My friend Jae's cell phone can take panoramic pictures, like the one above of myself and our pal John hanging out at a bar in the Venetian, resting up from a grueling poker session.

Monthly Archives: December 2008

SUNRISE RECONSIDERED

[Warning: If you haven't seen Sunrise, don't read this — instead go

see Sunrise immediately.]

Sunrise may not be the greatest film ever made — it may not even be

the greatest film of the silent era — but it certainly has passages,

many passages, that rank among the greatest in the history cinema and

still help chart the limits of what the medium can do.

Oddly, though, most of these supremely great passages happen in the

first 45 minutes of the film. After that, there are many wonderful

moments, much gorgeous lighting and many striking plastic effects, but

none of them are breathtaking in the way the high points of the first

half are.

I think there's a fairly simple explanation for this, and it has to do

with the structure of the story itself. The film tells the tale of a

simple man living in a rustic farming and fishing village who's seduced

away from his wife by a vamp visiting the village from the city. He

determines to drown his wife in the course of a boat outing but when he

moves to do so he sees himself, sees what he's become, in her terrified

eyes and draws back from the deed. She flees him when they get to land

again, jumps on a trolley — he jumps on, too, and they ride into the

city. There, as he's trying to atone for his awful behavior, they

stumble on a wedding. The man falls apart, begs for forgiveness, is

forgiven, and they walk out of the church like a newly married couple.

This is the artistic, emotional and spiritual climax of the film . . .

but the film is only half over.

We then see the couple recover their former lightheartedness at a

fairgrounds. We cut back to the scheming vamp in the village, and this

sets up an expectation that she will somehow intervene in the couple's

reunion and jeopardize it — but in fact this never happens. The man

has made his choice — the vamp has no more power over him.

On the boat ride home a storm washes the couple overboard, the man

thinks his wife has drowned, and he's devastated. There's great irony

in this, of course, but no great dramatic weight, because it doesn't

involve any further development of the characters' inner lives. The

storm is a mechanical contrivance — an impersonal threat to a marriage

that has already been reborn and renewed.

The man rejects the vamp with physical violence, almost killing her,

before being told that his wife has been found alive — saved by a

bundle of reeds the vamp had gathered as a device for the man to use to save

himself after he'd killed the wife. Again, there are multiple

ironies in these developments but, again, no real progression in the

inner lives of the characters. The storm isn't a direct consequence of

the man's past behavior and the reeds don't redeem the vamp — they are

like visual and narrative puns with no fundamental significance for the

basic drama.

The second half of the film does contains things one would miss if Sunrise had ended at the halfway point. In the fairgrounds

carousing, Janet Gaynor's character gets to reveal herself as a sensual

being, something she isn't really able to do as the long-suffering wife

in the opening sequences, where her astonishingly bad helmet-wig seems

to be giving her a headache — as it gives us one. The George O'Brien

character is so frankly sensual, even when he's menacing, that there

would be an imbalance without those fairgrounds scenes. O'Brien's

character also suffers in the second half from the apparent loss of his

wife, a tragedy he almost brought upon himself. Without seeing that

suffering, we might feel that he'd gotten off too easily for his

despicable behavior. And of course the vamp gets her comeuppance —

though it's almost more comeuppance than she deserves.

But none of these things transcends the emotional and dramatic climax

of the scene in the church or adds anything of essential significance

to it. They're like echoes of and reflections on a story that's

already been told. In the second half, Murnau can't summon up sublime

cinematic expressions for powerful emotional developments — because

those developments simply aren't there.

Pointing out the flaws in the dramatic structure of Sunrise does

nothing, of course, to diminish its stature as one of the most

important works in the history of cinema. It was the film that taught

John Ford the secret of movies, and that alone would make it a work of

inestimable value. It's one of those rare films that one one can watch

again and again with increasing astonishment and enchantment, and it

continues to inspire each new generation of filmmakers, especially

cinematographers, for whom it is a kind of touchstone. But recognizing

its structural flaws might help explain the vague and perhaps even

guilty feeling of disappointment which steals over one whenever that

“Finis” card comes up on the screen.

The great passages of the film, great as they are, don't add up to a

great whole work.

