On you it looks good . . .

[Al Moore for Esquire, 1950.]

On you it looks good . . .

[Al Moore for Esquire, 1950.]

The adventure continues — into and out of the Dragon Lady's clutches . . . but for how long?

Caniff is great at setting up action sequences with static, tableau-like panels. Also, check out the dynamic cut between the fourth-from-last panel and the third-from-last panel — the socked pirates flies left, Terry and Pat jump right. For a subtler effect, notice the slight change of expression on the Dragon Lady's face between the next-to-last panel and the “cut-in” to the last panel, giving the impression that you've actually seen her lips move . . . just a bit.

Hell’s Angels

went into production in the silent era. While it was being filmed

the craze for sound erupted and producer Howard Hughes reshot most of

it as a talkie. This resulted in a film that cost nearly four

million dollars and took almost three years to complete.

Along the way Hughes lost his first director, Marshall Neilan, and took

the reins himself, bringing in James Whale, fresh from the English

theater, to “stage” the dialogue scenes.

The result is a mess, but also one of the God-damnedest entertainments

ever concocted in Hollywood — an absolutely fascinating folly.

The film is made up of four poorly integrated elements:

1) A creaky melodrama about two brothers involved with the same women

who end up serving together in the Royal Flying Corps in WWI.

2) A showcase for the miraculous cinematic presence of an 18 year-old Jean Harlow.

3) An extended sequence about a Zeppelin raid on London with stunning miniatures and special effects.

4) A twenty-minute episode of ariel combat shot in and from real planes that has to be seen to be believed.

The inadequacy of element 1) is what makes the film a bit of a chore to

sit through, though the other three elements make the effort intensely

rewarding at times.

Harlow doesn’t have much of a role and

doesn’t really act it — but she’s such a natural screen performer that

you simply don’t care. Watching her have her being in front of a

camera is as thrilling as watching the mind-boggling stunts of the

flyers at the end of the film.

The Zeppelin raid seems to belong to another film entirely — it has a

spooky, morbid tone and an expressionistic visual style that hark back

to the great UFA films of the 1920s. It’s extremely beautiful and

haunting but has no organic connection to the film’s narrative.

The twenty-minutes of ariel combat must rank among the highest

achievements in all of cinema. The lead actors in the film appear

in actual planes that are actually flying. Flyers in other planes

act out moments of the airborne drama. A complex ariel battle

unfolds lyrically and logically before our eyes — almost all of it

done for real.

Three flyers were killed during the production — only one of them,

though, during actual shooting, in a stunt gone wrong. The

dangers all the flyers risked is there on the screen at every moment,

however, and the result is truly breathtaking.

It’s sad that these twenty minutes of cinematic bravura don’t provide

the climax to a great film, or even a very good film, but they will

always constitute one of the great legacies of the movies . . . and of

a sort we will probably never see again. Martin Scorsese

recreated the filming of Hell’s Angels in his biopic of Hughes, The Aviator, using CGI. Compared to Hughes’s folly Scorsese’s homage is a big yawn.

Mayor Oscar Goodman, sitting in a smoke-free poker bar surrounded by scores of new Las Vegas residents, all recently arrived from California, announced that the city would adopt “Viva Viagra”, a version of the Elvis classic “Viva Las Vegas” with new lyrics, as the city's official song. “Were sending a message,” he said, “that Las Vegas is no longer a frontier town — it's a place where limp dicks everywhere can feel right at home.”

He also said that plans were afoot to introduce a new slogan for the city's tourism advertisements — “What happens in Orange County happens in Vegas!” He added that this slogan had narrowly beaten out a competing ad line — “Go gay . . . the hetero way!”

“Things have changed here,” said Goodman. “We're not an outlaw outpost anymore — we're California with sequins! What could be more fun than that?”

The cinematographer and sometime director Jack Cardiff has died. He helped create some of the most sublime images in the history of movies. Above, one of those images — from The Red Shoes.

