“I’m an occational drinker, the kind of guy who goes out for a beer and wakes up in Singapore with a full beard.”

“I’m an occational drinker, the kind of guy who goes out for a beer and wakes up in Singapore with a full beard.”

American Gothic

In the broadest perspective, film noir belongs in the long tradition of American Gothic fiction, that dark vision crystallized in the tales of Hawthorne and Poe. A kind of counterbalance or reaction to American optimism, this tradition can have an almost savage quality, as though the decision to explore the shadowy realms of the American psyche has led to a determination to follow that path to its uttermost end, to the absolute limits of nightmare.

D. H. Lawrence saw in this tradition a desire to ritually enact the decay of European culture as a kind of psychic prelude to the birth of a new culture. Leslie Fiedler saw the darkness at the center of so much American art as the product of a stunted manhood, which embraced despair and death because it could not find its way to maturity.

However the tradition is explained, it must on some level reflect the enduring contradiction between America’s ideals and its actions. The nation’s founding document, announcing that all men are created equal, was written by a man who owned slaves. In the gap between a radical, transformative announcement such as this and its author’s actual life, corrosive subconscious anxieties are bound to breed.

The Genre Of the Grotesque

Europe’s own literal effort at self-destruction in WWI, and the anxiety this produced in a nation that both rejected the old world and still looked to it for guidance, led to a curious new genre in American movies, reminiscent of Poe — the genre of the grotesque.

In this genre, grotesque figures, deformed or mutilated, enacted tragic scenarios of revenge against the “normal” world, in a vain attempt to assert a private nobility, a private honor. This genre made a star of Lon Chaney, who specialized in tragic grotesques, and is often read as a precursor to the horror film of the 30s, but it was really something else — a way of dealing with the images of death and disfigurement associated with the Great War, a way of expressing the fear that civilization had been deformed by the conflict. Audiences of the 20s could not help but have associated Chaney’s misshapen characters with the mutilated veterans of the battles in France.

This genre died out with the coming of sound, mutated into the campy Grand Guignol of the classic horror film, but it’s worth noting it here because it represents the same sort of coded response to WWI that the film noir represents to WWII — a way of nursing wounds that nominal “victory” had not healed.

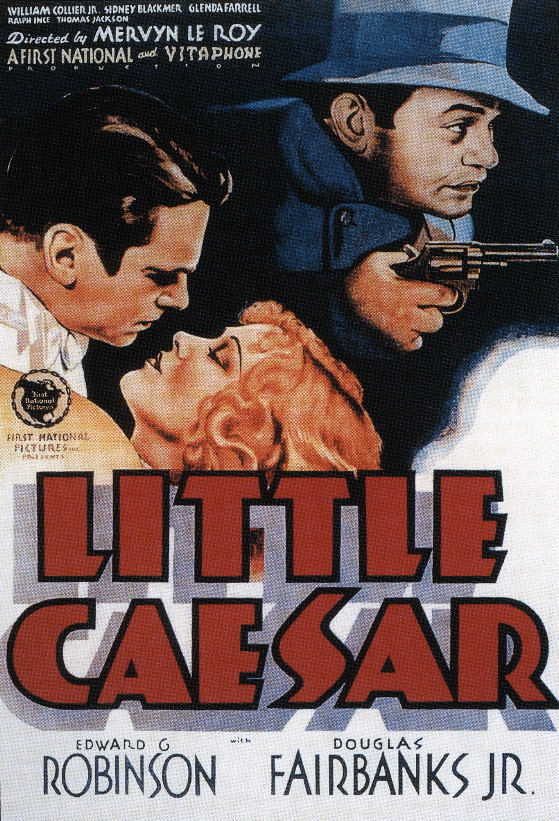

Crime Drama

The underworld crime drama of the 30s was a response to the Depression and to all the social ills it spawned and exposed. It allowed us to enter the underworld of American society — to revel in the destructive rebellion of underworld thugs, expressing a rage against the system felt by many, while still containing them within a conscious code of values which demanded their death, which still posited forces of order and decency which would prevail in the end.

