Monthly Archives: May 2011

LEST WE FORGET

American Cemetery, Omaha Beach.

There are many forms of service and sacrifice for one's country, but no one can give more than they gave, which was everything they had — all their tomorrows for us and our tomorrows.

Ernie Pyle, the great poet of the dogface solidier in WWII, once told an interviewer that he never ceased to be amazed at the casualness with which an American soldier would lay down his life for his fellow soldiers. “And they didn't do it for parades or statues or glory,” Pyle said. The interviewer asked, “Then what would be a fitting memorial for a soldier like that?” “Well,” said Pyle, “the next time you pass a soldier's grave, just stop and take off your hat and say, 'Thanks, pal.' That's what they did it for.”

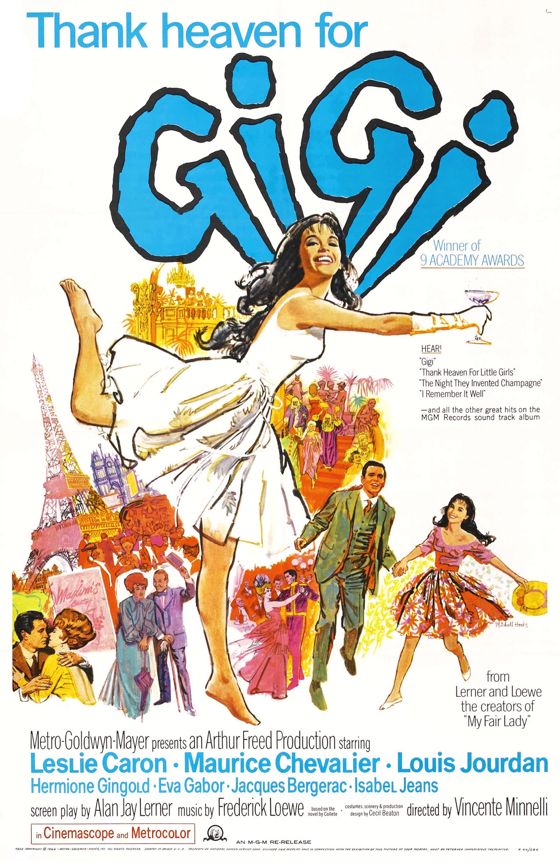

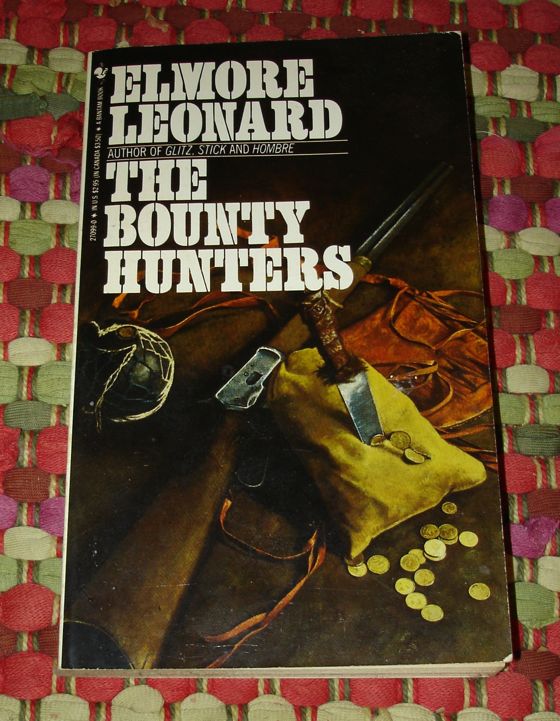

THE BOUNTY HUNTERS

Before he became the best writer of crime thrillers in modern times, and one of the best novelists of modern times, Elmore Leonard wrote Westerns. He started out writing Western short stories for the magazines that used to print such things and then in 1953 he published his first Western novel, The Bounty Hunters, which I just read.

Although it was his first novel in any genre, it possesses most of the virtues of his later works — a taut, suspenseful plot, eccentric characters, startling episodes of violence, creepy villains and a protagonist who's cool but not too virtuous. It's invested with a strong sense of place, in this instance the Arizona Territory and Mexico, and the prose is spare but lively. The story moves.

The tale reworks a lot of familiar Western conventions, as most Westerns do — that's part of the challenge of genre fiction. One can see elements borrowed from Western movies and given a harder, sharper edge.

It's a fine piece of writing and a superbly entertaining read.

I'm going to go back now and read all the short stories Leonard wrote before The Bounty Hunters, and then proceed on to everything he wrote in the Western genre. Having read most of his contemporary thrillers, I feel as though I've discovered a brand new author. There are reports that he's thinking of writing a new Western. I hope it's true, because it would be fascinating to see how he'd approach his first love after achieving mastery and fame with other kinds of material.

Come on, Elmore — let's go to Missouri.

SPICY

If you're into erotica, of a decidedly explicit type, you might enjoy

this

short story I just discovered, by Rachel Carlyle, about a

naughty girl detective, set in 1936. Quite

graphic — this is fair warning — but done with tongue firmly in cheek (among other places):

The Adventures Of Spicy La Tour, Girl Detective: The Case Of the Missing Muffin

Available for the Kindle — or for Kindle readers, which can be

downloaded

for free and used on most computers and portable devices. It costs 99 cents.