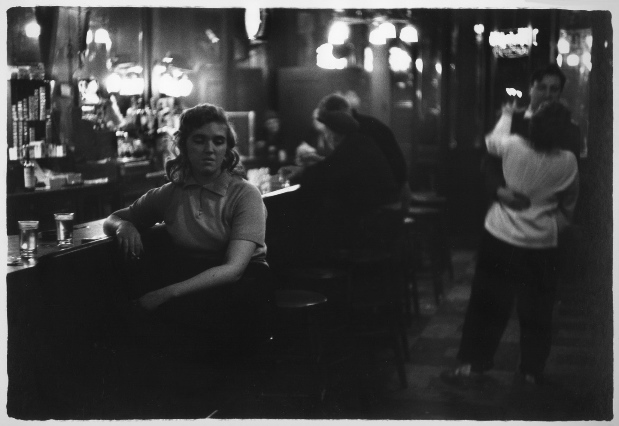

[William Gedney]

What with one thing or another I'm sure many of us never made it to church this past Easter. My own personal feeling about attending church is exactly that of Madea, a recurring character in the films of Tyler Perry, who says she'll go to church when they put in a smoking section. Madea and I, both smokers, are not holding our breath — what's left of it.

Some of us may be wondering what we missed by failing to attend church on Easter, but we need wonder no longer. Click here to listen to an actual sermon preached by my friend PZ this past Easter at a church in the Washington, D. C. area. It's the real deal — no pussyfooting around. He speaks of the Resurrection as a literal, historical event, and he speaks of Heaven as a real place.

It's not for the faint of heart.

But listen to the ideas behind the images, listen to the psychology of it. It's not as crazy as it seems — or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that its very craziness is invested with some serious counter-intuitive wisdom.

[William Gedney]

Consider the Heaven that Dr. Z speaks of, where we will meet those who hurt and wounded us in this life, but meet them transfigured by Grace into the people we wanted and needed them to be. Consider the very notion of Heaven, which must by definition be wholly transcendent and eternal — which must be outside of time . . . must be indeed a rebuke to time, a negation of time. In short, if we're going to Heaven, we're already there . . . always have been, always will be. Heaven, destroyer of time, cannot be a future eventuality.

Jesus said, “The kingdom of God is at hand” — not “coming soon to a theater near you”, but here . . . as close as your outstretched fingers. He said, “The kingdom of God is within you.” All of Buddhism is a meditation on this idea. Eastern spiritual traditions have always been more eloquent on this aspect of Jesus's teaching than Western institutionalized Christianity.

There have been some exceptions to this rule in the Western Christian tradition. Kierkegaard said, “Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards.” Isn't “Heaven” just a way of imagining life backwards — making sense of it retrospectively while we're in the midst of its chaotic nonsense?

[William Gedney]

The peroration of Dr. Z's Easter sermon is borrowed from Bob Dylan:

The cards are no good that you're holding,

Unless they're from another world.

All questions of theology aside, this is a difficult proposition to refute from actual life experience . . . yours, mine, anybody's.

The temperatures are inching up into the 90s out here in the Mojave Desert, a harbinger of the furnace-like heat that's on its way . . . making it a good time to pause and contemplate a Currier & Ives winter scene.

Orson Welles was clearly trying to evoke Victorian prints like this in the sleigh-versus-automobile episode in The Magnificent Ambersons. He may even have had this particular print in mind, with its rider tumbling from the overturned sleigh and the snowy road winding off into the distance under the bare tree branches.

Recently, watching an excellent documentary about Buffalo Bill Cody, from the PBS American Experience series, an image jumped out at me. It was part of the relatively rare surviving film depicting Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show in performance. It depicted one of the show’s most popular episodes — “The Attack On the Settler’s Cabin”. A fairly small, square replica of a cabin was set up in the middle of the arena. Performers portraying a pioneer family would defend this from an attack by mounted Indians until Buffalo Bill and his trusty cowboy compadres rode in to rescue them. (The photograph of the cabin above gives a sense of its stage-set quality but not of its isolation in the emptied arena, conveyed in the documentary film footage.)