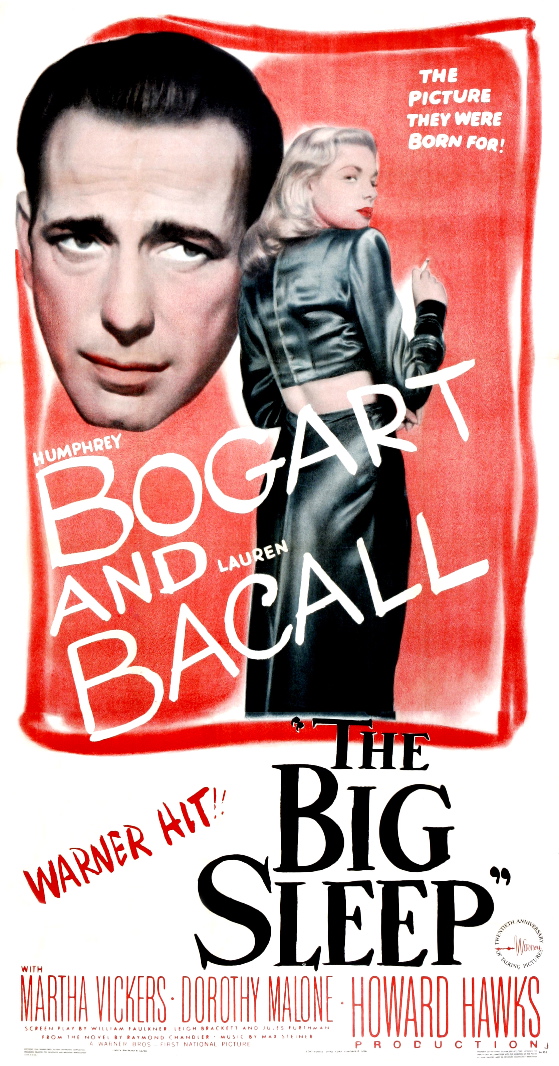

Hardboiled Detective Fiction

A variant on the crime drama was the pulp detective fiction of the 30s and 40s which sent a knight errant into the dark streets, the moral chaos of American life, in search of truth and rough justice. Such fiction most often involved a mystery to be solved, and its solution constituted a triumph over the moral chaos. Pulp detective fiction allowed us to take a brief vacation on the wild side in the company of a guide who was sure to get us home safe again.

Noir

Film noir, as it evolved after 1945, in the wake of a war America participated in fully, sending millions of its young men and women into the fray, and in the wake of the sheer unimaginable fact of the atomic bomb, drew on the traditions of the crime drama and hardboiled detective fiction, but it became something different.

It lost its faith in the forces of order and decency, and in the reliability of its protagonist guides. It posited a moral maze which had no logical solution, no center and no exit points. It

offered the frisson of pure existential dread without an easy cure.

Fiedler’s spiritually stunted males became easy prey to strong women — femmes fatales who could destroy a man at will. (In film noir, a strong woman might just as easily save a collapsed male, but purely as an act of generosity — not because the male deserved saving.)

A protagonist in a true film noir might find himself fated for destruction by a corrupt justice system, by an innocent mistake, by a malevolent coincidence or by some dark inner compulsion which he can’t

control. In all cases, he finds himself in a labyrinth with a compass that has lost its pointer, a thread that runs out short of escape.

Near Noir

There are many films called noir today which don’t really fit the definition offered above. They are variants of the 30s crime drama, docu-noirs like The House On 92nd Street, for example, which may borrow the expressionistic visual style of the true noir but ultimately validate the agents of the state who will set things right in the end. There are also a number of noir-inflected detective mysteries, like Laura, for example, which give us a reliable guide through the moral maze and bring us safely out of it at the end.

This is true even of John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon, the most noir of the classic detective thrillers. Sam Spade does the right thing in the end, rejects the femme fatale

and remains true to his essentially decent code. But he’s more neurotically conflicted about this code than the average hardboiled detective — you get a sense that he’s beginning to suspect it’s all pretty meaningless. In that existential anxiety we see the roots of the true film noir.

