EULOGY FOR OSCAR

Oscar Fruchtman died on the morning of Saturday, March 28, 2009 in his

apartment at the Kenmore Residence on East 23rd Street in Manhattan.

This eulogy was given on Monday, March 30, 2009 at the Plaza Jewish

Community Chapel, 630 Amsterdam Ave. Previous speakers at the service

were Rabbi Emeritus David H. Lincoln and Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove, both of

the Park Avenue Synagogue.

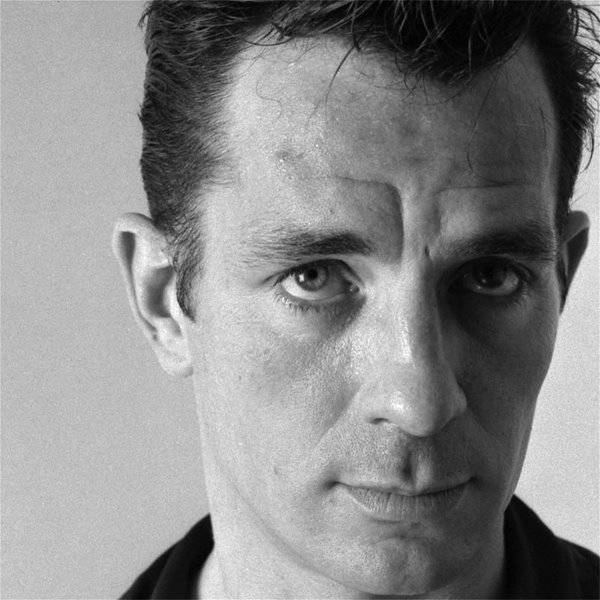

My name is Hugh McCarten and I was Oscar’s longest serving friend. I

was his best friend. Rabbi Lincoln said we should always be prepared

for circumstances like this, but I wasn’t prepared when Oscar passed

away on Friday [from the audience, Janet Moss, Oscar’s mother:

“Saturday!”] Oh, right – Saturday. And I’m not prepared for what I’m

doing now, but as Oscar’s dad Carl used to say, “These are the knishes

that prevail.” So we’re going to go ahead. The topic is remembering

Oscar and I’m trying to think of the best way to do that. Rabbi

Cosgrove suggested that perhaps Oscar, following Talmudic tradition,

was one of the “Lamed Vovniks”, 36 righteous individuals who are on the

earth at any given time and without whose divine presence the world

could not endure. That’s possible, but I came across a word recently

that I am sure applies to Oscar and the word is “luftmensch”, literally

an “air man”, a dreamer.

And apparently Oscar was a dreamer from the beginning. I first got to

know him and his wonderful family back in the early 1970s and he told

me that practically his first memory was of his parents' liquor store,

South Ferry Liquors. As a young child, he said he couldn’t quite

understand what “South Ferry Liquors” meant and thus he envisioned some

kind of fantastic combination boat/store that went careening around the

New York harbor. And so began his dreaming . . .

He told me he had been named after his grandfather, whose spirit it was

suggested he had inherited, and he told me about his grandmother Sadie,

who liked to invoke the 11th Commandment: “Don’t Get Caught!” And about

his Uncle Louie who died in 1957 at Yankee Stadium in the middle of a

New York Giants football game and about growing up in Brooklyn on

Ovington Avenue and later on Eastern Parkway. He told me about going to

Stuyvesant High School and becoming the International President of USY

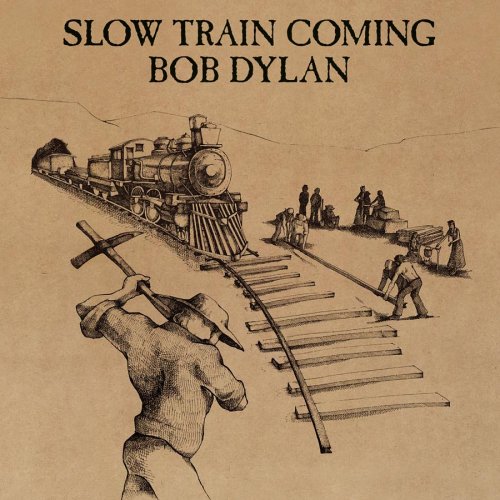

– United Synagogue Youth. Oscar was, as some of you know, a great

songwriter and I wish I could sing a bunch of his songs today, but we

don’t have time, so I’d like to read the lyrics of a song written in

the 1970s that sums up his youth and its title is “Brooklyn Boy”:

BROOKLYN BOY

I don’t say much but I’m a fast talker

I never look I’m a jay-walker

I guess you could say I’m a New Yawker

I’m just a Brooklyn Boy

From Flatbush to Brooklyn Heights

You better not miss those Brooklyn sights

Botanical Gardens and Prospect Park

But you better lock your door when it gets dark

I used to root for the Brooklyn Dodgers

Duke Snider, Pee Wee Reese, the late Gil Hodges

I used to love to watch Roy Rogers

I’m just a Brooklyn Boy

Coney Island, down by the sea

I just hop right on that BMT

Mom cooled Pepsi right in the fridge

And Daddy tried to sell the Brooklyn Bridge!