The precise iconography of the image, and not just the dramatic situation, seemed oddly familiar, and I quickly realized where I had seen it before — in the films of D. W. Griffith. Several times — in The Battle At Elderbush Gulch and in The Birth Of A Nation, for example — Griffith had staged an attack on an isolated cabin that evoked the staging in Buffalo Bill’s arena. Griffith would start with a long shot of a small, square cabin in a valley that had the theatrical quality of an arena. He would cut back repeatedly to this long shot during the course of the attack.

Of course, an attack on an isolated cabin would become a staple of Western films, as would most of the episodes of Buffalo Bill’s show — the attack on the wagon train, the ambush of the Deadwood Stage, the heroics of the Pony Express Rider, the buffalo hunt, Custer’s (or some other cavalry leader’s) last stand against swarming Indians — but Griffith’s iconography was very distinctive and rarely reproduced, the cabin looking too small to hold the defenders later revealed to be inside it, set in the middle of a topographical amphitheater, seen from above, as though from some ideal vantage in the bleachers.

Note also (in the frame above from The Battle At Elderbush Gulch) the curious isolation of the cabin, with none of the outbuildings or stock pens one would expect to see surrounding a real pioneer home. The cabin has something of the feel of a set, or a prop, as did Bill’s cabin. Contrast this with the remote homestead attacked by Indians in The Searchers, which looks like a working ranch complex.

I’m sure that Griffith was echoing, consciously or unconsciously, something he’d witnessed in a performance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West — augmenting the theatrical spectacle with the photographic authority of a movie shot on a real location. The reality of the location was important — it was part of what made all Wild West arena-show recreations seem old-fashioned to the growing audience of 20th-Century moviegoers — but the evocation of Buffalo Bill’s show was also important, because this was where so many moviegoers had gotten their first thrilling glimpse of the mythic West that Bill had done so much to create or consolidate in the world’s imagination.

This is a painting of Marcelle Lender dancing a bolero in an 1895 revival of Hervé's Chilpéric, an opera bouffe from 1868.

You could make a case that Kern and Hammerstein's theatrical adaptation of Show Boat has been given too much credit for its influence on the form of the American musical and not enough credit for its contribution to the American dialogue about race.

If you think about it, the so-called “integrated book musical”, with songs that arose naturally out of the story and served to advance the drama and delineate character, already existed on the world's stages in the form of operettas. Operettas in the early 20th Century were often semi-serious, romantic dramas — not all that different from Show Boat — and by the time Hammerstein wrote the book and lyrics for Show Boat he had already written the books and lyrics for several operettas. Kern had gotten his start in theater supplying additional songs for Continental operettas in their British and American incarnations.

The radical innovations of Show Boat were not so much formal as tonal and stylistic. It eschewed the European atmosphere of traditional operettas and their farce-like plots, often involving a romance between two people who belong (or more commonly think they belong) to different classes. And it added to the operatic style of music evoked in operettas distinctly American strains, derived from an African-American musical tradition.

More than this, it created a kind of dialogue between the European operatic tradition and the African-American musical tradition — a dialogue which is incorporated into the interactions between black and white characters in the story itself. The African-American music used in the play is pre-ragtime, pre-jazz, although those innovations are alluded to in the play's concluding scenes. Mostly, however, Kern's score deals with spirituals and the kind of lightly syncopated music associated with the minstrel stage — the cakewalk and the shuffle.

The African strain, of course, is what makes American music American. It's the American quality of the Show Boat score that makes it so distinctive, so unlike anything which had gone before — and it's the explicit recognition and dramatization of the African cultural influence that makes Show Boat such a resonant meditation on American culture.

When the curtain opened at he premiere of the show in 1927, the first word that came from the stage was “Niggers”. It came from the mouths of black laborers loading cargo onto boats at the dock where the Cotton Blossom Floating Palace Theater was tied up. “Niggers all work on the Mississippi,” they sang. “Niggers all work while the white folks play.” That first-night audience saw the white folks' playhouse, the show boat, where blacks couldn't play — a fact soon to be made explicit in the text when a member of the Cotton Blossom troupe (Julie LaVerne, played by Helen Morgan, above, in the stage production and in the 1936 film) is exposed as a woman of mixed race and expelled from the show boat community. All the while, the music of black America pervades the playhouse, shapes the entertainment offered there.