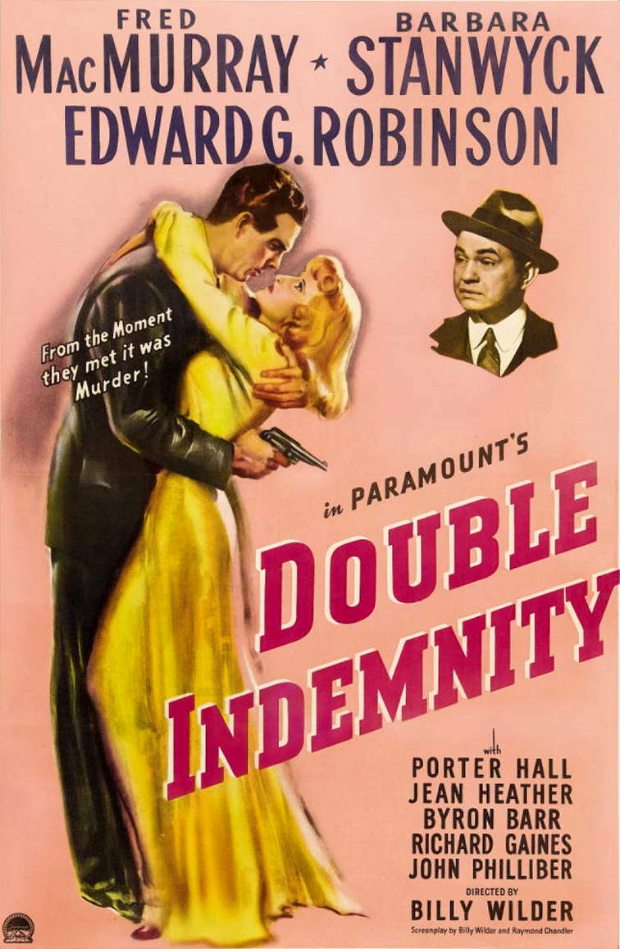

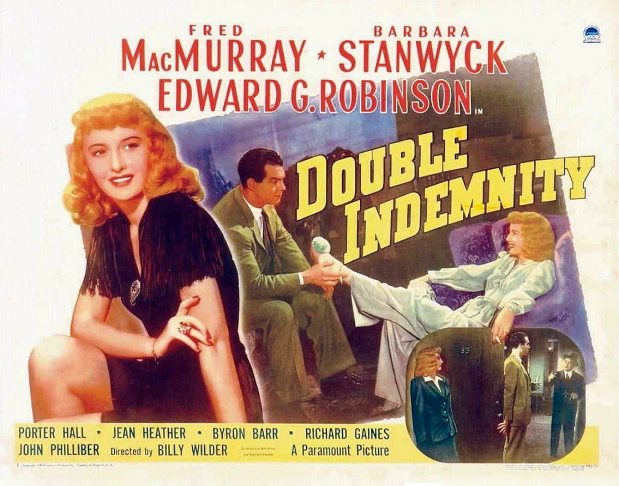

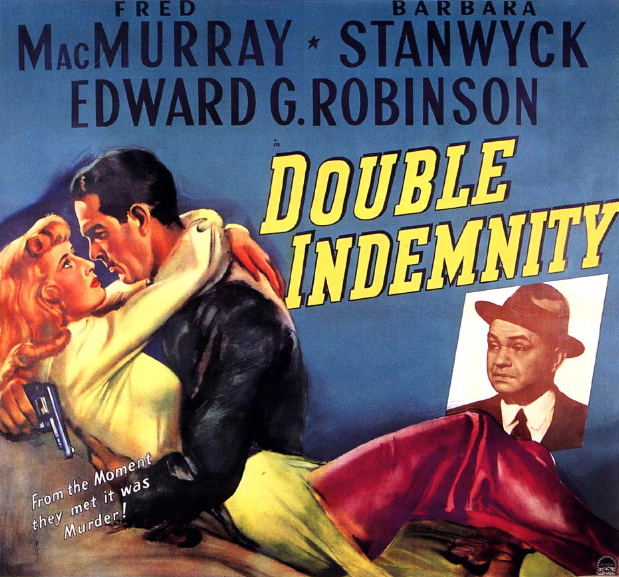

There are, in addition, many films, like Leave Her To Heaven, which explore the existential anxiety of post-WWII America from different perspectives than the true noir. These films — Double Indemnity is another of them — usually offer sociopathic protagonists whom we find both compelling and repulsive, the attitude we had to the underworld thugs of the 30s crime drama, even though their crimes play out in middle-class homes rather than on the mean streets of a city.

True Noir

In the true noir, we can identify totally with the protagonist — not least in his fated doom, or provisional salvation, in a world that has gone terribly wrong, for reasons that aren’t clear and that it probably wouldn’t help much to understand.