[Vincente Minnelli's fine film The Clock has a couple of intriguing echoes of Sunrise, which I think are too close to be accidental. Both films deal with moments of crisis in a marriage that play out in an urban setting. In both movies, the crisis is at first exacerbated and then transcended by the city environment, which becomes a kind of character in the drama. In the aftermath of both crises, the married couples try to get back to a state of normality in a restaurant, but the simple act of trying to share a meal only emphasizes the distance between them. In both restaurant scenes, the women break down. These scenes are followed by ones in which the couples happen upon a wedding in a church — they enter the church and participate vicariously in the ceremony, which restores their sense of commitment to each other. In each film, the church scene is the emotional climax of the story. In The Clock, the rest of the film is coda — in Sunrise the rest of the film is coda, too, but stretched out far too long, and too loaded with incident, to work properly as such.]

CHRISTMAS LONG AGO . . .

. . . but not that long ago — from a 1910 issue of St. Nicholas Magazine.

[With thanks to the ASIFA – Hollywood Animation Archive.]

PINTER

“Harold Pinter is dead.”

“His plays were hard to understand.”

“Yes, but he's dead.”

“The characters seemed like they came from different plays.”

“Cancer.”

“What?”

“He died of cancer.”

“Cancer?”

“Yes, it killed him.”

Pause.

“So . . . Harold Pinter is dead.”

“Dead as a doornail. Of cancer.”

“Ah.”

Long pause.

ABSURD

Two thousand years ago, in an obscure backwater of the Roman Empire, a child is born into the family of a modest artisan. He grows up to be a teacher of uncommon subtlety and wisdom, is executed for blasphemy and later worshiped widely across the globe as the Son Of God. His birth is celebrated at the Orleans Casino in Las Vegas with a special promotion entitled “The Twelve Days Of Cash-mas”.

Go figure.

AVE MARIA

Hail, Mary, full of grace — the Lord is with thee.

Blessed art thou among women

And blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus.

Holy Mary, Mother of God,

Pray for us sinners,

Now and in the hour of our death.

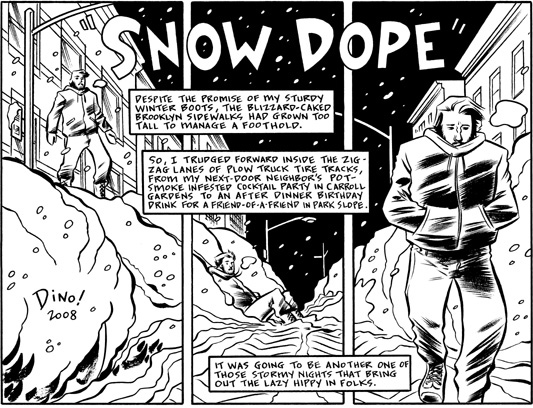

SNOW DOPE

Recently published on The New York Times's web site, Snow Dope by Dean Haspiel — a celebration of the consolations of urban solitude, snow and drunkenness. Read the rest of the short strip here. The spirit of Jack Kerouac lives — sad, mad and transcendent. Kerouac knew that the ghost of Walt Whitman walks with every lonely drunk down every lonely street and along the side of every lonely highway in America, and you can feel his presence in Haspiel's panels.

CHEERS FROM CARTOONLAND

A cartoon-moderny greeting from the Disney studio — the classic characters don't look quite right in the style, but we overlook that in the spirit of the season.

UNNERVING

Matt Barry over at The Art and Culture Of Movies has recently posted an insightful short review of Orson Welles's Touch Of Evil. He calls it an unnerving film, which it certainly is, but points out that one of its most unnerving aspects is the way Welles goofs on our expectations of what a gritty little film noir should be.

The film's extreme stylization both seduces us into its nightmare world and distances us from it as an aesthetic creation, all at the same time. Touch Of Evil was not quite the last classic noir — I think you'd have to give that distinction to Odds Against Tomorrow, which came out a bit later — but its self-consciousness about the form was a sure signal that the tradition had all but played itself out. One definition of a neo-noir is that it's at least as concerned with commenting on the form as with working inside it. In some ways, Touch Of Evil was the first of the neo-noirs.

HAVE A DOTY CHRISTMAS!

Some holiday cheer from Roy Doty . . .

SNOW!

[Image © 2008 John Gurzinski/Las Vegas Review Journal]

It snowed in Las Vegas yesterday — almost four inches of the stuff fell around the valley, much more in some places. It was the biggest snowfall since 1937, when records of such things started to be kept. McCarran Airport was shut down. Girls wearing Ugg boots, which usually seem so preposterous out here in the desert, were the only people prepared for the event.