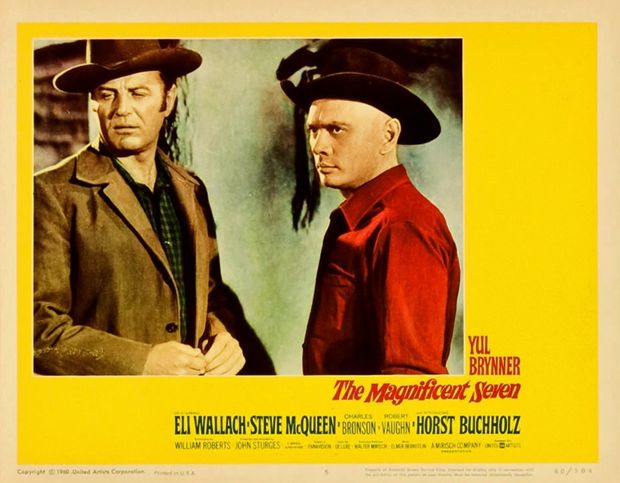

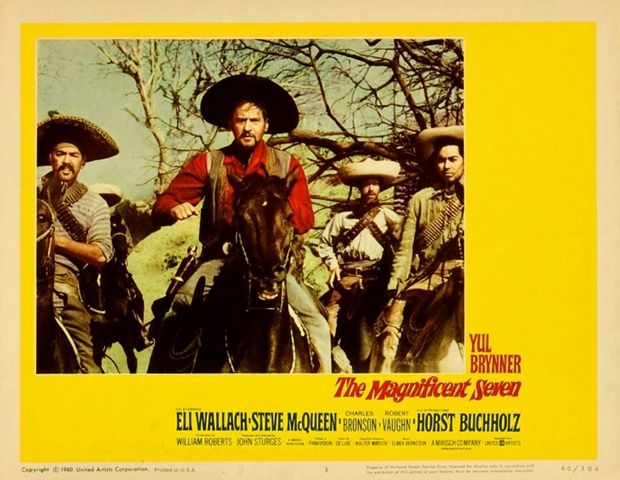

THE HATS OF THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN

The Magnificent Seven is one of the most entertaining and influential Westerns ever made but it has some problems that keep it from being a great Western and they start with the hats worn by the seven gunslingers, too many of which are small and jaunty. They're TV cowboy hats, Rat Pack cowboy hats. Yul Brynner's is the worst. It's sort of a tiny tricorne, like the one the poet Marianne Moore sometimes wore. On her it looked cute. On Brynner it looks cute. A cowboy's hat should not look cute.

An actor playing a cowboy may not need a hat with a brim wide enough to keep the sun out of his eyes, or with a tall crown to keep his scalp cool, because he doesn't spend all day on horseback under a blazing sun — he has a trailer he can retire to between rides. But the character he's playing should look as though he could spend all day under a blazing sun and have a hat suitable to the activity.

Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson and James Coburn wear hats that are adequately large, barely, but they've rolled the brims up on the sides to convey a kind of hip jauntiness. Hip jauntiness is not a primary cowboy virtue. Still, it's worth pointing out that the three actors who wear more or less acceptable hats all went on to have careers as the stars of memorable action films, including many Westerns, while those who wear hats that aspire to the condition of the modern fedora did not.

When Eli Wallach and his band of Mexican thieves gallop onto the scene, with their grand and authentic-looking sombreros, your first impulse is to root for them in the battle over the beleaguered peasant village, because they wear the hats of men.

In a Western, wearing clothing that at least approximates the style of the period the film is set in has one great advantage — the film has less of a tendency to date. It always looks classic.

Brynner doesn't give a bad performance in The Magnificent Seven, but he doesn't quite inhabit the Western genre. He has a peculiar regal walk which commentators on the film have often drawn attention to — the walk of an actor who has played the king of Siam a few too many times. It doesn't have the natural, fluid grace of a real cowboy's walk, a real horseman's walk. He also has a Russian accent, which the film tries to sell as a Cajun accent — a preposterous ploy that only draws more attention to its anomalous quality.

His silly little hat becomes a symbol of his unconvincing Western persona — inescapable even when he's not talking or walking. A respectable Western hat would have gone a long way towards reconciling us to that exotic persona.

The same is true of the German actor Horst Buchholz, whose German accent the film tries to sell as Mexican. He has the physical grace of a cowboy, and when he dons a big sombrero for a few scenes he actually looks like a cowboy. At all other times his dainty little hat brands him as an impostor.

What were they thinking?

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

My niece Nora, 14, wrote a report for school on Orson Welles's infamous “War Of the Worlds” radio broadcast. It's really superb — check it out here:

The War Of the Worlds: Essay by Nora Rossi

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS: ESSAY BY NORA ROSSI

“Something’s wriggling out of the shadow . . . It’s as large as a bear and glistens like wet leather. But that face, it . . . it’s indescribable . . . The eyes are black and gleam like a serpent. The mouth is V-shaped with saliva dripping from its rimless lips that seem to quiver and pulsate . . .” It’s a war of the worlds! It was 1938, a Sunday, on the eve of Halloween just as the sun made its way below the horizon, and the moon began to warily take its place. Little did the people of the seemingly secure Grover’s Mill know that this could very well be the last night sky they would ever see. The last sky the entire planet might see . . . Millions of Americans sat glued to their radios as a familiar evening broadcast of dance music was suddenly interrupted by an urgent new bulletin. Invaders from Mars were attacking! This spine-chilling broadcast bent believers to its will in such a way that it is still considered the single most important event in radio history today.