I used to eat in a delicatessen

Turkey on club with Russian dressing

Then I would take my piano lesson

I’m just a Brooklyn Boy

I’m just a B-r-o-o-k-l-y-n

I’ll probably sing it once again

I’m just a B-r-o-o-k-l-y-n

Brooklyn Boy

(Music and lyrics by O. Fruchtman)

(©2010 A. Fruchtman)

[Here's a link to Oscar performing the song live — “Brooklyn Boy” .]

Then the Brooklyn Boy went to Princeton and after appearing in some

Triangle Club shows there, he started making his way in the showbiz

world.

He began playing the guitar and singing with Princeton classmate and friend Ed

(Woody) Allen and later I joined the two of them and we formed a band –

Oscar and The League Of Weenies. In 1974 we became the first band ever

hired to play at the club CBGB and two weeks later we were the first band

ever fired from playing at CBGB. All through the early and mid-70s

Oscar was hanging around some of the most creative people on the New

York scene, especially the folks involved in the early years of the TV

show Saturday Night Live. At one point Michael O’Donoghue, the head

writer for the show said,” You know, all Oscar needs is a little

success.” But Oscar never found any real commercial success and at

crucial moments he seemed to have a special knack for sabotaging his

opportunities and, frankly, manipulating and ultimately alienating

people. I asked him once about this tendency and he said, ”Well, you

know my motto – I’ll burn that bridge when I get to it.” And so – he

did!

And he turned away from the traditional path and became his own

creative universe. He was a poet, a singer and songwriter, a street

performer, a painter, a collagist . . . A message from Oscar on your

answering machine might be a miniature masterpiece. I’m now holding up

a business card he had made up for a fictional concern located on

Medford Avenue in Fairlawn, N.J. And the outfit is called: “Mind Your

Own Business!“ and their slogan is “Don’t Call Us and We Won’t Call

You!”.

You didn’t hear Oscar on the radio or see him on TV, but the whole

world was his canvas. And he travelled with a mission. He was seeking

the essential humorous truth of life. And this was his exacting

discipline: He was the master of taking any situation, finding the

precise comic center and putting it into words – words that made you

laugh. In my opinion he was quite simply the funniest person ever. Nor

did it matter if he was the butt of the joke – what was paramount was

the comic truth. And he filled his memorable songs with humor and they

overflow with warmth and humanity.

So this was a brief attempt to take the measure of my friend Oscar

Fruchtman. He was a luftmensch who had enough adventures and burnt

enough bridges for several lifetimes. He loved his family, he loved his

friends, he loved his music and, above all, he loved to create

laughter, that rarest ability and his special gift to all. Oscar, you

did a lot of surprising things in your life, but what you did on

Saturday surprised me the most. And Janet and Annie and Peter and I

will never forget you, because you are unforgettable. And we are so

proud we had the chance to share your time on earth.

Rabbi Cosgrove said he was going to pull on his earlobe if I was

talking too long and he hasn’t done that yet, so I’m going to get out

my guitar and sing a song Oscar and I wrote – it’s mostly Oscar, but I

contributed a little.

(While getting set up, I took a swig from a bottle of Poland Spring

[from the audience, Janet Moss, Oscar’s mom, “Drinking on the job!”])

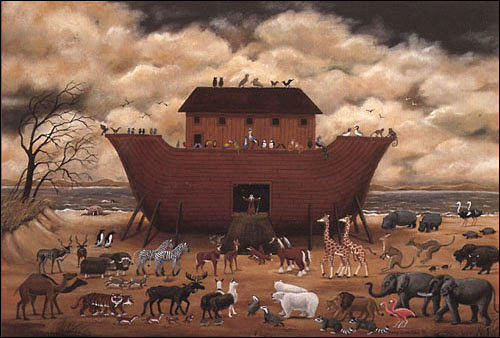

This song is very appropriate for this setting and you’ll hear why.

It’s called “Floating Away” . . .

FLOATING AWAY

‘Twas the night that Noah went crazy

And he started to talk about building a boat

'Twas the night that Noah went crazy

And he started to talk about floating away

Floating Away – I don’t care what the people say

For I’ll be floating away, waiting for the break of day

Everybody laughed when he talked about building his craft and floating

He talked about taking two of each kind

He talked about leaving it all behind

And he grabbed his hat and he grabbed his coat

And he mumbled something about floating away

Floating Away – I don’t care what the people say

For I’ll be floating away, waiting for the break of day

Hey, what’s with Noah? If he don’t move that ark they’re going to tow

it away

But he just ripped up the ticket and he stowed it away

Cause he’s soon to be floating away

Floating Away – I don’t care what the people say

For I’ll be floating away, waiting for the break of day

First there came the wind – I hope he’ll let us in

Then there came the rain, maybe Noah’s not insane!

‘Twas the night that Noah went crazy

And he started to talk about building a boat

'Twas the night that Noah went crazy

And he started to talk about floating away

For forty days it rained then the sky was clear and the land was dry

And the bird of peace flew by and Noah got high

And again he was floating away

Floating Away – I don’t care what the people say

For I’ll be floating away, waiting for the break of day

(Music by Oscar Fruchtman/Lyrics by Oscar Fruchtman and Hugh McCarten)

(©2010 A. Fruchtman/H. McCarten)