There's

now a button in the column to the left (Film Reviews A-Z) which will

take you to a list of all the movies reviewed on the site and allow you

to link to them directly.

FILMS REVIEWED

Amarilly Of Clothesline Alley

Apocalypto

Baby Face

The Bad and the Beautiful

The Bellboy

The Big Combo

The Big Trail

The Birds

Blind Husbands

Born Reckless

Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garcia

Casablanca

Cherry 2000

Cheyenne Autumn

Chimes At Midnight (Falstaff)

Chinatown

Citizen Kane

City Girl

The Civil War

The Clock

The Conformist

Contraband

Crime Wave

Daisy Kenyon

The Dark Corner

Diamonds Are Forever

Double Indemnity

Dracula (1931)

The Dreamers

El Cid

Electric Edwardians (DVD Collection)

Eternal Sunshine Of the Spotless Mind

Eyes Wide Shut

Falstaff (Chimes At Midnight)

Flesh and the Devil

Force Of Evil

Four Sons

G. I. Blues

The Garden Of Eden

The Ghost and Mrs. Muir

The Girl Can’t Help It

The Glass Bottom Boat

The Great K & A Train Robbery

Hangman’s House

He Who Gets Slapped

Headin’ Home

How Green Was My Valley

The Hunchback Of Notre Dame (1923)

I Confess/The Wrong Man

Intolerance

The Iron Horse

It’s All True

Just Pals

King Kong (2005)

The Ladies Man (1961)

Laugh, Clown, Laugh

Laura

Lawrence Of Arabia

Leap Year

Leave Her To Heaven

The Lord Of the Rings

Loving You

The Marriage Circle

The Married Virgin

Merry-Go-Round

Miss Lulu Bette/Why Change Your Wife?

Mr. Arkadin (Confidential Report)

My Best Girl

1900

Nosferatu (1922)

Odds Against Tomorrow

On Dangerous Ground

Out Of the Past

The Oyster Princess

Pandora’s Box

The Penalty

Peter Pan (1924)

Pilgrimage

Pitfall

Sadie Thompson (1928)

Saved

Scarlet Street

Seas Beneath

The Set-Up

Shadow Of A Doubt

The Shop Around the Corner

Show People

Spider-Man 2

Summer Magic

Sumurun

The Sundowners

They Live By Night

3 Bad Men

The Three Burials Of Melquiades Estrada

Titanic

Tobacco Road

Trapped

Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1927)

Up the River

Vertigo

Vicky Cristina Barcelona

War Of the Worlds (2005)

The Way Of Peace (Frank Tashlin Short)

What Time Is It There?

Why Change Your Wife?/Miss Lulu Bette

Why Worry?

The World Moves On

The Wrong Man/I Confess

THE FILM NOIR CANON

People who love film noir also love to argue about what films belong in the category and what films don't. They compile lists of films noirs and break them down into subcategories. The general drift of this activity is to call almost any film noir

as long as it was made in Hollywood in the 1940s or 1950s, in black

and white, and features moody lighting, cynical attitudes and

some content related to crime.

This inclusiveness is abetted by studio home video departments, which will designate any film with the above attributes a film noir because the label is sexy and apparently helps sell DVDs.

In the process, the term gets so vague as to be useless. I would

argue that there is a core set of films that are truly and uniquely noir,

reflecting a particular time in America, with a particular mind-set, a

mood of existential dread that seemed to invade the American psyche

after the end of WWII, at the beginning of the atomic age.

This sense of dread was in the air before then, of course, as the world

hurtled towards war. It can be felt very clearly in some dark

films made during the war — in Hitchcock's Shadow Of A Doubt, in Wilder's Double Indemnity, in Huston's The Maltese Falcon. The first two of those films, along with Leave Her To Heaven, fall into a distinct category of their own — the domestic noir.

