The fourth movie in the Noir Bars: New York

series from Majestic Micro Movies — extremely short tales of lost

souls in desolate bars on dead-end streets. Now playing on a computer or portable device near you — a report from girlworld:

Noir Bar #4

YouTube

Facebook Fan Page

Watch all the films in the series as they roll out, then order a stiff drink and try to forget them.

Monthly Archives: February 2010

THE SKIM

Meyer Lansky at the Hotel Nacional in Havana secretly photographed for Life Magazine in 1958, just before it all came crashing down for the mob in Cuba. Lansky was reported to be carrying several hundred K in the bag, his share of the skim from the casino at the Nacional, which he controlled.

Lansky was the guy Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista (above) brought in to clean up the casinos in Havana, which used to be cheap clip joints avoided by the high rollers. Lansky knew you had to run honest games to attract the real players. Disposing of the profits could be handled in less above-board ways. Batista and various other government officials got their share, Lansky and his underworld associates got their share — there was probably just enough left over to pay modest salaries to the nominal “owners” of the casinos.

A NEW APPROACH TO NARRATIVE

Following up on a previous essay, “An Experiment In Narrative”, Matt Barry has written a broader survey of the state of Internet cinema, in which he argues that the term “short film”, with all its (increasingly irrelevant) cultural baggage, needs to be abandoned. Distinguishing something as a “short film” implies that regular films are “long”, but today, on the Internet, regular films are short — long films are the exception. In some ways it would make more sense to refer to those things they're showing at the multiplexes as “long films”.

The question, of course, is one of orientation in a time when the mainstream of cinema is shifting. I would guess that for most people under the age of forty, most of the films they watch in any given year, by far, are short Internet movies — feature-length films, seen in theaters or on DVD, would run a distant second. So what do we mean when we talk about “the movies” today? Where is the real center of the form?

Matt also makes a useful distinction between “narrative” and “story”. To my way of thinking, a narrative, a logical exposition of a sequence of events, is not by any means always a story. To me, a story is something that makes you lean forward and say, “Wait a minute, how did this happen — what's going to happen next?” A narrative doesn't automatically do this.

Check out the essay here:

A TISSOT FOR TODAY

Completed between 1883 and 1885, this painting is known as The Sporting Ladies and also as The Circus Lover from a series called Women Of Paris.

As with several images of the circus by Tissot, and many other works as well, the painter has created a number of distinct spaces that draw us into the scene progressively — the space occupied by the gentleman leaning in towards the ladies, with the unseen part of his figure seeming to occupy our, the viewers’ space, into which the central female is peering, the space of the seated ladies, the space of the circus ring, and the space of the background seats.

The space of the circus ring is further articulated into the aerial space of the trapeze artists and the space of the clown in the sawdust and there is, as a kind of punctuation, a glimpse in the distant background of a lighted foyer opening on to the highest rung of seats.

The elegant calculation of the composition makes for a very dynamic and seductive image.

PARADISE RECLAIMED

[Photo © 1960 William Klein]

An excerpt from a 2000 profile of Jean-Luc Godard by Richard Brody in The New Yorker:

During our interview, Godard referred

to the New Wave not only as “liberating” but also as

“conservative.” On the one hand, he and his friends saw

themselves as a resistance movement against “the occupation of the

cinema by people who had no business there.” On the other, this

movement had been born in a museum, the Cinémathèque: Godard and his

peers were steeping themselves in a cinematic tradition — that of

silent films — that had disappeared almost everywhere else.

Thus, from the beginning, Godard saw the cinema as a lost paradise that

had to be reclaimed.

If love of the cinema of the past doesn't point the way to new, revolutionary

work — as love of ancient Greek art sparked the innovations of the

Renaissance — then it's just an exercise in nostalgia.

In other words, the cinema of the past can be alive as a cultural force, as it

was for the young French cinéastes of the Fifties, just as ancient Greek

art was alive for the artists of the Renaissance.

The parade has not gone by — it may even be passing this way:

NOIR BARS #3

The third movie in the Noir Bars: New York

series from Majestic Micro Movies — extremely short tales of lost

souls in desolate bars on dead-end streets. Now playing on a computer or portable device near you — a whole chain reaction of disaster:

Noir Bar #3

YouTube

Facebook Fan Page

Watch all the films in the series as they roll out, then order a stiff drink and try to forget them.