The “War of the Worlds” radio-play was the brainchild of Orson Welles, a talented, 23-year-old actor, producer, and theater director. In order to fill empty air space, CBS offered Welles and his dramatic group, the Mercury Players, a program every Sunday night called Mercury Theater on the Air. The program was broadcast out of New York City, and included dramatic adaptations of plays and books. On the night in question, Orson Welles was presenting an adaptation of the famous book The War of the Worlds by H. G. Welles (written 1898). Orson, his partner John Houseman, the writer Howard Koch, and the small cast of Mercury Players, decided to present the War of the Worlds as if it were the actual event happening in real time. The audience was lulled by the “soothing” sounds of the dance band music, when suddenly one of the actors in a carefully planned interruption pretended to be an actual CBS network announcer with frightening breaking news, from New Jersey. America was under attack from Martians in giant war machines. For the next hour, the story escalated, with more detailed information as the event unfolded. According to the “newsmen,” cities were being destroyed, state militias were demolished, dark, poisonous alien gas was purposefully unleashed across the country, citizens were getting eaten by the invaders, and others were being crushed by huge, metal Martian machines. Clearly the end of the world was at hand. The precision, detail, and very powerful acting made the broadcast realistic, and created doubt even in the minds of people who thought they could just shrug it off as “nonsense.”

It is estimated that there were about nine million Americans across the country listening to the broadcast that night. Many were entertained and amused. Many did not know what to think or how to react. There’s no way to know how many people were actually frightened. But we do know that about 1,750,000 people were scared enough to take some action. (Bogdanovich, Welles, 346) Despite the fact that there were multiple reminders that it was just a fictional presentation, imaginations ran wild.

Panic was rampant. Emergency switchboards were on overload. People blocked off their doors and hid in their attics and basements. Shops closed, theaters closed, churches were filled, guns were cocked, and people were screaming in the streets, “The world is ending! The world is ending!” Many fled. Others organized small, armed resistances. Some people thought bigger. Governor Earle of Pennsylvania volunteered his state’s militia to help New Jersey fend off the Martians. A group of twenty families ran out of their apartment building with wet towels on their faces to “repel Martian rays.” Hospitals were flooded with offers from nurses and doctors to help out with all the “war casualties.” A modern day Paul Revere, blowing a loud horn and screaming warnings of the Martian invaders, motored through the streets of Baltimore. One man “bound for open country” had driven away for about ten miles, until he realized that his poor dog was still tied up in his backyard, so he sped all the way back to rescue him, “risking” his life against the aliens. It was recorded that one man almost drank a bottle of poison, telling his wife, “I’d rather die this way than that!” (Although were no actual deaths or suicides on record.) Rhode Island’s electric company was prompted into considering turning off all the lights in the entire city “to make it a less visible target.” (Oxford, 184 and 185)

Why did so many people believe that the broadcast was real? One of the reasons was the artistry of the broadcast itself. Orson cleverly planned every detail. He used real names of actual places and simulated both the “live” band music and the “broadcasters” with perfect skill. He knew what competing radio shows were on that night and when people would be likely to switch over to CBS. The actors did a superb job, including imitating the voice of President Roosevelt. Orson also knew how to build the intensity of the story for maximum dramatic effect. Another reason that the broadcast was so believable was that many listeners came in part way during the story and did not hear any of the four announcements reminding people that it was just a radio-play. Even more people heard about the alien invasion second-hand. Rumors spread like wild fire. Rumors and wild imaginations led to many false, eyewitness reports. Panic caused people to see and hear things that were not actually occurring, which only increased the panic in a vicious cycle. For example, one man in Grover’s Mill shot up a deathly, alien war machine with his shot gun, only to discover later that is was just his neighbor’s rather humdrum water tower. Some New Yorkers believed they heard Martian flying machines, or weapons firing, or saw the city on fire. Another man flipped his car over twice as he drove 80 miles an hour trying to escape Martian death rays. (Oxford, 184, 185) False eyewitness reports were widespread and fed the story even more convincingly than the broadcast itself. Another contributing factor was the newness of radio. In 1938, people were naïve about joke broadcasts. These were days before, Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Updates,” or Monty Python’s Flying Circus, or Steve Colbert. If the news (especially CBS) said something was true, people tended to believe it.

It’s one thing to try to understand why people believed it, but it’s another thing entirely to try to comprehend why people were so afraid. To grasp this, it is necessary to look at the historical context of the event. The stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression that followed it had a profound emotional and psychological effect on the American people. (Rosenburg, 1) Their sense of security in their society had been badly shaken. In 1938, most Americans were still struggling to get back on their feet. Optimism for the future was at all time low. Equally important were the events unfolding in Europe and Asia. Spain was in the middle of a civil war between socialists, fascists, and royalists. Japan began a series of invasions into China, killing thousands of innocent people. (Miller, 1and 2) Hitler was on the rise, making inflammatory speeches and building up a massive military. His attacks on Jews were escalating. In 1938, he invaded and took over Austria, and began his invasion of Czechoslovakia. (World History, 1938-1939, 3) Many Americans watched newsreels or listened to radio broadcast of Hitler’s speeches. In response, America was building up its army and its navy. Many Americans began to think that we would be drawn into another World War, so soon after the first one. This created an atmosphere of tension, and underlying fear. (Rosenburg, 1, 2) In fact, when Orson’s broadcast reported that “shells were falling” towards Earth, many believed that it was the beginning of Hitler’s assault of America. (Lovgen, 1) Houseman himself recognized later the importance of the historical context, when he said, “Only after the fact, did we perceive how ready and resonant the world was for the tale.” (Oxford 189)