The Maltese Falcon seems on its surface to belong to another distinct category, the hardboiled detective thriller, which had noirish

elements but whose essentially noble protagonist rescued it from

existential dread. Yet Bogart's Sam Spade seems to be losing

faith in the nobility of his code, to see it as meaningless, and I

think that fact alone allows one to call The Maltese Falcon a true film noir. Just compare Bogart's Spade to his Phillip Marlowe in The Big Sleep, which plays like a hardboiled romantic comedy by comparison with Huston's film.

The point about The Maltese Falcon can be argued, of course, and I place it among the true films noirs with that reservation in mind. Here are some of the other films I think of as truly noir, without such reservations:

Out Of the Past

The Killers

His Kind Of Woman

The Dark Corner

The Set-Up

Gun Crazy

Fallen Angel

Angel Face

Touch Of Evil

Detour

The Wrong Man

Criss Cross

The Killing

In A Lonely Place

On Dangerous Ground

Crossfire

Where the Sidewalk Ends

Brute Force

The Sweet Smell Of Success

Night and the City

Thieves Highway

The Lady From Shanghai

14 Hours

The Long Night

Nightmare Alley

Odds Against Tomorrow

Act Of Violence

Crime Wave

They Live By Night

Decoy

The Big Steal

Side Street

Where Danger Lives

Tension

Kansas City Confidential

The Big Combo

Gilda

Note that not all of these films end badly for the protagonist, and not all of them feature femmes fatales — several actually have femmes

that rescue the protagonist, and in one of them the protagonist is

rescued, just as improbably, by Jesus. But in all of them the

protagonist needs rescuing, in all of them he's lost in a nightmare world that's

existentially different from the world that existed before WWII and he can't, by his own efforts, get out of it.

Even a film like His Kind Of Woman, which goofs comically on this world, is also recognizing it.

In future posts I'll list some of the films commonly called noir

which I don't think really are, because, though they may reflect to one

degree or another the same existential dread as the true noir,

they don't acknowledge it as a profound and inescapable condition.

It's almost a spiritual distinction, and therefore hard to

define precisely, but I think it's one worth making.

A BOUGUEREAU FOR TODAY

Bouguereau’s figures are so solid that when he sets them floating in the air the effect is unsettling, uncanny, but in a pleasant way, as flying in dreams is pleasant.

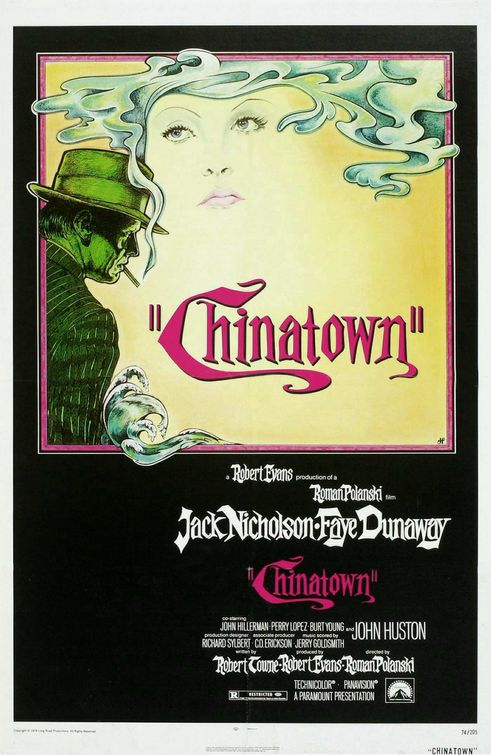

CHINATOWN

Chinatown is one of the few neo-noirs that really lives up to the designation. Its view of the world is truly bleak — a moral maze from which there is no escape. As with many films noirs there’s an indictment of the political system but also a sense that corruption

is universal, not limited to any one class. It’s an existential corruption.

The big difference between Chinatown and the classic post-WWII noirs is one of gender perspective. The post-war noirs were centrally concerned with male anxieties, with the way the world looked from the point of view of a suddenly inauthentic and insecure

manhood. In them, a man might be ruined by a powerful female, a traditional femme fatale, or he might be saved by good woman, but in both cases the situation was beyond his control. Chinatown finally took a look through the other end of the telescope, imagining what the general collapse of manhood might mean for women.