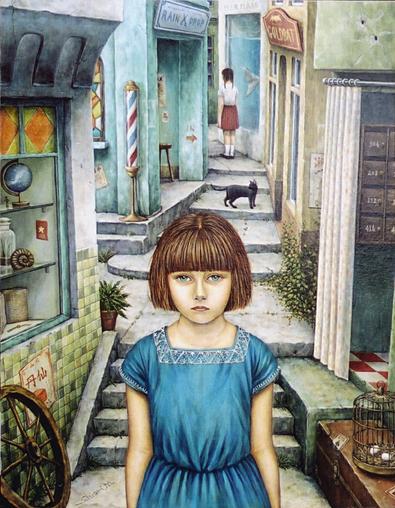

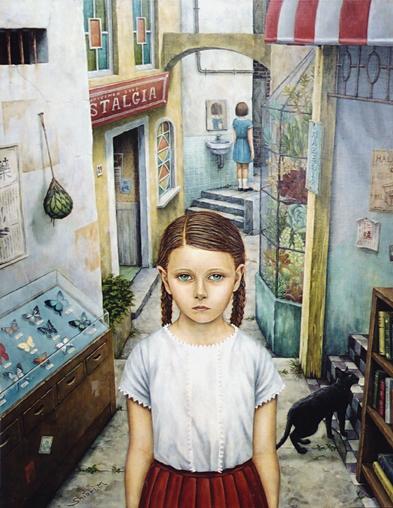

Two lost children by Shiori Matsumoto — lost in a dream space from

which it's almost impossible to escape. Take my advice and don't spend too much time

there . . .

[See more of Matsumoto's dream images here.]

Double Indemnity is generally seen as one of the first (and one of the best) films noirs but I don’t think it fits comfortably into the category. It shares with the true film noir protagonists who are infected with a moral corruption that destroys them. Unlike a true film noir, however, the film doesn’t present this corruption as part of a universal human condition, or as the result of a breakdown of humane values in society as a whole. In the true film noir

the doomed hero is often sped along to destruction by honest mistakes or innocent choices, and just as often is given no course of positive action which would save him. When he makes bad choices they’re frequently motivated by a position of powerlessness in the social order, particularly economic hardship or unjust persecution by the law.

In Double Indemnity, Walter Neff and Phyllis Dietrichson live comfortable lives. Their passion and their greed are not presented as responses to any kind of social oppression, unless it’s the sheer boredom of middle-class life. They’re simply selfish, amoral people.

The film can be read as a critique of middle-class American life, seeing the corruption of the adulterous lovers as a product of the spiritual vacuity of their class, but to me the tone of the film is more peevish and bitchy than political. You get a sense that Chandler and Wilder, who did the adaptation of Cain’s book, hate their bourgeois characters because they’re stupid and tacky — that it’s snobbery that ignites the engine of the narrative. Certainly there’s no sympathy involved and no rage directed at the system which produces such people.

Made during WWII, the film taps into the creeping spiritual malaise and suspicion of civilization, as well as the sense of the existential impotence of men, that would inform the postwar film noir — and it portrays one of the most fatal femmes in the entire history of cinema. But I think these things are mostly the result of coincidence, an intuition about the temper of the times that allowed Chandler and Wilder to indulge what was primarily a personal prejudice against their social and intellectual inferiors. To them, I think, Walter Neff’s biggest crime wasn’t murder — it was his dumb salesman’s jokes and the self-satisfied way he delivered them. Phyllis Dietrichson‘s one unforgivable sin was the cheap blonde wig.

I’m talking here about the philosophical mood of the film, the attitude of the creators, but of course those things are transformed in the film itself, whose dark undertow of suspense and fatal miscalculation is so powerful that it transcends the bitchiness of Wilder and Chandler, evoking an anxiety far deeper than the snob’s fear of bad taste. Double Indemnity, finally, achieves the precise effect of a nightmare, while not venturing into the precise nightmare landscape of the true film noir.