[Image by Alfred Stieglitz, 1903]

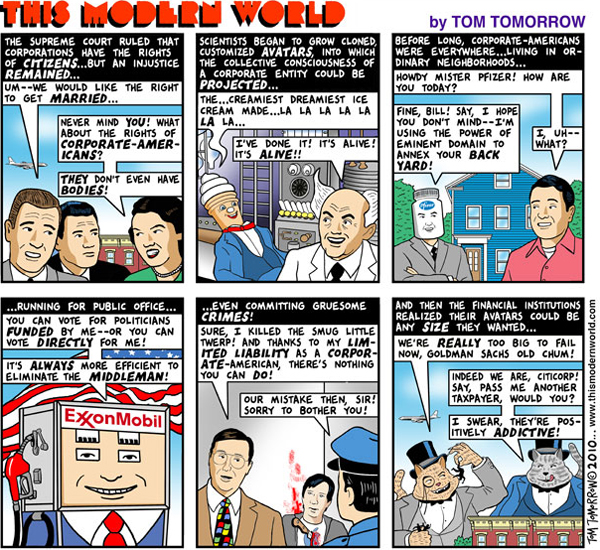

THE CORPORATE-AMERICAN

There is something fantastical, ghastly, almost demonic about seeing a corporation as somehow equivalent, existentially, to a human being. Could a religious person, for example, ever refer to Exxon Mobil as “a child of God,” as a “dear soul”? The idea is profoundly unsettling.

It doesn't seem like a view one could arrive at simply by specious legal arguments or moral depravity in the service of a political ideology — it would seem to require something more, some sort of neurological disorder, some actual and fundamental damage to the brain itself.

CRIME DOES NOT PAY

In the glory days (the 1940s and early 1950s) before the comic book industry began to censor itself, to ward off government censorship, comic books could and would show just about anything of a violent nature. Lurid, gruesome, graphic, they approached Elizabethan drama in their obsession with the bloody and the macabre.

I doubt if any of them that came into the hands of young children really rotted the kids' brains or corrupted their morals. Young children know perfectly well, from their intuitions and their dreams, that the human psyche, and thus the real world, is filled with such horror. It is only grownups who try to pretend otherwise.

A powerful art form was crippled by the state-induced censorship, though. Only today has the comic book reclaimed its right to range over the whole landscape of human experience, in the process producing some of the best fiction of our time.

[Via Golden Age Comic Book Stories, the Internet's wonder site.]

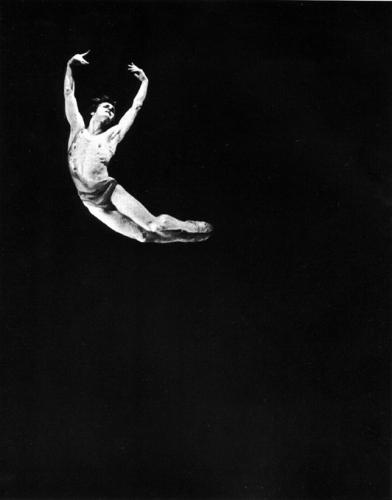

SHAUN WHITE'S STRAIGHT AIR

. . . is almost unbelievable.

He gets a lot of it, really a lot of it, and when he's at the peak of his ascent he seems to pause for a moment and then decide to come back to the earth.

Great classical ballet dancers give the same impression at the tops of their jumps. It's an uncanny illusion created by a visible relaxing of the muscles at that moment of apex, very slight, but perceptible. It seems to suggest absolute calm, absolute unconcern about the landing. It seems to suspend time along with the rules of gravity.

White does a lot more complex and astonishing things than his straight air move, a required element in the competition which he usually places at the beginning of his run — but his execution of the straight air move is an announcement of sorts, asking us to look not just at what he's doing but at how he's doing it.

It is the statement of a theme, an artist's manifesto.

The finals of the men's halfpipe in Vancouver last night made White's aesthetic ambitions clear. Going into his second run, the last run of the competition, he had already secured the gold medal. He could have slid straight down the bottom of the halfpipe to the finish line and collected his prize. But he chose to outdo his gold-medal-winning first run, and he chose to finish it with his new signature move, which he hadn't yet unveiled in the competition — the double McTwist 1260, a move so complex that it can only be followed clearly in slow motion.

