotel room one night, after he's fallen in love with her. It's done with impeccable superimpositions of Williams filmed swimming underwater and the effect is magical.

Williams, as everyone including Louis B. Mayer liked to say, was a star wet but not a star dry. Wet, however, she was really something — an expert dancer in a very unusual medium, H²O. (She's pictured above in a scene from Ziegfeld Follies, directed by Vincente Minnelli.) Her balletic moves worked best when they were simple and languorous, emphasizing the slow-motion effect naturally imparted by movement underwater. Like over-cranking in the camera, underwater dancing allows one extra time to savor the grace of a dancer's body in movement.

When used for a lyrical, erotic mood, as Walters uses it in the hotel-room scene, it can be haunting, uncanny, sublime. The scene points up one of the virtues of the second-rate MGM musicals — they often deliver moments and images as memorable as the best ones in the first-rate musicals . . . just enough magic to signal that MGM really was a dream factory like no other.

This boring postcard is from a Flickr set by Funhouse, who always puts up wonderful images.

The boring postcards in the set are not really boring, they just record unexceptional things, things you wouldn't look at twice if you saw them in real life — so in a way they're the most interesting things you could possibly look at, because they're normally invisible, and thus magically exposed by having a frame put around them.

The photographs of William Eggleston work on this same principle.

© William Eggleston

Also, any view of a past place and time slowly accrues enchantment, to the degree that it records unrecoverable things. Atget's photographic views of Paris are more miraculous now than they were when he first made them because the Paris he recorded is gone.

The bridge in the fishing scene above reminds me of the bridge that went over to the barrier island in North Carolina where I spent my childhood summers. In childhood, bridges were never boring, especially when they took you to your grandmother's beach house. To see any bridge, and especially such a bridge, as boring is to confront the general suppression of wonder that's part of the process of “growing up”.

Art like Eggleston's, and boring postcards like the one above, are bridges back to wonderland.

Here's Cory Doctorow, of Boing Boing, on the future of movies, from a recent article at the Internet Evolution web site — an article which deals with the future of traditional media in general:

The specific, rarefied animal that is the gigantic film spectacle demands a technological reality that has ceased to exist– just enough technology to distribute the films everywhere, but not so much technology that the audience gets to overrule your distribution decisions.

So, we may be at the end of the period in cinematic history where we can convince investors to pony up $300 million to make a sequel to a sequel to a remake of a movie adapted from a 50-year-old comic book. Which isn't to say that no one will make these things henceforth — give it a decade or two and there may well be rich weirdos who fund these productions the same way there are lovely old codgers who can be coaxed into putting up the dough to mount 15-hour, all-singing, all-dancing Wagner operas. Not a mass medium, nowhere near as culturally relevant as BBMs are today, but still a going concern as a vanity/prestige form.

Doctorow is right on target here. Traditional films have taken their shape and much of their content from the nature of the way they're distributed. Movies in the corporate era have never reflected “what the public wants”, because those who control distribution can in many ways decide what people want — or rather what they will accept in the absence of an alternative. The end of Hollywood's domination of distribution portends a drastic and irreversible change in the shape and content of movies.

So what will that change be like? Doctorow imagines a fragmented audience for YouTube-type videos consumed on computers, most of which will be aimed at very small niche markets, some of which might be popular enough to attract advertising dollars.

I see something else quite different happening — as a result of the confluence of the digital distribution of films to theaters and the desire, which is never going to going away, to experience dramatic works in a public setting, in the physical presence of other people, of strangers.

When all films are sent to theaters digitally, extraordinary possibilities will open up. The low cost of such distribution will, like the Internet, make it feasible for theaters, just like YouTube, to serve niche markets — at off-peak times, for example. Today, theaters make most of their money from concessions — they exist primarily to sell popcorn and candy and soft drinks. Any film that moves people past the concession stand can be profitable, as long as renting it is logistically simple and relatively inexpensive and as long as there is a way to advertise it cheaply.

What this will require, then, is some sort of interface between peer-to-peer-based Internet advertising and theater scheduling. Theater programming could be bottom-up — a local group with shared interests could “order up” a film screening by offering to fill a certain number of seats for it, perhaps reserved (provisionally) in advance by a click on a PayPal button. Another click on a computer-screen button in a theater manager's office could speed the film, whatever it happened to be, to the theater's digital projector at the appointed time.

The movie theater of the future could be simultaneously a venue for the latest Hollywood blockbuster, an art house, a local filmmakers festival, a clubhouse for hobbyists who like movies featuring trains, a Sunday-school classroom for people who want to see movies with religious themes. There's no way of predicting what audiences might really want to see. When Netflix started up, its directors assumed that most people would only want to see new movies — in fact, the vast majority of its rentals are for older films. Netflix created a bottom-up market which allowed consumers to express a preference no one could have anticipated.

A bottom-up market for theatrical films would allow new local communities to form, as they do virtually in cyberspace. A critical element in such a process would be a physical space within or near a theater where audiences for particular films or types of films could meet up before and after screenings. Such communities would grow exponentially and unpredictably, as they do in cyberspace.

