Category Archives: Main Page

THE OGRE'S FEATHERS

Help Michael Almereyda finish his new short film, a timeless tale about goodness in the face of selfishness and suffering:

The Ogre's Feathers

As little as one dollar helps — thirty-five dollars gets you a DVD of the film, a signed note of thanks and a warm sense of service to cinema.

AN ED BALCOURT FOR TODAY

Illustration, For Men Only magazine.

A CHARLES ZINGARO FOR TODAY

“The Knockdown”, Men's Adventure magazine illustration.

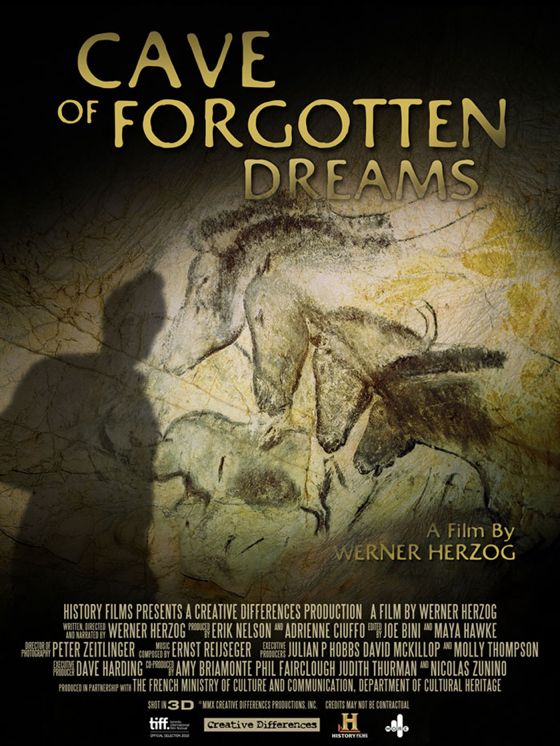

CHAUVET

Yesterday afternoon I sat in a dark movie theater in the middle of the Mojave Desert and, thanks to some 21st-Century technology, stared into a dark cave in the south of France whose walls contain what are thought to be the earliest paintings by human beings ever discovered, some 30,000 years old.

I was, of course, watching Werner Herzog's 3D documentary Cave Of Forgotten Dreams. Because of the precious nature and fragility of the cave paintings, the public has never been and never will be allowed to visit the cave, which is accessible only to scientists and historians, but Herzog was allowed to film it to show off its wonders to the world.

The 3D process he used is illuminating, not only because it conveys a visceral sense of the spooky cave environment but also because the artists who made the paintings used the irregular surfaces of the cave walls as elements of their work, often suggesting the physical mass of the animals they depicted, giving the images at times the quality of relief sculptures.

One has to strain to imagine the age of the paintings because they do not look old. They are well preserved, because the cave was sealed off by a rock slide about 10,000 years ago, but the art itself is fresh and alive, and breathtakingly beautiful. The images pulse with desire — they mostly depict animals that were hunted by Paleolithic men for survival — but also with awe and respect. The animals are rendered with powerful suggestions of movement and grace, their beauty as living creatures fully appreciated.

Here, for example, are the earliest painted representations of horses, and they can stand as works of art alongside the horses of the Parthenon Frieze, the Byzantine Horses of San Marco, the horses in a John Ford film. They summon up the vital spirit of horses in the flesh and in movement.

Human beings have created no greater works of art in the 30,000 years that have passed since “primitive men” crafted these images. This is humbling in one sense, but also invigorating. The images remind us of what is distinct about our species, this ability to make not just useful things, of increasing complexity, but sublimely beautiful things, of inexhaustible complexity. It's a complexity that transcends the material plane, and can only be called spiritual, and it's found, fully developed, in Chauvet Cave.

Our ancestors were fully human when they made these works of art — when one of them stenciled the outline of his hand on the cave wall — and we can look at them to remind ourselves what being fully human means.

A MOVIE MUSICAL POSTER FOR TODAY

LEST WE FORGET

American Cemetery, Omaha Beach.

There are many forms of service and sacrifice for one's country, but no one can give more than they gave, which was everything they had — all their tomorrows for us and our tomorrows.

Ernie Pyle, the great poet of the dogface solidier in WWII, once told an interviewer that he never ceased to be amazed at the casualness with which an American soldier would lay down his life for his fellow soldiers. “And they didn't do it for parades or statues or glory,” Pyle said. The interviewer asked, “Then what would be a fitting memorial for a soldier like that?” “Well,” said Pyle, “the next time you pass a soldier's grave, just stop and take off your hat and say, 'Thanks, pal.' That's what they did it for.”