Having worked all night and crashed in the morning, I slept through most of it, so it was surreal beyond words to wake up briefly in the late afternoon, wander into the kitchen for some water and peek out the window — the Strip was barely visible through the veil of white. I turned on the radio to confirm what my eyes had apparently seen — a snowstorm in Sin City. It felt very cozy to get back in bed and doze off again.

Before dawn now, as I write this, the snow has stopped but there are still patches of it on the ground, on the pine trees and the steps outside my apartment. A strange visitation.

HOLIDAY GREETINGS FROM HAROLD GRAY

Arf!

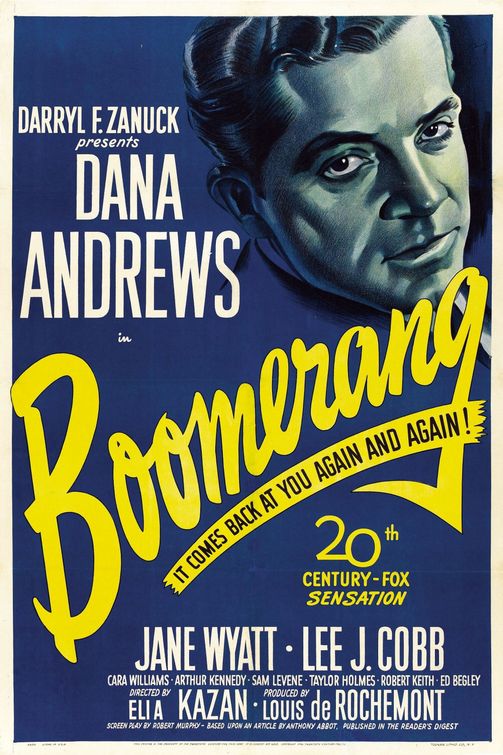

BOOMERANG!

Ivan Shreve over at the ever wise and amusing Thrilling Days Of Yesteryear writes, “The argument over whether or not Boomerang! is a legitimate film noir will rage on until eternity.” Of course it will. Arguments about what films are or are not noir are almost always irrational and thus can never be settled in any reasonable way.

The general idea is to parse any film made in Hollywood in the 1940s and 1950s searching for reasons to call it noir. The use of shadows, the element of crime in the plot, any suggestion of moral ambiguity or darkness in the characters is usually enough to qualify a film for the designation. The truth is that film noir is no longer a descriptive or analytic term but one of approbation — it means “a film which is cool, a film I like”. Sometimes it just means an old film in black-and-white which isn't a comedy or musical.

It would be far more logical to ask a simple question up front — is there some other established genre or tradition into which a particular film fits? If there is, there's no conceivable reason to tag it as a noir. Doing that just makes film noir a term so vague as to have no real meaning at all.

As it happens, Boomerang! fits nicely into a very distinct tradition usually called docu-noir. The tradition was virtually invented by Louis de Rochemont, who happens to be the producer of Boomerang! De Rochemont made his name producing the March Of Time newsreel series, essentially a breezier and more entertaining variant of the standard newsreel. He then became a producer of features at Fox. His first film, the docu-noir The House On 92nd Street, set the pattern for the new form.

Docu-noirs were police or government-agency (or sometimes newspaper) procedurals, usually based on real events and filmed in a quasi-documentary style, often in the locations where the real events occurred. Although they dealt with the same post-war anxieties that fueled the classic films noirs, they were radically different kinds of films, because they took the point of view of the authorities and they insisted that the official institutions of society could combat society's ills.

[Caution, plot spoilers ahead . . .]

The protagonist of a docu-noir might encounter corruption within the institution he served, but his personal integrity was always a match for it and allowed him to ensure that justice was done in the end. There was often, as in Boomerang!, a subsidiary character (played by Arthur Kennedy, above, in this case) who resembled the protagonist of a classic noir, an innocent man wrongly accused, dragged down by fate or official misconduct, but we never saw the story through his eyes — we saw it through the eyes of the official (or dogged reporter) who would save him.

There are no such saviors in classic noirs — the whole burden of which is to involve us emotionally in the nightmare of the trapped man, to show us the world from his point of view, to make us feel its oppressive weight. The protagonist of a classic noir might or might not survive his nightmare, but such salvation as he occasionally does find is likely to be provisional — there is rarely any suggestion that the world which generated his nightmare is ever going to change.