It has often been suggested that virtual communities are filling a vacuum created by the disappearance of more traditional real-life community hubs — the neighborhood tavern (banished from suburban housing developments), the soda fountain, the diner, the church social. Virtual community can never truly replace such things, however — people are still hungry for the sort of “action” that only comes from physical proximity to fellow members of their species. This is one reason that teenagers still hang out in the soulless spaces of the mall, that people still want to go to the movies, even if there's nothing playing at the local multiplex that they really want to see.

The next step is only logical — apply the paradigm and the technology of virtual communities to create new real-life communities. Can it work? Ask Barack Obama.

I started my connection to the Obama campaign virtually, by sending in a small contribution online. I ended up on election day driving strangers from my neighborhood to the polls — one of the great experiences of my life. The transition was organic and easy — because it made sense, practically and emotionally.

The movie theater of the future will evolve in the same organic way and in retrospect will seem inevitable, as Obama's victory is already starting to seem inevitable. Meanwhile we just have to wait for the entertainment entrepreneur who can see now, as Obama saw in the political realm, which way the twig is bent.

A friend once asked the physicist Niels Bohr why he had a horseshoe over the entrance to

his house, for luck, since it was an example of a superstition, and he

didn't believe in superstitions. “I have it there,” said Bohr,

“because I was told it works even if you don't believe in it.”

Bohr did pioneering work on the structure of the atom and also conceived the principle of complementarity, the idea that items could be analyzed separately as having several contradictory properties . . . that light, for example, could be both a wave and a stream of particles simultaneously.

This idea has obvious spiritual implications, as the anecdote above suggests.

Richard “Wendell” Cordtz died last year. He was only in his fifties, about my age, so it came as a shock and still seems very strange.

He was one of the genuine characters I knew in New York for most of the years I lived there — an actor and stage director and singer. I didn't know him well but I saw him fairly regularly because he did a cabaret act with another friend of mine, Hugh McCarten. They billed themselves as Dr. Wendell and Mr. Hugh, Hugh providing piano accompaniment to Wendell's song styling.

Wendell had a wry and often very subtle sense of humor, characterized by a kind of sly irony hinting at the outrageous and delivered deadpan. It was a kind of mask, which would fall away when he smiled his sweet smile and suddenly seemed like a child. He was always very mysterious to me.

When musician friends visited from out of town there would sometimes be musical soirées at Wendell's loft. The last time I saw him was at one of these, not long before I moved away from New York. He sang a song I always associated with him, “Skylark” by Johnny Mercer and Hoagy Carmichael. He sang it beautifully, without any irony at all.

I have a recording of Dr. Wendell and Mr. Hugh performing the song, about a year before Wendell died. Listening to it it's impossible to imagine that Wendell is dead — easy to imagine that he's just gone off to follow the skylark somewhere . . .

Jack Cummings was MGM's third-string producer of musicals from the late Thirties to the mid Fifties (after Arthur Freed and Joe Pasternak.) He was unimaginative but reliable, able to churn out respectable product with occasional passages of sublime magic. One such bit of product from 1939 was Honolulu, an Eleanor Powell vehicle.

The film has an amiable but uninspired sit-com plot, centering on a Hawaiian pineapple grower and a big movie star who look exactly alike and decide, for various preposterous reasons, to switch places for a few weeks. Robert Young plays the dual role. As the movie star seeking a respite from hysterical fans he falls in love with Powell, a dancer with a gig at a Honolulu night spot.

In the dialogue scenes, Powell is every bit as bland and pleasant as Young — they're acceptable company for a bit of romantic comedy fluff. So far so good. When the Hawaiian drums start to throb, however, and Powell starts dancing, she sizzles with an intense sexuality that leaves Young wailing on the margin of non-entity, both dramatically and as a cinematic presence. After Powell's first big number, the film no longer makes any sense as a love story.

Powell's three big numbers in the film, all solos, two with a corps of other dancers behind her, are stunning, though — they make the film worth watching, and revisiting. In the first, she partners with a jump-rope, and makes it look sexier than Young. In the last she does a fierce hula in a grass skirt, first barefoot then in tap shoes. It has to be seen to be believed — her hip movements are simply indecent.

Another of the film's delights is Gracie Allen, who plays Powell's partner in her nightclub act. She flits in and out of the plot delivering some first-rate vaudeville gags with her usual brilliance. If you think of Honolulu as a program of vaudeville turns, rather than as a book musical, it's much easier to enjoy. Powell, like Allen, was a product of the variety stage, so it's really not that much of a leap. (George Burns is also in the film, but has no scenes with Allen, and flounders a bit with the less-than-amusing material he has to work with here.)

The film has some problematic racial stereotypes. Eddie Anderson is made to do a gibbering “I'se just seen a ghost!” turn, which is doubly offensive because it clashes so markedly with Anderson's wry and skeptical comic persona, which Jack Benny exploited so well in his radio and TV shows. Using Anderson as he's used in Honolulu is just an example of the mindless demeaning of blacks. Willie Fung does a more amusing stock Chinaman turn, in which he gets to engage in a bit of one-upsmanship over his patronizing boss.