Newspapers saw themselves as the voice of calm reason in troubled times. This made them particularly hostile about the broadcast. As it turns out, many of the newspaper reports were inaccurate and exaggerated. Newspapers reported suicides, heart attacks, and widespread destruction of property, and held the Mercury Theater responsible. Some accused the newspapers of being spiteful and jealous because newspapers had been losing more and more popularity and advertising money to radios. Newspapers used Orson’s broadcast as a way of pointing out the dangers of impulsive broadcasts. As a form of mass media, radios were capable of trickery and deception.

Before the “War of the Worlds” broadcast had even ended, cops were already storming CBS Studios. Fortunately, they didn’t know who to arrest — or even what the crime was — but they were ready. By the next morning, the stories were all over the newspapers. When people learned that it had all been a hoax, most responded with good humor. Many did not. The mayor of Flint, Michigan threatened to personally find Orson Welles and punch him in the nose. Some legislators, led by Iowa’s Senator Herring, called for new laws to prevent anything like this from happening again. The federal communications commission, the government agency which supervised radio, called Orson Welles a “terrorist” and tried unsuccessfully to decide on a new balance between censorship and free speech. Many denied ever having been duped in the first place. The newspaper, however, kept their pressure on Orson Welles, and soon he was facing $12 million in lawsuits (Bogdanovich, Welles, 19). In time, people came to the conclusion that the broadcast technically wasn’t even a legal offense, so the lawsuits were dropped.

Instead of punishment, the Mercury Theater’s popularity shot up. Campbell’s Soup became their first sponsor. And as for Welles, he instantly became an international celebrity. Throughout the start of the innumerable interviews Welles faced, he claimed over and over that all along that he and his crew had “no idea” that people would take the broadcast so seriously.

Hollywood offered him contracts and he went on to direct major motion pictures, including Citizen Kane, and The Magnificent Ambersons. In later years, Welles revealed that he did, in fact, know exactly the response his “War of the Worlds” broadcast would create, just not quite the magnitude (Bogdanovich, Welles, 18). He admitted that he apparently had said to Mercury Theater players, “Let’s do something impossible, make them believe it, then show them it’s only radio.” (Taylor, 38)

In 1938, it was easy for Americans to see how Hitler manipulated the media to create

fear, panic, and blinding hatred. But no one believed that it would ever happen here. Orson Welles showed the country how susceptible we all are to the powers of the media. It has been over seventy years since the “War of the Worlds” broadcast, but the issues it raised are just as relevant today. With the birth of television and Internet, news can spread quicker than ever before. Not all the news that gets spread is accurate, of course, but it can still influence the way people think and how they act. Networks, broadcasters, and websites need to be thoughtful and responsible. Different networks are run by different political sides, which makes their credibility suspect. (For example: Fox News VS. MSNBC) Therefore, it is crucial that every individual be smart about how he or she interprets, believes, and handles mass media “news.” As Orson Welles decorously described, “War of the Worlds’” was, “The Mercury Theater’s own radio version of dressing up in a sheet and jumping out of a bush and saying ‘boo!’” We must always to remember to look for the sheet.

Bibliography

Edward, Oxford. “Night of the Martians.” American Experiences: Reading in American History. Volume 2. New York: Pearson Education Inc., 2005. 179-190. Print.

Gale. “Welles Broadcasts the War of the Worlds, October 30, 1938.” DISCovering World History. Online Detroit, 2003. Web. 22 Jan. 2011.

<http://find.galegroup.com>.

Lovgen, Stephan. “”War of the Worlds”: Behind the 1938 Radio Show Panic.” National Geographic. N.p., 17 June 2005. Web. 24 Jan. 2011. <http://new.nationalgeographic.com>.

Miller, David. “World History Timelines, 1938.” Din-Timelines.com. N.p., 2002. Web. 24 Jan. 2011. <http://dintimelines.com/1938_timeline.shtml >.

Rosenburg, Jennifer. “”The Great Depression.” About.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Jan. 2011. <http://history1900s.about.com>.

Taylor, John. Orson Welles. Boston: Little, Brown And Company, 1986. Print.

Welles, Orson., Peter Bogdonavich., and Rosenbaum, Ed. This Is Orson Welles. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1992. Print.

“World History, 1938-1939.” MultiEducator, Inc., 2000. Web. 20 Jan. 2011.

<http://www.historycentral.com>.