[Image © 2010 New York Times]

He didn't have enough speed going up the wall to get all the air he needed for this last move, but he decided to use the air he had. He performed the move with barely enough time to get his board pointed down the side of the wall and his weight over it for his landing. He hit the snow off-balance but somehow found it again — by force of will, it seemed.

His second, wholly unnecessary run scored higher than the run that had already won him the gold. It was sublime, Homeric, transcendently beautiful.

ANOTHER NOIR BAR

Now playing on a computer or portable device near you . . . the second movie in the Noir Bars: New York

series from Majestic Micro Movies — extremely short tales of lost

souls in dark bars on dead-end streets. Have a look:

Noir Bar #2

YouTube

Facebook Fan Page

Watch all the films in the series as they roll out, then order a stiff drink and try to forget them.

[Some explicit language in this one.]

A VERMEER FOR TODAY

What is it about Vermeer? His virtuosity as a technician is thrilling, of course — but how does he invest his photo-realistic visions with such warmth, such an impression of life? The painting above revels in specificity, it enters the imagination as a place we've actually visited, but it's more than a record. As usual, Vermeer plays with frames, spaces opening onto deeper spaces, drawing us in to the scene, and commenting ironically on the act of painting itself, putting frames around life.

The profound beauty of the most ordinary things, the great gift of “the ineluctable modality of the visible”, seem to have inspired him on an almost spiritual level, and the way he communicates this to us is both complex and totally obvious — some kind of mystery hiding in plain sight.

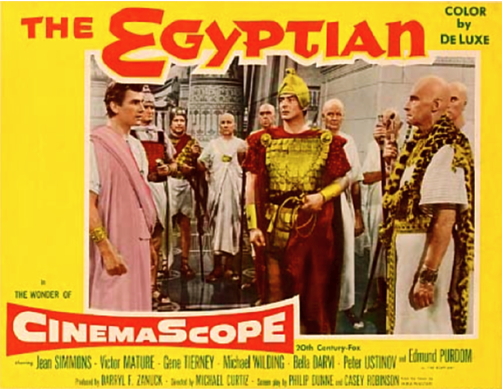

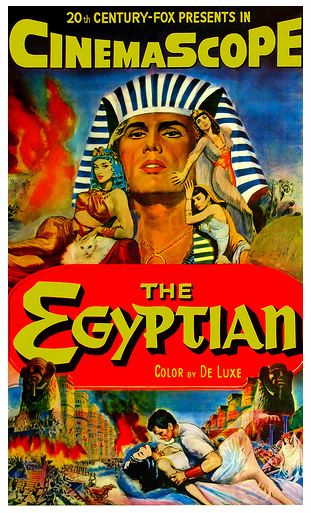

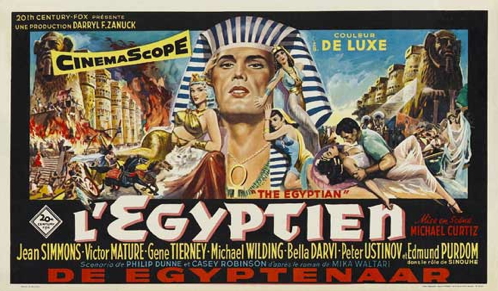

WALKING IN MEMPHIS

Some thoughts by Paul Zahl (of The Zahl File) on Jack Kerouac and his connection to Michael Curtiz's costume epic The Egyptian. Huh? Read on:

The 1954 Hollywood movie The Egyptian, a big picture, with Jean Simmons

and Michael Wilding, among many others, is hard to find — all but impossible

to find, in fact, until the days of Internet magic. (It's available on a Korean DVD.) It was produced by

Darryl F. Zanuck and directed by Michael Curtiz. Curtiz had directed

several big pictures, including Casablanca and Mildred Pierce, not to

mention The Walking Dead and Mystery of the Wax Museum.

The Egyptian tells the story of a young doctor in Ancient Egypt —

meaning Thebes, Memphis, and Luxor — who is ensnared pitifully by a

temptress known as the “Woman of Babylon”, completely loses his

self-respect, together with everything he owns as well as his post as

Physician to Pharaoh, and finally recreates himself as a

healer wandering throughout the Ancient World. He prospers, only to return home

to lose his true and loyal love, played by Jean Simmons, and to become

caught up in the failed but sublime One God movement of the Pharaoh

Akhenaten. In a touching scene that works dramatically and

cinematically, Sinuhe, the doctor, is converted to monotheism. After

all his sad experience of life, Sinuhe seeks monastic solitude in the

desert, a sadder man but much wiser.