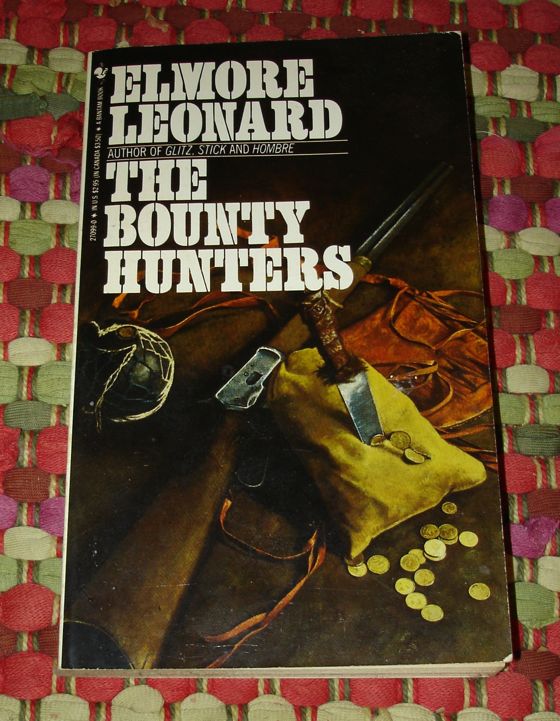

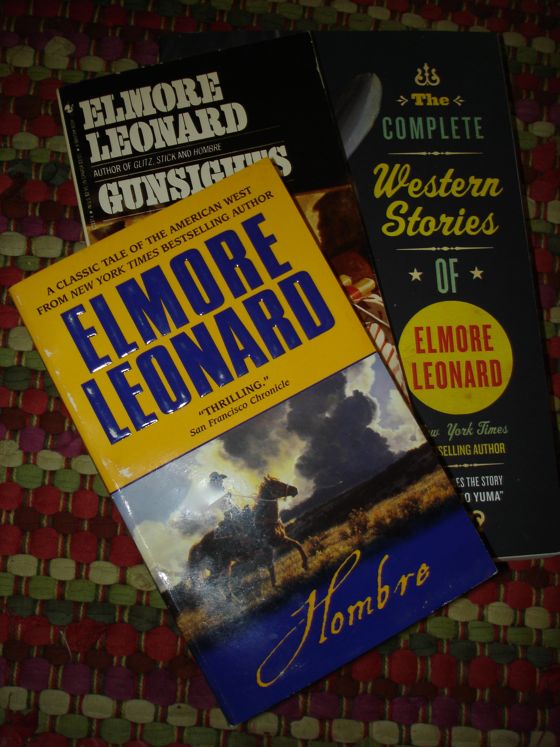

THE BOUNTY HUNTERS

Before he became the best writer of crime thrillers in modern times, and one of the best novelists of modern times, Elmore Leonard wrote Westerns. He started out writing Western short stories for the magazines that used to print such things and then in 1953 he published his first Western novel, The Bounty Hunters, which I just read.

Although it was his first novel in any genre, it possesses most of the virtues of his later works — a taut, suspenseful plot, eccentric characters, startling episodes of violence, creepy villains and a protagonist who's cool but not too virtuous. It's invested with a strong sense of place, in this instance the Arizona Territory and Mexico, and the prose is spare but lively. The story moves.

The tale reworks a lot of familiar Western conventions, as most Westerns do — that's part of the challenge of genre fiction. One can see elements borrowed from Western movies and given a harder, sharper edge.

It's a fine piece of writing and a superbly entertaining read.

I'm going to go back now and read all the short stories Leonard wrote before The Bounty Hunters, and then proceed on to everything he wrote in the Western genre. Having read most of his contemporary thrillers, I feel as though I've discovered a brand new author. There are reports that he's thinking of writing a new Western. I hope it's true, because it would be fascinating to see how he'd approach his first love after achieving mastery and fame with other kinds of material.

Come on, Elmore — let's go to Missouri.

SPICY

If you're into erotica, of a decidedly explicit type, you might enjoy

this

short story I just discovered, by Rachel Carlyle, about a

naughty girl detective, set in 1936. Quite

graphic — this is fair warning — but done with tongue firmly in cheek (among other places):

The Adventures Of Spicy La Tour, Girl Detective: The Case Of the Missing Muffin

Available for the Kindle — or for Kindle readers, which can be

downloaded

for free and used on most computers and portable devices. It costs 99 cents.