AN ISAK DINESEN QUOTE FOR TODAY

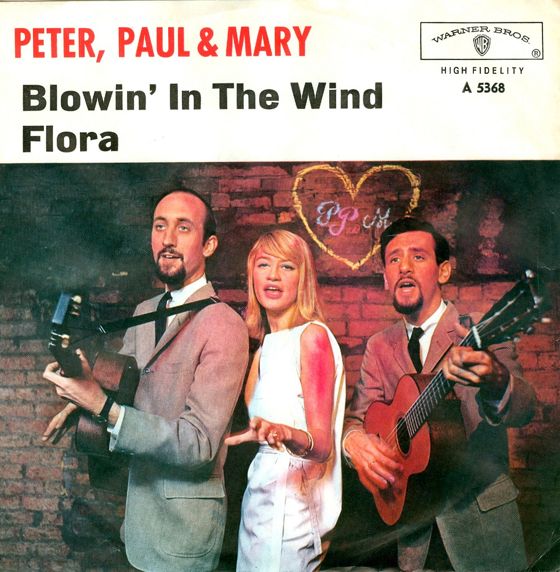

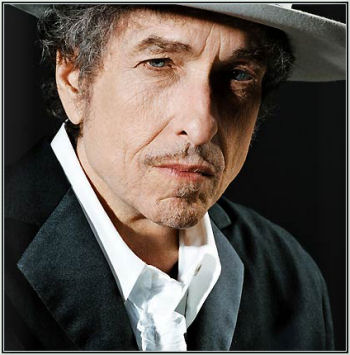

BOB DYLAN

Bob Dylan turns seventy today.

I first heard a Bob Dylan song in the summer of 1963, when I was 13.

It was Peter, Paul and Mary's cover of “Blowin' In the Wind”. Just

about everybody heard that version of the song in the summer of 1963 —

it made it to number 2 on the Billboard charts and got lots of radio

play.

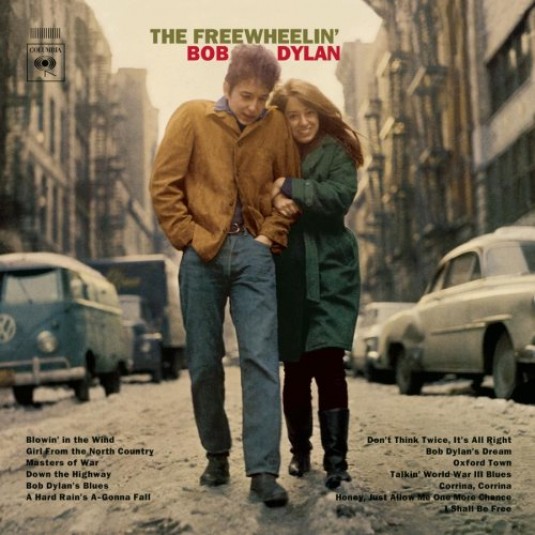

In the Fall of that year I went off to boarding school and a classmate

had brought with him an LP of The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. That was the

first Dylan album I ever heard.

So from the onset of puberty until today, Bob Dylan has been with me. He helped me grow up when I was a teenager, he helped me get

old. He helped me with belief and with unbelief.

Most of all he helped me with the problem of losing things. All of

life is about losing things — loves, innocence, friends, dreams. In

the end, we lose everything, in that pine box for all eternity. And

this is cool — it's what we're here to do. Lose. “The stars are

threshed, as souls are threshed from their husks,” is how William Blake

put it. Dylan said, “Just when you think you've lost everything, you

find out you can always lose a little more.”

The world, especially the modern world, tells us we can have

everything. In truth, we can have nothing, except what's left when

we've lost everything. Dylan sings about what that is, too.

Prophet, wise counselor, mentor, heckler, song and dance man — Bob Dylan has walked beside me every

step of the way through my adult life. Even when I lost sight of

him, he kept up with me, and was there when I needed him. Even when I gave up on him, he never gave up on me. “You might need this song someday,” he's always said, “so here it is.”

I know he would not want any thanks for this — the gifts he had to

give weren't his. He found them somewhere, and passed them along. He

never got adjusted to this world, and has reminded me that I shouldn't

get adjusted to it either. We've got business elsewhere.

SOMETIMES IT'S NICE

. . . to think about Françoise Dorléac.

[Image courtesy of Facebook friend Farran Smith Nehme.]

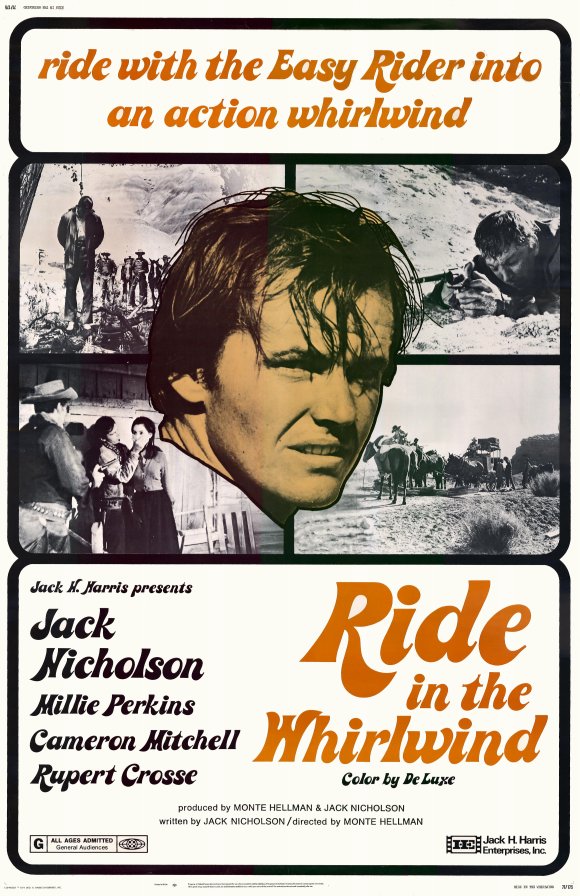

A WESTERN MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

This is a poster from a 1971 re-release of the film, orginally made in 1965. The tag line of course references Easy Rider, released in 1969, which had made Nicholson a marketable personality. The film was financed by Roger Corman and made back-to-back with another Hellman Western, The Shooting, near Kanab, Utah. The films were then sold to a distributor who sold them directly to television. Ride In the Whirlwind was subsequently released theatrically on a couple of occasions and became a huge hit in France, especially among cinéastes there, who have lionized Hellman ever since.