This was bold stuff in 1927, and when Show Boat became a beloved American classic, even Hammerstein retreated from it. In subsequent revivals, the word “nigger” was done away with. The first line of “Ole Man River” was changed to “Darkies all work on the Mississippi” and then to “Colored folks work on the Mississippi” and then to “Here we all work on the Mississippi”.

Something of the deep and transgressive irony of Hammerstein's original inspiration was lost in the process — just as something of Twain's deep and transgressive irony in Huckleberry Finn would be lost if the word “nigger” were to be removed from that book. Certainly removing it from Show Boat makes us feel better — but it was there precisely to make us feel uneasy.

The troublesome themes of Show Boat remain, however, even when its language is prettied up — and its themes, far more than its supposed formal innovations, are what make it perennially radical and important.

“I want to know what it says, the sea. What it is that it keeps on

saying.”

— from Dombey and Son:

If you lean in close, so I can whisper in your ear, I'll tell you . . .

Love lasts forever

Love never lasts

Love lasts forever

Love never lasts

Love lasts forever

Love never lasts

Love lasts forever

Love never lasts

Hush

Hush

Hush

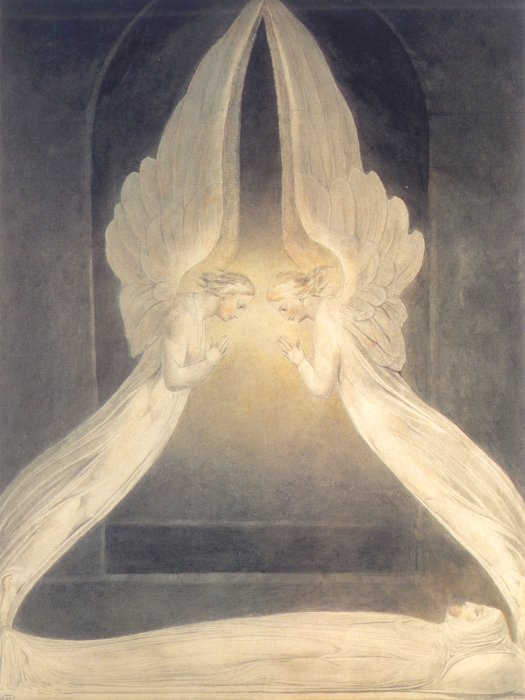

“What,” it will be Question'd, “When the Sun rises, do you not see a

round disk of fire somewhat like a Guinea?” Oh no, no, I see an

Innumerable company of the Heavenly host crying, 'Holy, Holy, Holy, is

the Lord God Almighty.'

— William Blake

[William Gedney]

. . . every day see one more card.

You take it on faith, you take it to the heart.

The waiting is the hardest part.

— Tom Petty

. . . you find out you can always lose a little more.

— Bob Dylan

[These thoughts on Murnau's The Last Laugh contain plot spoilers — don't read them unless you've seen the film . . . instead, go see the film, one of the greatest ever made.]

The original German title of Murnau's masterpiece The Last Laugh was Der Letzte Mann, “the last man”. In English this phrase can have a positive connotation, something like “the last real man”, or “the last man standing”, but in German it only connotes degree or place in a literal sense — something like “the lowest man”, “the least of men”, “the last man in the pecking order”.

In the film, the title is explicitly but somewhat ironically linked to the Biblical phrase “the last shall be first, and the first last“. This saying of Jesus appears four times in the New Testament but only in the Synoptic Gospels (i. e. not in John) and in a couple of different contexts. The phrase is often read as simply contrasting the rich and powerful with the poor and oppressed, who will somehow triumph in the fullness of God's justice, but this is a misinterpretation in at least two cases. In those passages, “the first” Jesus refers to are his own self-righteous followers who feel they have some special connection to him and to God because of an imagined advantage they possess — either from having “seen the light” before others, or having spent more “quality time” with him.

Jesus is making the point in those cases that status in some imaginary “Jesus club” has nothing to do with true righteousness, as judged by God. He is offering a rebuke not to those with power who oppress believers but to believers who lord it over their fellow believers. This is obviously not a congenial message to the organizers of religious institutions, for whom sanctioned membership in the official “Jesus club”, with attendant privileges, including eternal salvation unavailable to others, is a prime selling point and recruiting tool.