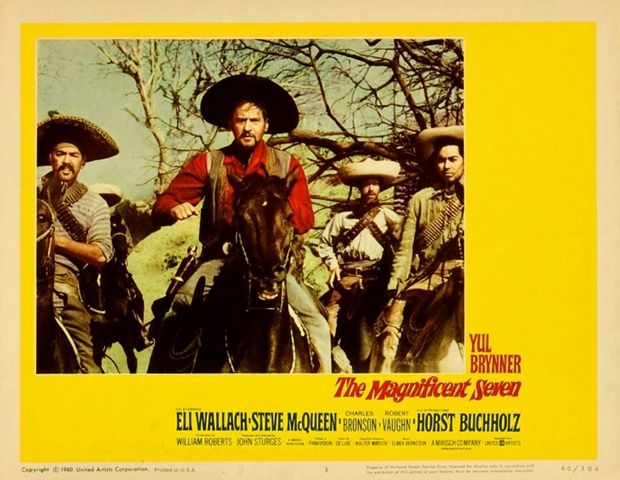

THE HATS OF THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN

The Magnificent Seven is one of the most entertaining and influential Westerns ever made but it has some problems that keep it from being a great Western and they start with the hats worn by the seven gunslingers, too many of which are small and jaunty. They're TV cowboy hats, Rat Pack cowboy hats. Yul Brynner's is the worst. It's sort of a tiny tricorne, like the one the poet Marianne Moore sometimes wore. On her it looked cute. On Brynner it looks cute. A cowboy's hat should not look cute.

An actor playing a cowboy may not need a hat with a brim wide enough to keep the sun out of his eyes, or with a tall crown to keep his scalp cool, because he doesn't spend all day on horseback under a blazing sun — he has a trailer he can retire to between rides. But the character he's playing should look as though he could spend all day under a blazing sun and have a hat suitable to the activity.

Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson and James Coburn wear hats that are adequately large, barely, but they've rolled the brims up on the sides to convey a kind of hip jauntiness. Hip jauntiness is not a primary cowboy virtue. Still, it's worth pointing out that the three actors who wear more or less acceptable hats all went on to have careers as the stars of memorable action films, including many Westerns, while those who wear hats that aspire to the condition of the modern fedora did not.

When Eli Wallach and his band of Mexican thieves gallop onto the scene, with their grand and authentic-looking sombreros, your first impulse is to root for them in the battle over the beleaguered peasant village, because they wear the hats of men.

In a Western, wearing clothing that at least approximates the style of the period the film is set in has one great advantage — the film has less of a tendency to date. It always looks classic.

Brynner doesn't give a bad performance in The Magnificent Seven, but he doesn't quite inhabit the Western genre. He has a peculiar regal walk which commentators on the film have often drawn attention to — the walk of an actor who has played the king of Siam a few too many times. It doesn't have the natural, fluid grace of a real cowboy's walk, a real horseman's walk. He also has a Russian accent, which the film tries to sell as a Cajun accent — a preposterous ploy that only draws more attention to its anomalous quality.

His silly little hat becomes a symbol of his unconvincing Western persona — inescapable even when he's not talking or walking. A respectable Western hat would have gone a long way towards reconciling us to that exotic persona.

The same is true of the German actor Horst Buchholz, whose German accent the film tries to sell as Mexican. He has the physical grace of a cowboy, and when he dons a big sombrero for a few scenes he actually looks like a cowboy. At all other times his dainty little hat brands him as an impostor.

What were they thinking?

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

My niece Nora, 14, wrote a report for school on Orson Welles's infamous “War Of the Worlds” radio broadcast. It's really superb — check it out here:

The War Of the Worlds: Essay by Nora Rossi

AN ISAK DINESEN QUOTE FOR TODAY

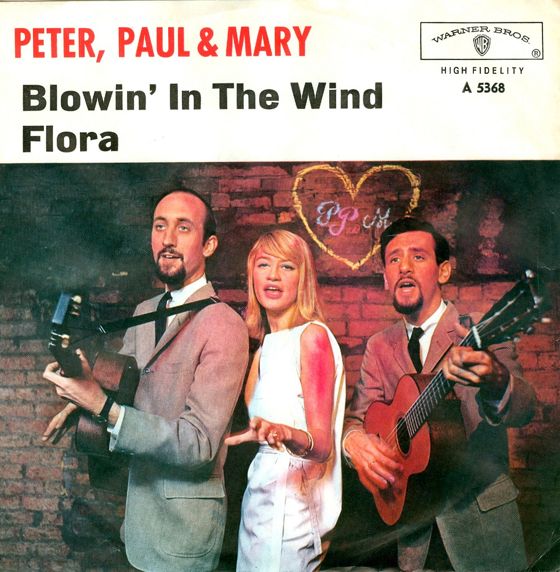

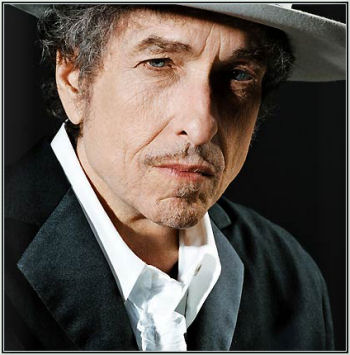

BOB DYLAN

Bob Dylan turns seventy today.