Then there's Powell's blackface number, in which she dances an imitation of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. This cannot be simply dismissed, however disturbing the very idea of blackface has become. There is no trace of condescension in Powell's tribute to Robinson — it's more an act of admiration, even envy. Powell took lessons from the great black tapper and she imitates him convincingly — though her version of his tapping up and down stairs is just a faint echo of Robinson's signature routine. She would probably have enjoyed dancing a romantic tapping pas de deux with Robinson — he's one of the few dancers who could have held his own with her, and then some — but that would have been inconceivable in 1939, probably even in 1969 in any mainstream showcase.

So Powell became Robinson for a few minutes. It's hard to see the impersonation as anything but an act of tenderness and love.

The film was directed by journeyman Edward Buzzell. Bobby Connelly did the simple but effective choreography — he did the simple but effective choreography for The Wizard Of Oz that same year. Sadly, Honolulu is not yet available on DVD, though it's shown from time to time on TCM.

There had never been anyone quite like Annie Oakley and there will never be anyone quite like her again, because no American girl will ever again have to travel the path Oakley negotiated between female respectability and female empowerment. Oakley dominated the traditionally male arena of target shooting but said her highest aim in life was to be thought of as a “lady” — as having transcended a childhood of desperate poverty and abuse, risen from the ranks of “white trash” to hob-nob with presidents and kings and queens.

Her act, as both a performer and a woman, was finely calculated. She supported equal pay for equal work by women and believed that all women who could should learn to handle firearms, for self-protection and healthful exercise, but would not endorse women’s suffrage — that, she felt, would take her one step beyond the limits of female Victorian propriety.

She always performed fully covered from head to toe, with leggings that hid even her ankles, but also with her long hair unbound — a daring style in her time, which she got away with by adopting a childlike deportment that made the long hair seem less brazen (but still sexy.) She never apologized for beating men at their own game but never gloated over it either. In almost all the fictional accounts of her life she is shown deliberately missing a shot to sooth the ego of a male competitor but the real Annie Oakley would never have done such a thing — she would certainly have seen it as demeaning, both to herself and to her competitor.

She pulled no punches and gave no quarter when she had a gun in her hands, but was always gracious in victory. That’s what being a lady meant to her.

She shot, unusually, with both eyes open, and she examined the world she lived in with both eyes open, too. You can get a sense of the clarity of her vision in the portrait above — I imagine she could make an insecure male feel like a live pigeon just released from the trap as she drew a bead on it.

I can't exactly recommend this book, because it's so grim and harrowing, but I can report that it's one of the most important books ever written about the Civil War, and about war in general. It takes a frank and even brutal look at the phenomenon of mass death on American soil between 1861 and 1865, and allows you to get in touch, at least partially, with the unspeakable horror of it. It's certainly an indispensable book for anyone, like myself, who's ever been infected with the “romance” of the Civil War, or of war in general.

About 600,000 soldiers died in the Civil War, plus an uncounted and today uncountable number of civilians. As a percentage of the U. S. population now that would work out to over 2,000,000 people. Faust does her best to give us a sense of how the survivors tried to cope with this ghastly slaughter — emotionally, spiritually, politically, philosophically and physically. It was an epic endeavor. On the most basic level, the physical, no one was prepared for the task of disposing of so many tons of rotting meat that had once been human beings. On a higher level, there were no rituals of mourning in place for loved ones who died so far from home, often suddenly, without warning, and so conceivably “unprepared” to meet their Maker, and whose bodies in tens of thousands of cases remained unidentified and unrecoverable.

Faust, for once, deals equally with the mechanics of death and with its lasting consequences for those survivors who had to manage its effect on their own lives.

The Civil War dead cast long shadows, and we stand among those shadows today, whether we know it or not.

The instinctive is what counts in a

story. What the writer wants to say is the least important thing; the

most important is said through him or in spite of him.

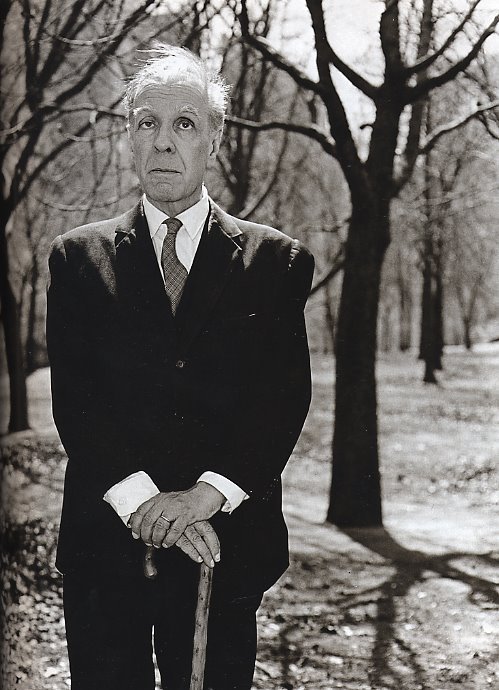

[Portrait of Borges by Diane Arbus.]