Jesus's phrase is obviously deeply ironic, and it is introduced ironically in Der Letzte Mann. It appears in the very odd epilogue to the film — the preposterous reversal of fortune in which the doorman demoted to restroom attendant receives an unexpected inheritance and suddenly becomes a man of wealth and privilege, elevated even above the position whose loss had crushed him earlier.

This epilogue follows the film's only intertitle, which is interjected after the washroom attendant has reached the depths of defeat and despair. The intertitle is unrelated to the narrative proper and represents the filmmaker addressing the audience directly and commenting on the narrative. He says that the defeat of the protagonist is how such stories end in real life but that he (the filmmaker) is not content to leave the matter there and will instead, out of love for the protagonist, supply his story with a happy ending.

This is, to put it mildly, disorienting. We're being told, in effect, that the happy ending we're about to see is a fraud, or a fantasy — and that's exactly how it plays. The new dream life of the protagonist is exaggerated and surreal, moving beyond the precincts of expressionism into the realm of the purely fantastic. The protagonist doesn't just enjoy a fancy meal, he stuffs himself from a dessert concoction the size of a small building. He doesn't just serve caviar to his best friend, he shovels gobs of it from a vast pot onto his friend's plate. The whole things seems to be an insolent challenge to the audience, asking, “Do you buy this?”, “Is this what you wanted to see?”

The first shot of the epilogue shows a group of silly-looking rich folk reading a newspaper account of the protagonist's reversal of fortune and laughing derisively — as though they know how ridiculous it is. It's hard not to see these people as Murnau's image of us, of the audience, cynically demanding happy endings for “the least of men” all the while knowing that happy endings are only for the privileged, for the self-styled “first” of men. Exceptions to this rule are the stuff of comedy, of satire or farce.

Murnau shows us the newspaper account the rich folks are laughing at, and it's this account, ironic and unserious, which quotes Jesus's saying, rather frivolously — “It looks as though the old Biblical saying is being fulfilled, that 'the last shall be first'”. Then we are shown the rich folks laughing even louder.

Murnau was apparently forced to add the happy ending to the film, but he subverts it mercilessly, suggesting that Jesus's observation about the first and last is just a joke to most people, something that only applies to the dreamworld of popular entertainment. It's hard to imagine Jesus disagreeing with him.

In a film about the making of Der Letzte Mann included on the new Kino DVD edition of the restored film, it is suggested that the story is an anti-militaristic fable — the doorman's obsession with his uniform as a status symbol being a metaphor for German society's obsession with military adventurism. This of course casts Murnau in the best possible light as a “good German” — going against the grain that led Germany to start the Second World War. Murnau and his screenwriter Carl Mayer may have had some such criticism of Germany in mind, but it's hardly the heart of the film — which I think is much closer to the Biblical text they reference in their story's title and in the newspaper article their rich folks find so hilarious.

This is not to say that Murnau and Mayer (a Jew) meant their film to be interpreted from a “Christian” perspective, but it seems inescapable to me that they were using a Christian image — die Letzten, as Luther translated the Greek of the New Testament, εσχατοι, “the last men” — to express their deep love of one beaten and defeated man, and their anguish over his oppression by a cynical and arrogant and hypocritical society, a “Christian” society.

Interestingly, and tragically, Carl Mayer died a “last man”. Like many Jews in the film industry he fled Nazi Germany and ended up in England, where he had trouble finding work. He developed cancer, which was apparently poorly treated, due to to wartime strains on medical facilities, and died with 23 pounds and two books to his name. I'd love to know what those two books were.

I must add that the recent restoration on the Kino DVD is miraculous. The film was shot to produce three negatives, one for German release, one for American release and one for general international release elsewhere. The footage for the German release is far superior in terms of framing and action and has been reconstructed from a variety of sources for the version found on the new Kino edition. The quality and beauty of it are really breathtaking. This is probably the best version of the film ever available to American viewers in any form.