I first heard a Bob Dylan song in the summer of 1963, when I was 13.

It was Peter, Paul and Mary's cover of “Blowin' In the Wind”. Just

about everybody heard that version of the song in the summer of 1963 —

it made it to number 2 on the Billboard charts and got lots of radio

play.

In the Fall of that year I went off to boarding school and a classmate

had brought with him an LP of The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. That was the

first Dylan album I ever heard.

So from the onset of puberty until today, Bob Dylan has been with me. He helped me grow up when I was a teenager, he helped me get

old. He helped me with belief and with unbelief.

Most of all he helped me with the problem of losing things. All of

life is about losing things — loves, innocence, friends, dreams. In

the end, we lose everything, in that pine box for all eternity. And

this is cool — it's what we're here to do. Lose. “The stars are

threshed, as souls are threshed from their husks,” is how William Blake

put it. Dylan said, “Just when you think you've lost everything, you

find out you can always lose a little more.”

The world, especially the modern world, tells us we can have

everything. In truth, we can have nothing, except what's left when

we've lost everything. Dylan sings about what that is, too.

Prophet, wise counselor, mentor, heckler, song and dance man — Bob Dylan has walked beside me every

step of the way through my adult life. Even when I lost sight of

him, he kept up with me, and was there when I needed him. Even when I gave up on him, he never gave up on me. “You might need this song someday,” he's always said, “so here it is.”

I know he would not want any thanks for this — the gifts he had to

give weren't his. He found them somewhere, and passed them along. He

never got adjusted to this world, and has reminded me that I shouldn't

get adjusted to it either. We've got business elsewhere.

SOMETIMES IT'S NICE

. . . to think about Françoise Dorléac.

[Image courtesy of Facebook friend Farran Smith Nehme.]

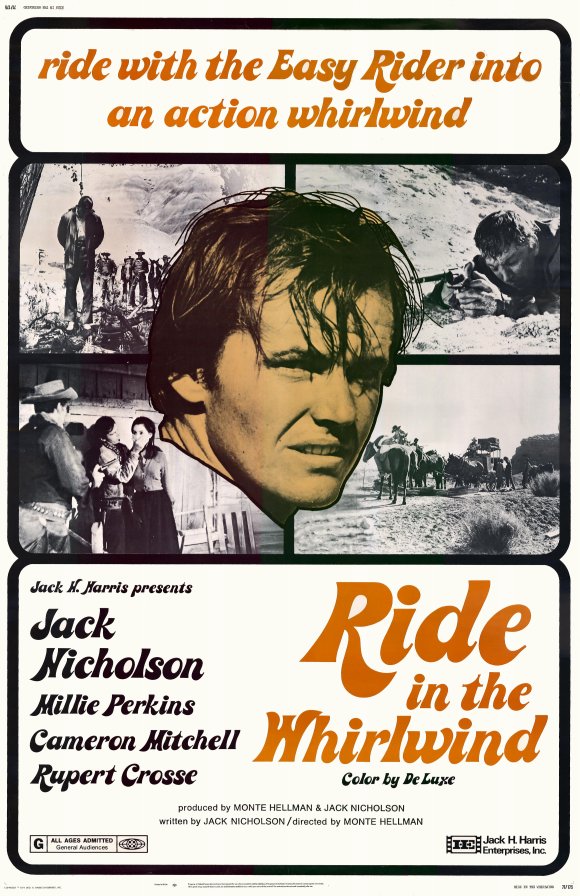

A WESTERN MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

This is a poster from a 1971 re-release of the film, orginally made in 1965. The tag line of course references Easy Rider, released in 1969, which had made Nicholson a marketable personality. The film was financed by Roger Corman and made back-to-back with another Hellman Western, The Shooting, near Kanab, Utah. The films were then sold to a distributor who sold them directly to television. Ride In the Whirlwind was subsequently released theatrically on a couple of occasions and became a huge hit in France, especially among cinéastes there, who have lionized Hellman ever since.