As screenwriter Robert Towne has said, Evelyn Mulwray is the only

character in the film who operates out of purely decent motives, trying

to rescue herself and her daughter from the clutches of a rancid,

decayed patriarchy. The protagonist of the film, private eye

Jake Gittes, is a decent enough fellow but impotent when it comes to

helping, much less saving, her.

We’re not quite dealing with a feminist perspective here — we’re still

looking at the mess from a male viewpoint, assessing the male’s failure

of responsibility rather than exploring the female’s search for empowerment —

but we’re a long way from the phallocentric cry of male bewilderment and pain that

was at the heart of film noir.

Still, the deconstruction of the traditional femme fatale

is very thorough and deliberate, because Evelyn Mulwray is first

presented as a kind of spider woman, with all the generic clues that

used to alert us to the fact that the woman in question was going to be

trouble . . . and that’s how Gittes constructs her. The big

switcheroo is that Evelyn is in much more trouble than she has the

capacity to cause anyone else, that it’s her father’s fault and that

Gittes isn’t smart enough or strong enough to deliver her from it.

Towne’s conversation with the noir tradition is very elegant and profound. He goes back, in the film, to 1937, to the hardboiled detective fiction out of which film noir mutated, and deconstructs the “tarnished knight” of that form, locating in him the existential nullity of the film noir protagonist. Gittes has Phillip Marlowe’s private code of nobility, his commitment to a kind of rough justice, but it’s not enough anymore. The only real nobility he has left is his ability to recognize the cost of his own impotence.

When his associate speaks the film’s famous last line to him, “Forget

it, Jake — it’s Chinatown,” we know he won’t, we know he can’t.

He lives there now — and somehow, because of his failure, we all do.

A NORMAN ROCKWELL FOR TODAY

America is at war right now but you'd never know it from any kind of

personal experience, unless you're serving in the military or know

someone who is. Most of us

are asked to make no sacrifice, there is no meaningful national debate

about the war's prosecution or aims — just a lot of

ideological posturing, on both ends of the political spectrum.

With a volunteer army,

aided by thousands of private mercenaries, there is no direct pressure

on the nation as a nation to come to terms with what's happening.

They are fighting the war for us, unless they happen to be our own sons, daughters, fathers, mothers, husbands, wives.

Whatever you think of the war, I think you have to admit that the

current administration has committed the one unforgivable sin for the

leadership of a democracy — sending soldiers into a war without the

broad commitment of the nation behind them. Any war that we, the people, don't fight together is bound to turn into a bad one and very likely into a losing one.

Look at the image above by Norman Rockwell, from a Saturday Evening Post

cover. The young soldier, obviously just back from the Pacific

Theater, is a Marine. Viewers of the time would know that he most

likely is just back from Hell, from Iwo Jima or Peleliu or Okinawa — that he has

participated in unimaginable horrors. There is no glimmer of

triumph or satisfaction in his face, just a sense of awe, of almost

bewildered hardness. The folks who make up his audience seem to

appreciate, even if there's no way they could possibly understand,

what's he just done for them, and one thing he's just done for them is

separate himself from their world irrevocably, forever.

They seem to comprehend this — they all seem suffused with the gravity of it, they all seem to take responsibility for it.

This is so far beyond catchphrases like “We support our troops.”

The image reflects a moral complexity, a moral tenderness, that only art can evoke — an

ideal of citizenship that seems to have vanished from our democracy.

MALE ANXIETY AND FILM NOIR

The anxious, existentially befuddled male is at the heart of film noir.

Caught in a trap that’s not always of his own making, but almost always

worse than he deserves, he stumbles around in a maze with no

exit. Sometimes he’s destroyed by a powerful female, against whom

he has no defenses, sometimes he’s saved by a powerful female operating

out of unaccountable charity. In either case, the situation is

ultimately out of his control, which on some level makes each type of

female equally threatening.