This is light years away, existentially, from a film like Boomerang!, where the hero has a dark night of the soul, chooses to do the right thing, defies the corruption of his bosses, frees the innocent man and goes on to become the Attorney General of the United States. It is, in short, a film which questions and criticizes but ultimately vindicates the American legal system, affirming the efficacy and ultimate triumph of moral action within it. If Boomerang! is a film noir then I guess Mr. Smith Goes To Washington is a film noir, too, and we need some other term to describe movies like Detour, Out Of the Past and Thieves Like Us.

CHRISTMAS CIGARETTES

Nothing says “Christmas” like cigarettes — nothing evokes the spirit of the season like an armful of cigarette cartons with gay holiday designs on them . . . and when sexy Ann Sothern delivers them to your door, all you can say is, “Ho, ho, ho!”

[With thanks to the Gunslinger for the image.]

BARNUM

The 19th-Century showman P. T. Barnum is probably best known today for the circus which bears his name — the only one of the great American circuses to survive into the 21st Century — and for a line he never spoke, “There's a sucker born every minute.”

Barnum didn't see his public as suckers but as citizens of a grand republic in desperate need of cheering up. Though a religious man himself, a teetotaler and (eventually) an abolitionist, he carried a life-long resentment against the dour form of religion he grew up with in his native Connecticut. He believed that America's spiritual well-being depended on regular relief from the grim industriousness and fun-killing morality of its Puritan roots — and this he set about providing with an energy and inventiveness that still boggles the mind. In the annals of American show business, only Walt Disney comes close to being a comparable figure — and Barnum built his entertainment empire in an age when newspapers and handbills were the only mass media available to advertise his spectacles.

Barnum perpetrated hoaxes, to be sure, but never too seriously — he paid journalists to question their authenticity as a way of drumming up interest in them. He knew that people enjoy being fooled, if the foolery is entertaining enough. He had a passionate belief in the necessity of giving the public good value for its entertainment dollar, and humbug, if it's spectacular enough and outrageous enough, is always fun.

Though Barnum sponsored touring shows and circuses, the heart of his empire was the American Museum, securely anchored in downtown Manhattan. There had never been anything quite like it — part art gallery, part museum of natural history, part zoo, part carnival midway, part theater. It housed respectable paintings and sculptures, wax figures of famous people, miniature models of exotic cities and structures, human skeletons, mummies, gemstones, historical artifacts (real and bogus), fossils, stuffed and live animals and ever-changing exhibits of human “freaks”.

In addition to all this the museum hosted one of the largest theaters in New York, with its own repertory company, presenting plays (advertised as dramatized “lectures” to skirt the city's strict theatrical regulations) and variety acts, everything from ballet dancing to blackface minstrelsy.

You could say that Barnum in his museum spent his life bringing together things that the official culture of the 20th Century, spurred on by increasing specialization within the academy, did its best to separate into distinct categories and distinct venues. Art belonged in art galleries and art museums, stuffed animals belonged in natural history museums, live animals belonged in zoos, freaks and hoaxes belonged in carnival sideshows (if they belonged anywhere), dramas and variety shows belonged in specialized theaters located in theater districts.

In many ways Barnum's museum was a better and more inspiring reflection of real culture than our ghetto-ized entertainment scene — and I think you could make a case that the Internet is allowing Barnum's vision to have a rebirth in the culture of the 21st century. Boing Boing, for example, calls itself a directory of wonderful things — which is just a virtual version of Barnum's “showcase of wonders”. A blog like Tom Sutpen's If Charlie Parker Was A Gunslinger tries to open a window on visual culture with no preconceived intellectual firewalls between categories of images — and thus reflects the way we actually experience visual culture. In its own small way, this blog, partly inspired by Sutpen's enterprise, tries to do the same thing.

So Barnum is back — or perhaps he never really left, since we have always seen and experienced the world of “curiosities”, of “wonders”, of “entertainments”, of “art” the way Barnum did, as a jumble, a continuum, a conversation between different kinds of things. Now, that conversation has emerged into the light again in virtual space, as it once existed in the physical space of Barnum's museum . . . and as it exists in the physical spaces of Las Vegas, too, if you want to go there — and let's face it, almost everybody does, whether they admit it or not.