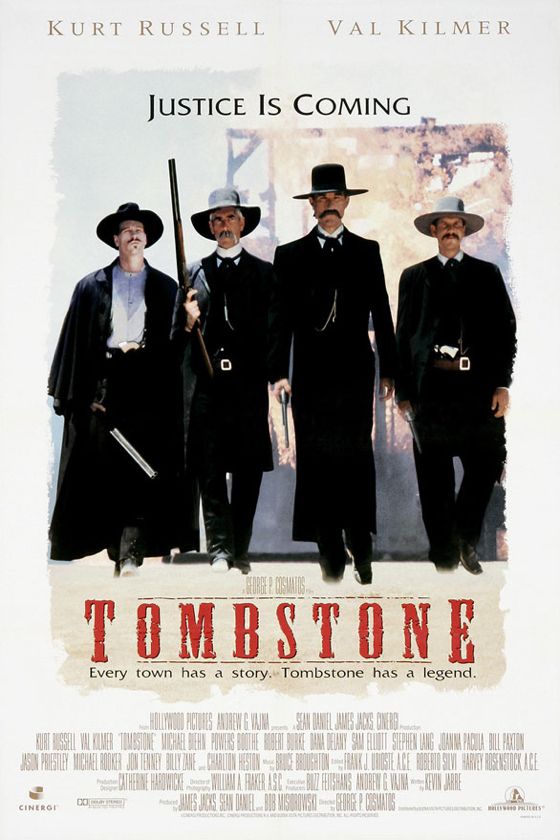

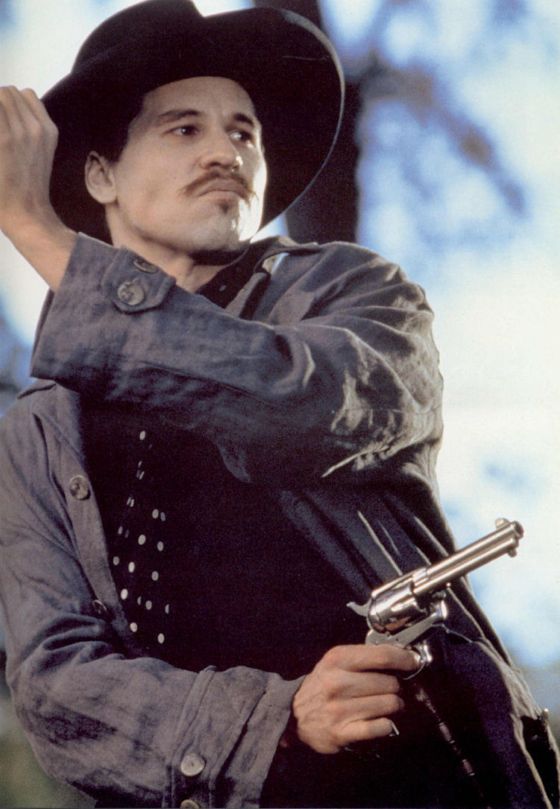

TOMBSTONE

In the wake of my friend Kevin Jarre's recent death, I decided, fearfully, to re-watch the movie that might have been his masterpiece, Tombstone, released in 1993 as “A George P. Cosmatos Film”.

I watched it for the first time, when it came out, in a state of sorrow, but this time I watched it in a state of rage. Then, one could see it as a lost opportunity for cinema, for the Western, and for Kevin. Now that he's gone one has to view it as the last opportunity for Kevin, who had the ability once to resuscitate not just the Hollywood Western, but Hollywood itself.

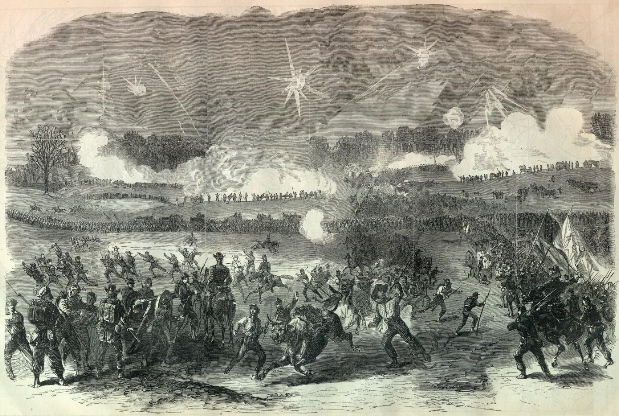

When I read his original 138-page draft of the script, not long before Kevin went off to start directing the film, I believed I had encountered something momentous. “This movie,” I said to him, “is going to be like Jackson's flank march at the Battle of Chancellorsville.” That march was a recklessly bold move by most of Lee's available forces to strike the rear of the overwhelmingly superior Union forces confronting him. While Jackson was on the move, Lee would be totally vulnerable to even a modest Union advance. If the march had been detected while in progress, Lee's whole army could have been crushed in detail.