Some people have located the source of this paradigm for male anxiety in the new economic status women achieved by entering the

workforce in large numbers during WWII, but this is a very superficial

explanation for the mythology of noir. Eddie Muller, probably the best and certainly the most entertaining commentator on film noir, points out that the good girls of the tradition are almost always working girls, while the femmes fatales are almost always looking to get something for nothing, and certainly not a paycheck for an honest day’s work.

The male anxiety embodied in the tradition clearly derives from a

deeper source — the moral discombobulation of war itself, the

spiritual exhaustion this particular conflict induced, and the

inconceivable fact of the atomic bomb which raised moral issues and

created fears that the human psyche was ill-prepared to engage.

The ravaged psyches of Americans in the aftermath of a “good war”, a good war they won, so vividly explored in film noir, in some ways says more about the nature of all wars than any works of art which dealt with the conflict itself.

ELVIS FOOD

Admit it — sometimes you just get a taste for Elvis food, for the stuff he really loved, like banana cream pie. Tucking into an oversized slice of banana cream pie you can almost feel what it must have been like to be a bloated, drug-addled cultural icon and genius on the road to destruction, and sense Elvis’s own childlike bewilderment at it all.

Incidentally, if you live near a Marie Callendar’s, as I do, try their banana cream pie, which tastes old-fashioned somehow, like a pie you’d get served at a 50s-era lunch counter or school cafeteria. I just know Elvis would have approved.

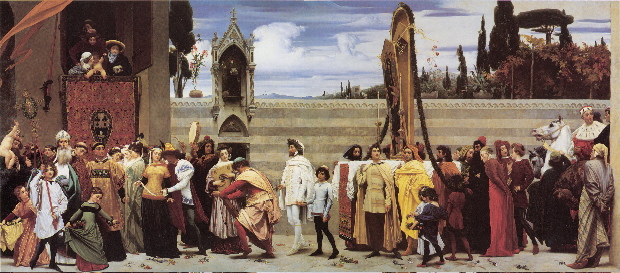

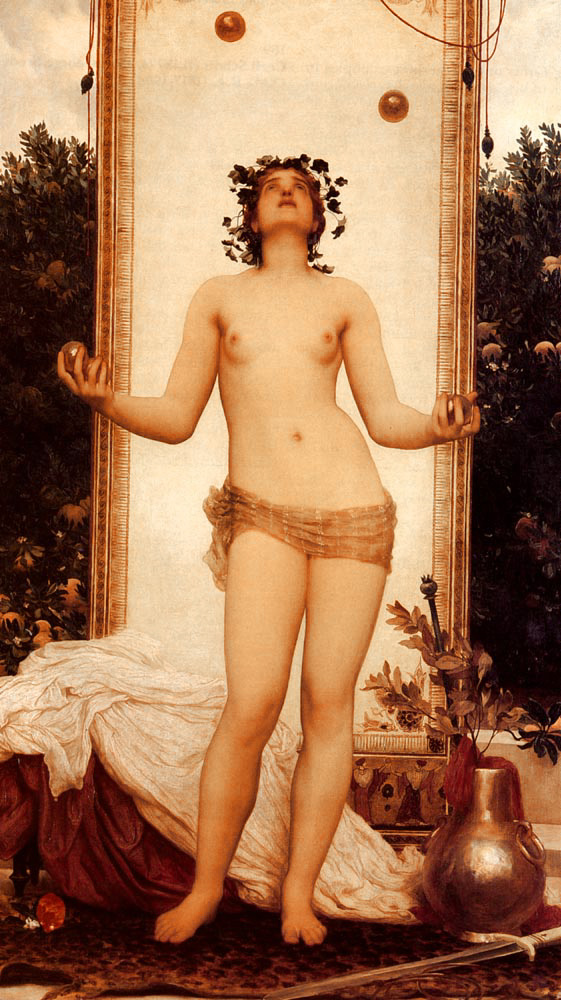

LORD LEIGHTON: A VICTORIAN ARTIST YOU SHOULD KNOW

Lord Leighton was generally considered the dean of Victorian academic painters.

He combined the decorative stylization of the early Pre-Raphaelites with a more photo-realistic draftsmanship, an approach which made his work popular with a wide public and influential among his fellow painters.

