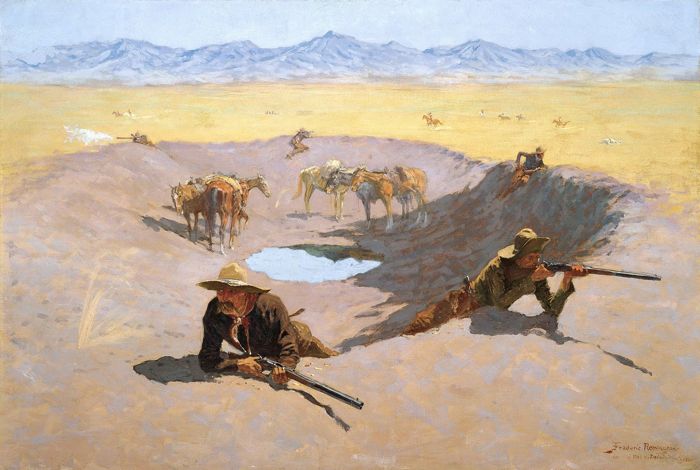

The unmanned drones being used against targets in Pakistan today are controlled from Creech Air Force Base in Nevada (above), about fifty miles from Nellis Air Force Base — just north of Las Vegas, where I live. This is very surreal, but is it also immoral? Paul Zahl offers some thoughts on the subject:

IS ANYBODY OUT THERE?

a now almost canonized but then extremely unpopular speech in the House

of Lords, Bell challenged the Government on its bombing policy. In the play Soldiers Hochhuth imagines a personal meeting between Winston Churchill and Bishop Bell, in which they debate the morality of bombing from the air, especially when there is the possibility, even the probability, of civilian deaths.

Churchill believed that the bombing of civilian centers was essential to the Allies' winning the war. Bell believed it was a war crime.

Here are a few lines that the playwright puts in the mouth of Bishop Bell. They are mostly lifted from Bell's speeches and writings, or deduced from them:

Stage Direction:

“BELL, by his quiet strength, has released something akin to shame in CHURCHILL. This cannot be indicated logically, only portrayed illogically. The feeling does not last. The PRIME MINISTER is discomposed for a moment by the knowledge that someone is stronger than he is.”

Bell is a saint, in memory, of the Church of England. Then, he was a

pariah. Dresden was still bombed. The Atom Bomb was dropped, twice. [Below, the aftermath of Dresden:]

about combatants who cannot see, for a distance not of 30,000 feet,

but of 10,000 miles, the enemy, let alone the enemy's family, who are

burned in an instant to a cinder?

What would the hero of Hochhuth's Soldiers think about what we are doing today?