The Egyptian is pretty good. The sets are gorgeous, the camera is

fluid and assured, the acting (with the exception of Gene Tierney, who

is miscast as Pharaoh's sister) confident if a little wooden, and the

matte paintings and miniatures convincing. Personally, I like the

religion of the film, with Akhenaten's confession of his universal faith

going down well, with pathos, at the end. Some might say that The

Egyptian is suffused with '50s-style religion in this country, but that

would be unfair. The film is so anchored in the pessimistic views —

i.e., life as an exercise in dreamy futility, with loss — of the

author of the original best-selling book, that Akhenaten's “witness” in

the last scene but one, comes off as credible, and for me even

hopeful. The novel on which The Egyptian is based, incidentally, was

written in the Finnish language by Mika Waltari. In the days of our

fathers and mothers, Waltari's novel was an international sensation.

Waltari's father, incidentally, was a Finnish Lutheran pastor. It was the Finnish Lutherans, of course, who brought us The Flying Saucer Of Love.

Here's the thing:

Jack Kerouac saw The Egyptian in a movie theater when it first came out.

He hated it!

The vehemence of Kerouac's response to this relatively standard

Hollywood production is surprising. I read his armchair review, which occurs in Some of the Dharma (page

124), three years ago and was impressed by his very negative reaction. Here is what he wrote:

WITH 'THE EGYPTIAN' Darryl Zanuck has purveyed a teaching of

viciousness and cruelty. They present him with a gold cup at banquets for this. The

author, Mika Waltari, is also guilty of the same teaching of viciousness and

cruelty. You see a scene of a man choking a woman under water. Both these men

are rich as a consequence of the world's infatuation with the forbidden murder,

— its daydreams of maniacal revenge by means of killing and Lust. Men kill

and women lust for men. Men die and women lust for men. Men, think in solitude;

learn how to live off your sowings of seed in the ground. Or work 2 weeks a

year and live in the hermitage the rest of the year, procuring your basic foods

at markets, and as your your garden grows work less, till you've learned to live

off your garden alone.

QUIETNESS AND REST THE ONLY ESCAPE.

The secret is in the desert.

Now, Ain't that Peculiar! The Egyptian tells the story of a man

disillusioned by romantic love — in the first half he loses his whole

self, his deepest self, to the wily and nefarious siren of Babylon.

The Egyptian envisions his then turning aside from the world, and

becoming a kind of medical “gentleman of the road”, a Sal Paradise of

the ancient Mediterranean. With Kerouacian pessimism, Sinuhe observes

the fruitlessness of human endeavor, and does so over and over again.

Finally, back home in Thebes — I love writing those words — he

becomes enlightened by Akhenaten, the Sun (One) worshiper, who reveals

to him that God is the whole of Reality, and that Forgiveness, of all

things, is at the core of that Reality. There is something like

pantheism here, together with absolving Christianity, and the the name

“Jesus Christ” is invoked on the end-title. How could Kerouac not have

responded positively to this, given his Christo-Buddhism, or

Buddhist-Christianity, or however you want to call his personal

synthesis?

But he didn't like the film. He focused completely on the Woman of

Babylon sequence, with its subtle, slightly-off-frame drowning of the

Siren — she survives — and the “lust of the eye” and lust of the body

which drives the story at that point. Biographers of Jack Kerouac

would probably observe in these comments his suspicion of entrapping

women and entrapped men, his frequent equation of greed and lust, and

his persistent failed efforts to choose celibacy on Buddhist grounds

— “Men . . . learn how to live off your sowings of seed in the ground [my emphasis].”