The painting above, exhibited in 1855, caused a sensation and

established his reputation. An enormous, 17-foot-long work

depicting a procession in Renaissance Italy, it was admired by Queen

Victoria, who bought it.

Leighton also did works in a style that might be called magical

photorealism, like the one below, which reminds one of similar images

by Bouguereau:

He could also, like Bouguereau, be frankly sensual in a more naturalistic mode:

Like Alma-Tadema he did vexing evocations of the ancient world:

His historical paintings could have strong narrative and theatrical qualities, like this one, Dante In Exile:

On top of all that he produced some fine portraits, like this famous image of the explorer Sir Richard Burton:

All around, Leighton was really cool.

A VINTAGE CELL-PHONE PHOTOGRAPH FOR TODAY

Jae Song and my (then) new High-Fashion Glamour Doll of Enid, from Ghost World — a photograph taken in New York a few years ago with my cell phone

camera.

BLUE TROUT

Sometimes after a long day of writing my mind is gripped by strange ideas about food — strange in the sense that they don’t involve Swiss cheese and crackers or peanut butter sandwiches or frozen meatloaf dinners.

One day, as it happened, I was reading a piece by Mr. Ernest Hemingway about trout fishing in Europe. In it he described a method of cooking trout he had encountered in Switzerland at rural inns. It involved boiling the trout until it turned blue in a liquor made of water, white wine vinegar, bay leaves and red pepper — not too much of any ingredient in the water, says Mr. Hemingway, without further elaboration.

This is not the blue trout described by M. F. K. Fisher, which involves placing the trout live into boiling water, unless the Swiss innkeepers were holding out on Mr. Hemingway, but it sounded fine.

I remembered that my local supermarket sometimes offers fresh

rainbow trout, so I headed over there late at night and found one

handsome specimen in the fish department. I brought it home, filled up

a large pot with water — it was a large trout — emptied about six

ounces of white wine vinegar into the water, added six fragrant bay

leaves and a light sprinkling of cayenne pepper, and set it all to

boil. When it was bubbling I slipped the fish in.

I turned the heat down and simmered the trout for about fifteen minutes. In

fully boiling water, ten or less would have been more than sufficient. I

tested the fish using a method recommended by an old edition of The

Joy Of Cooking — which is to separate the meat from the bone of the

spine at the thickest middle section of the fish. When the meat there

is tender but no longer translucent, the fish is done.

I ate the fish with drawn butter, as Mr. Hemingway says the Swiss did. “They drink the clear Sion wine when they eat it,” adds Mr. Hemingway, but they don’t depend on the beverage department of a supermarket for their wine. I made do with a perfectly respectable Pinot Grigio by Bolla, cheap, dry and light. I keep looking for the clear Sion wine, though — Sion, pictured below, is the primary wine-producing region of Switzerland:

Even without the Swiss wine, the result was a meal of almost unimaginable delicacy. Trout is delicate anyway, and the light seasonings in the water only emphasized the subtlety of its taste. It all resonated on the tongue like a memory of food — insubstantial and fleeting.

WHAT IS REFRIGERATOR ELVIS WEARING TODAY?

Just his bathing suit at the moment — he looks ready for some summertime Vegas poolside fun!

NOIR AND EXISTENTIALISM

Tony D'Ambra, on his informative films noir

web log, questions my recent post on The Genealogy Of Noir for not paying sufficient attention to the influence of European Existentialism on the

style. I think he's got a valid point here, though the subject is

complicated. Existentialism itself was influenced by Poe, via

Baudelaire, and Hemingway's proto-existentialism, expressed most purely

in his early short stories, directly influenced film noir — and of course these short stories preceded the seminal writings of Sartre and Camus.