It was not detected, it took the Union forces totally by surprise and sent them into a full-on rout. It turned what was a stalemate at best into an impossible victory.

I associated this with the movie Kevin was about to make because I knew that Kevin had conceived of a film which would be both stunning, artistically, and wildly commercial. Hollywood would not know what had hit it. Kevin had revived the craft of storytelling from Hollywood's Golden Age, brought it forward into the modern era and opened a way back into films that were both entertaining and powerful, exhilarating and profound.

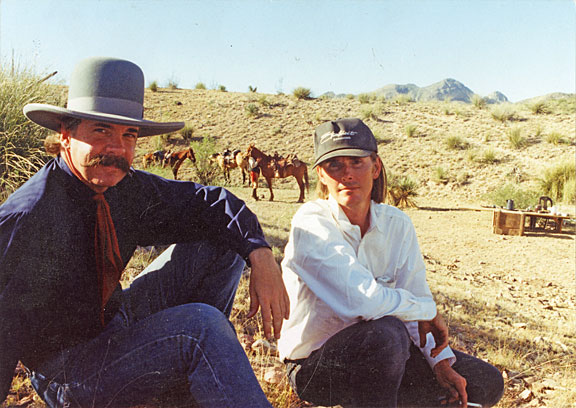

Kevin (above right, on the set) lasted only a few weeks as director of the film. I can't say of my own knowledge why he was replaced. There are stories of eccentric behavior on his part, and of falling behind schedule. I do know that the power on the production shifted to mediocrities, and that they trashed his vision. Enough of it remained to make the film beloved by fans of the Western and a solid hit at the box office, but enough of it remained also to make clear what it could have been.

Kevin cast the film, of course, and supervised the design of the production. Every choice he made on those fronts was pitch-perfect. Some of the footage he shot remains in the film, and all of it is breathtaking, worthy of John Ford, a comparison I don't make lightly. The rest of the film looks like crap, like a high-class TV movie. About 30 pages of Kevin's script were discarded, and Kurt Russell and Val Kilmer worked with the director who replaced Kevin, George Cosmatos, and with a journeyman screenwriter named John Fasano to “improve” existing pages.

Everything done after Kevin was fired cheapened and diminished the film. After the film was favorably received by critics and audiences, the mediocrities were proud to take credit for the cheapening and diminishing, as though these things had actually been what “saved” the picture and made it work.

These people didn't just want to take the miraculous gift Kevin had given them — they wanted to pretend that they had given it to themselves.

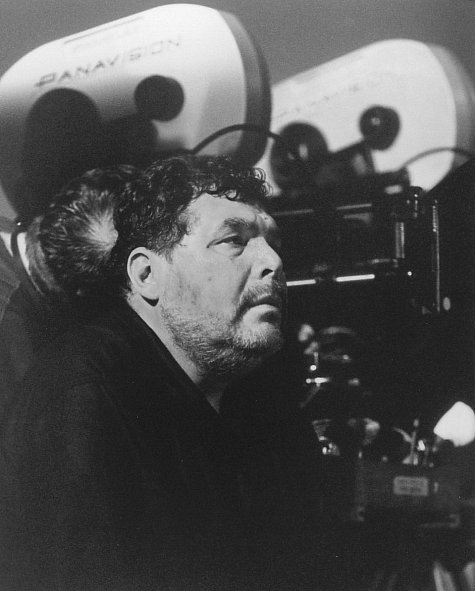

In his director's commentary on the DVD, George Cosmatos (above) takes full credit for the historically authentic details of the story and look of the film, even though he had nothing to do with these things. He also reveals the secrets of his approach to shooting the film, which involved using multiple cameras to record each scene, so the editor could make the choices he didn't know how to make on the set, and varying the style of the shots as much as possible, to create “interest”. This is the craft of a journeyman, at best. Cosmatos was a competent journeyman.

After Cosmatos died, Kurt Russell “revealed” that in fact he himself had directed the film after Kevin left, using Cosmatos as a front. He did it by stealth, giving the stooge Cosmatos shot-lists the night before each day's work and executing his ideas on the set by a series of hand signals he and Cosmatos had worked out. This would constitute the first time in film history that a movie has been secretly directed by someone without anyone else on the production suspecting the fact. The idea that you can direct a film with shot-lists and hand signals is beyond ludicrous — it's pathetic.

Russell and Cosmatos seem to have known so little about what directing a film actually entails, or I should say what directing a film well actually entails, that they may have believed their sad fantasies of themselves at the true auteurs of Tombstone. In any case, Cosmatos probably knew he could get away with retailing his fantasies on the DVD because Kevin was never much interested in re-fighting the battle of Tombstone in public. Russell certainly knew that he could get away with trashing Cosmatos's contribution to the film, such as it was, because Cosmatos could not argue back from the grave.