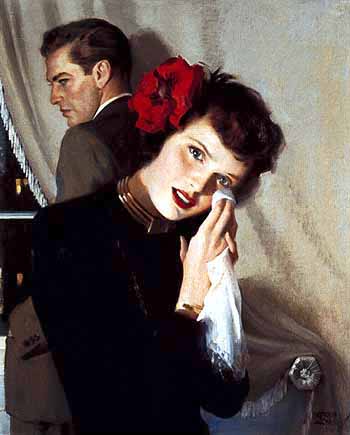

I want to guess that Kerouac got stuck on the performance by Bella

Darvi as Nefer, the Woman of Babylon, and did not consider the enduring

Treue of Jean Simmons' character, nor the emphatic world-renunciation

by Sinuhe, which begins and ends The Egyptian.

What his impassioned observations do tell us, and they read as sober

and non-Benzedrined, is that Kerouac was touchy about violence. This

is the man who would brawl in bars, mad-drunk, and then write

remorseful exhortations to the whole world to Be Kind. He was also a

man who loved women, but suspected them, and their “designs”, through

and through, with the exception of Gabrielle, his mother.

Take a look at The Egyptian. It's a good movie. Sure, it's too long.

And to be sure, there's not one word of humor. But the liturgical

scenes, with their ethereal religious chants praising “Beauty” (I

thought I could hear Lionel Ritchie's “You are so Beautiful”) — which

work! — and especially the obeisances, including Jean Simmons's, on the

steps of the temple of the One (Sun) God, are sincerely reverent, and

affecting.

You could compare the scene of Pharaoh's archers breaking into the

Temple of Aten with the Roman breach of the Temple in Nicholas Ray's

The King of Kings. The latter is bloody and sensationalistic (like the “Civil War” cards little boys loved in the '60s, by the same people who

did the “Mars Attacks” cards) — the former, sympathetic and pitiful.

My irony for today is this:

Jack Kerouac should have liked The Egyptian. The title character, take

away the toga, is the man himself.

Maybe he walked out before the end. The editor of this blog taught me never to

do that.

AN EXPERIMENT IN NARRATIVE

Matt Barry — a fellow filmmaker and blogger and collaborator on the experiment in question — just posted an insightful piece about Majestic Micro Movies on his site, The Art and Culture Of Movies. The site is filled with interesting thoughts about movies from every era . . . including a two-part essay with great screen-grabs on the films of Edwin S. Porter. (You can access Part 1 here and Part 2 here — together they'll give you a nice little overview of the landscape of early film as the era of narrative began.)

That's Matt above in the Noir Bars: New York film from Majestic Micro Movies he starred in, which will be appearing online soon. It was shot and directed by Jae Song. I know what you're thinking — it must have taken Jae forever to light that scene, with the baby spot catching Matt's eye and the ominous shadow behind him . . . but no, it was done on the fly with available light in a dark bar and a camera so small that no one knew Jae and Matt were making a movie there.

So cool.

A NOIR BAR

Today is the premiere of the first movie in the Noir Bars: New York series from Majestic Micro Movies — extremely short tales of lost souls in dark bars on dead-end streets. Have a look at it — a little Valentine from Majestic Micro Movies to you:

Noir Bar #1

YouTube

Vimeo

Facebook

Majestic Micro Movies Home Site

Watch all the films in the series as they roll out, then order a stiff drink and try to forget them.

[With thanks to American Gallery for the Andrew Loomis Ladies Home Journal cover from 1949.]

SURFING THE MICRO WAVE

First there was the French New Wave — an attempt by filmmakers to retake control of cinema from the commercial or state-sponsored studios and get back to basics.

Now there's the American Micro Wave, which is basically the same thing, necessary because the eruption of cinematic invention sparked by the young directors of the New Wave has been smothered once again in corporate standardization and dehumanization.

The Micro Wave is about micro movies. This is nothing new. Micro movies dominated the early years of cinema exhibition, and micro movies dominate the Internet. The question is, can modern micro movies on the Internet get more sophisticated than cute clips from home videos, or pseudo-narratives designed to show off the filmmakers' technical skills, basically just self-generated commercials?

In short, can modern micro movies learn to tell real stories, just as directors of the nickelodeon era learned to tell real stories?

Finally, is this new Micro Wave really a wave? Too soon to tell, unless you're in the water. You can't see a wave coming until the sea-swells meet the curve of the seabed running up to the beach, lifting a crest so high that it breaks on the sand. But you can feel it if you're out swimming in it.

All I can say is, “Come on in — the water's fine!”

[“Mermaid” illustration by D. S. Walker, with thanks as so often to Golden Age Comic Book Stories, where wonders never cease.]