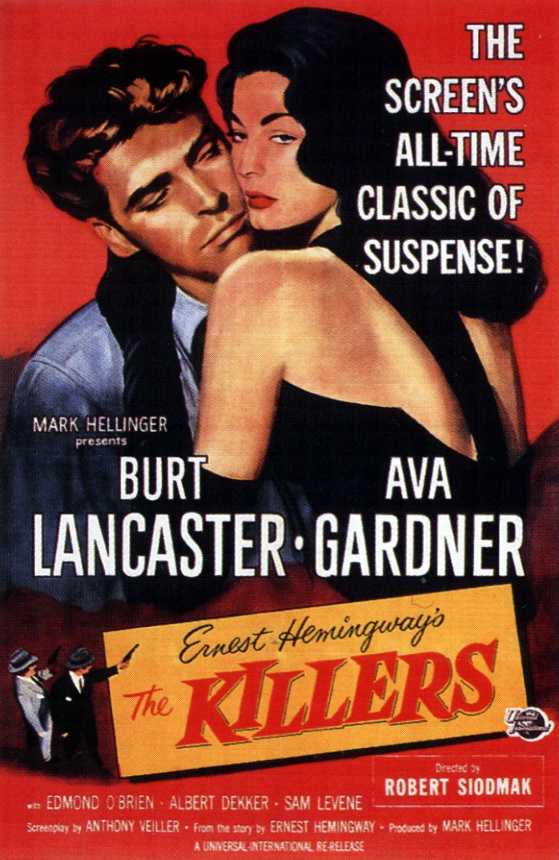

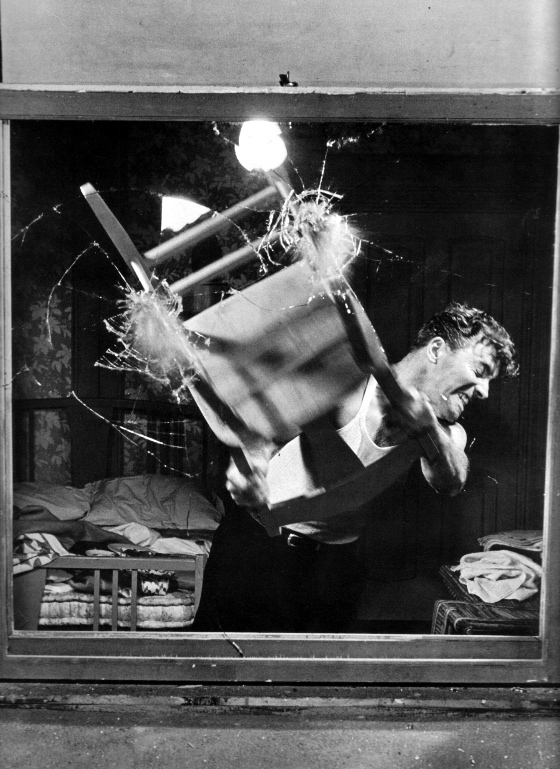

The influence of Hemingway on noir is of course most distinct in Robert Siodmak's The Killers,

based on the Hemingway story. The story was published in 1927 and

reflected a bleak view of human virtue, which is shown to consist

largely of facing death with stoic conviction. This decidedly

unromantic attitude was clearly a product of Hemingway's experiences in

WWI, and resonated precisely with the mood of the generation which had

just fought a second world war.

We can't see the existential dread that informs film noir as simply a product of Europe, an import, even though, as D'Ambra points out, many of the crucial filmmakers in the noir tradition were refugees from the European catastrophes of

the 30s and 40s. This view wouldn't explain the extraordinary

popularity of the form with American audiences for almost two

decades. Film noir must

have reflected anxieties buried deep in the post-war American psyche,

aroused by the sheer horrific spectacle of total war on a global scale

and by the unthinkable reality of the atomic bomb.

Although Siodmak's film softens Hemingway's story by giving us a

positive, resourceful guide through the moral maze that ultimately

destroys the Swede, the film approaches the condition of pure noir

because Lancaster's Swede is the star part in the picture — it's his

bleak fate we identify with, not that of the successful insurance

investigator played by Edmund O'Brien.

Lancaster, after all, is the one who gets to put his arms around

Ava Gardner, for which going to Hell seems a small enough price to pay

— and once you start thinking in those terms, you're already caught up

hopelessly in the maze of the noir's dark city.