I knew Cosmatos slightly, and I know he was extremely proud of having directed Tombstone. It's not easy to replace a director while a shoot is in progress, and Cosmatos got the job done, however one might evaluate the quality of his work. I have a lot of respect for Russell as an actor, and he gave a fine performance in Tombstone — but even if he did secretly direct the very badly directed film, the fact remains that decimating Cosmatos's legacy the way he did, when Cosmatos was no longer around to defend it, strikes me as just this side of nauseating. Russell should have put his name on the film as its director or kept his mouth shut. If the film had tanked at the box office and had no reputation today, I strongly suspect that he would have kept the secret of his extraordinary accomplishment to himself.

People are used to merely throwing up their hands at dishonorable behavior like this because “it's just the way Hollywood works”. But it only works that way because enough people throw up their hands, and in many cases actually respect the yacks for possessing enough power to behave like insolent curs and get away with it.

In the interview in which Russell revealed his secret authorship of Tombstone, he said he respected Kevin Costner for trying to prevent the release of Tombstone, so it couldn't compete with Costner's (far inferior) version of the tale, Wyatt Earp. “He was playing hardball,” Russell said. No, he wasn't playing hardball. In hardball, as Earl Weaver once said, “you've got to put the ball over the plate and give the other fellow his chance”. Men play hardball. Collapsed males play the Hollywood game.

I think the rage I felt watching Tombstone again is useful — following the principle that “the tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction”. The moment has come when filmmakers, and the culture, need to say, as Wyatt Earp says in Kevin's script, when he's had enough of the insolence of the curs, “You tell 'em I'm coming . . . and hell's coming with me, you hear? Hell's coming with me!”

Anyone who has a problem with this can step right up and get their time. I'm your huckleberry.

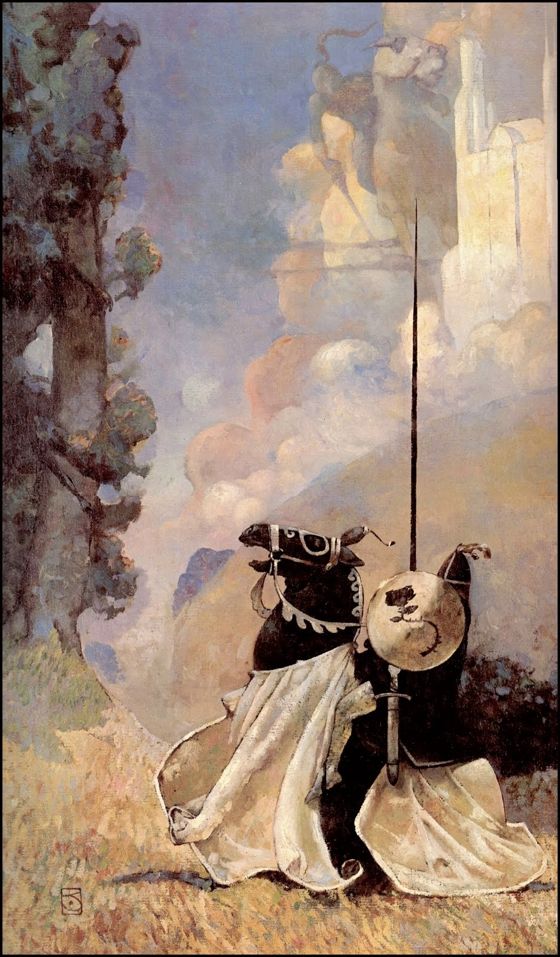

JEFFREY JONES

Jeffrey Catherine Jones died yesterday at the age of 67. Born male, Jones had a sex change operation later in life. Her style of illustration often echoed Frank Frazetta's, though she had great range and Frazetta once called her “the greatest living painter”. The influence must have gone both ways.

Jones admired the illustrators of the generation before hers and Frazetta's, especially those of the Brandywine school, and the image above, Black Rose, from 1972, is a kind of homage to the greatest of the Brandywine artists, N. C. Wyeth.

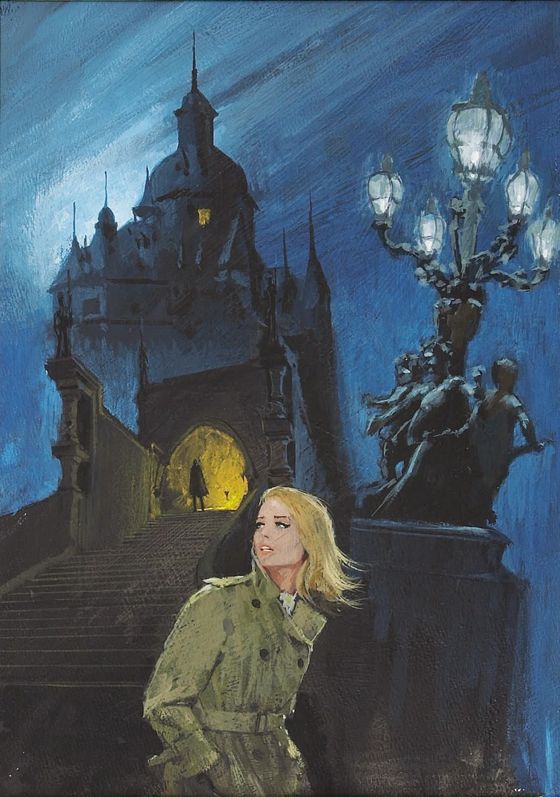

A MORT ENGLE FOR TODAY

Paperback cover, The Evil Of Time, 1967.

AN AUGUST BLESER FOR TODAY

Mishap In the Dining Room