COKE FLAG

I painted the image above on the wall of a farmhouse in Vermont

sometime in the late Sixties. For some reason the owners of the

farmhouse decided not to paint over it and so it has survived for going

on 40 years, as I just discovered via this photograph of it, taken by a

friend last Sunday when he was visiting the place.

The design is kind of cool, even if the draftsmanship leaves something

to be desired. It still sums up what the Sixties felt like to me

at the time, when the idea of being patrotic about American culture

made more sense than being patriotic about the American state.

CASABLANCA: THE ACTRESS AS AUTEUR

Casablanca

is a genuinely miraculous film, one of the few Hollywood masterpieces

that really was created by committee. The script incorporated the

work of six principle writers, who had lots of editorial

supervision. One of the film's most memorable lines, “Here's

looking at you, kid,” was reportedly contributed during filming by the

actor who spoke it, Humphrey Bogart, and supervising producer Hal B.

Wallis wrote the famous last line, “Louie, I think this is the

beginning of a beautiful friendship”, which was added as a wild line

after principal photography ended.

If the film has a nominal auteur

it would have to be Wallis, who organized the collective that made the

film and generally had the last word on what became part of the final

product. Jack Warner, the head of the studio, made only one

creative suggestion — to cast George Raft in the Bogart role, an idea

that would have made the film the instantly forgettable potboiler it

might easily have become. Wallis talked Warner out of the idea,

but he had some bad ideas of his own, including turning Sam into a

female African-American — but Wallis himself got talked out of these ideas in

turn.

The film's director, Michael Curtiz, was known as a great “director of

scenes”, with a sure sense of pacing, but he spoke English badly and

apparently had no sense of story construction. It was Wallis who

“constructed” Casablanca.

One of the delights of the film is its multifaceted quality. The

play it's based on provides the milieu of the story and some of its

dramatic highlights, but has none of the elements that make the film an

enduring classic. The screenwriting Epstein brothers provided

most of the witty dialogue and writer Howard Koch pushed its political themes

to the fore, but I would argue that it was another writer, Casey Robinson, who didn't

receive credit, who supplied the glue that made Casablanca cohere.

It was Robinson who wrote the principal love scenes between Bogart and

Bergman, developing Bergman's character into the emotional center of

the film. He gave Bergman the opportunity to supply the film with

its heart. Without Bergman's performance the film would be

nothing more than a diverting programmer with an admirable “message”.

The sheer acting craft on display in Casablanca

is stunning, but most of it is just that — craft. Bergman brings

an emotional commitment to her role that's of a different order.

She suggests an inner life that is mysterious, complex, fully

rounded. It's through her eyes that Bogart becomes sexy, that

Henreid becomes admirable, that the dangers of Casablanca become real.

The film's narrative promises much in the way of romance and intrigue and

adventure, but Bergman is all those promises fulfilled. Audiences

loved Bogart and accepted him as a romantic leading man because he held his

own with Bergman in this film, tried to expose himself to her

emotionally on her level and often enough succeeded. Study his expression, his eyes,

in the very brief close-up of Bogart taking his last look at Bergman's

face on the airfield — it's devastating, a moment of total

exposure. By the same token, we recoil at Henreid's Victor Lazlo

because he never opens himself to Ilsa, because he stands on idealism

and form even when gazing into her miraculous eyes.

Roger Ebert has pointed out how Bergman could paint an actor's face

with her eyes — we can see her trying to penetrate his being, and in

the process she gives him being. It's the alchemy of romantic love incarnated. We instinctively despise any

leading man who doesn't treasure her for this, we instinctively admire any leading man who does.

The ending of Casablanca is

morally thrilling, glamorizing virtue and sacrifice, but it would be

little more than a literary gesture without Bergman's presence, without

Bogart's appreciation of her presence. His sacrifice of it breaks

our hearts over and over again because we feel it as our own

sacrifice. By that point in the film she's become every great love that anybody has ever lost and

we hate to see her go — always have, always will. Ingrid Bergman

is the true author of the miracle of Casablanca.