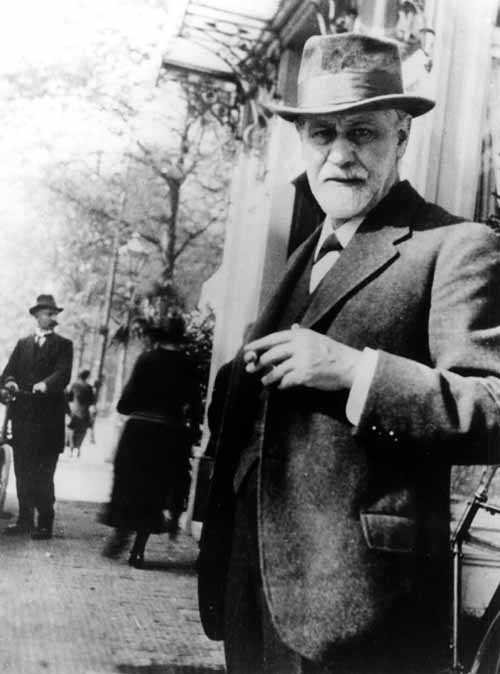

“Some obstacle is necessary to swell the tide of the libido to its height . . . In times during which no obstacles to sexual satisfaction existed, such as, may be, during the decline of the civilizations of antiquity, love became worthless, life became empty, and strong reaction-formations were necessary before the indispensable emotional value of love could be recovered.”

This helps explain why modern American culture is so pornographic on

its surface but so unsexy. It may be the least sexy culture in

the history of civilization. It occurs to me that the attraction

to Victorian style, visible in sub-cultures like steampunk, may be a

nascent reaction-formation to the dead sexuality of modern pop culture.

Would downloading the Paris Hilton sex video on a steampunk computer (like the one below, courtesy ofBoing Boing) be somehow more erotic than downloading it on a regular laptop? Would it miraculously become “naughty” instead of soul-killing?

Do we envy the Victorians for the very concept of “naughtiness”?

“What we all dread most,” said G. K. Chesterton’s detective priest Father Brown, “is a maze with no centre.”

The mood of existential dread that gripped the American psyche in the wake

of WWII was largely unconscious, and so it expressed itself in

irrational ways — in the hysteria of the Communist witch hunts, for

example, and in the mythology of the film noir,

which characteristically sent an impotent man into the heart of a

nightmarish moral labyrinth from which there was no escape.

There was a variant on the classic noir paradigm which sent a cop or a government agent into that same dark underworld, but he was armed with the positive values of the official

culture and backed by its official institutions — he not only escaped from the labyrinth, he straightened it out, brought it into the light and broke its evil spell.

The first film of this kind, and a model for all the rest, was The House On 92nd Street

from 1945, an F. B. I. procedural about the uncovering of a Nazi spy

ring operating inside the U. S. during WWII. It had a

quasi-documentry approach and was obviously designed to reassure

Americans that their government had the issue of existential dread well

in hand. It’s a taut, entertaining thriller, with fascinating

location photography, but its celebration of the F. B. I.’s

omnipotence and infallibility couldn’t, even at the time, have been a

profound assurance to people who felt that something had gone terribly

awry with the world — something that the Allied victory in the war

hadn’t really set right.

This feeling was addressed but not answered in genuine film noir,

which is what gave the form its power — turned its image of the urban

labyrinth into an enduring variation on an ancient myth.

Interestingly, the terrifying image of the maze with no center, and no

exit once entered, can also be found I believe in the best films of

Frank Tashlin — all comedies.

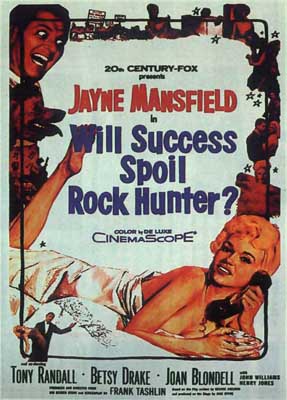

In The Girl Can’t Help It and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?,

Tashlin offers a satire of post-war American culture which also has no

center and no exit point. These movies mock modern media from within the

modern medium of film, which is itself mocked, deconstructed, leaving us

with no reliable perspective from which to judge any of their judgments.

They savage the modern rat race but also savage anyone who tries to

escape it. In Tashlin’s vision, as in film noir, American culture is a maze which can’t be navigated, in which every passage circles back on itself.

In Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?,

for example, Tashlin attacks modern advertising and product placement

on television, then proceeds to plug his own earlier film The Girl Can’t Help It

within the new one. Tashlin’s films are funny but deeply

disturbing. Their vision of America is profound and just as noir as the dark streets of the great films noirs. The fact that Tashlin’s darkness is rendered in garish, overheated

Color by Deluxe is just one more of the radically disorienting ironies

of his method.

[For more on The Girl Can’t Help It, go here. The image of the labyrinth in film noir is discussed helpfully in Nicholas Christopher’s book Somewhere In the Night.]

This

is Alan Fraser, an old friend from the newsgroup rec.music.dylan, which

I was once heavily involved in but have long abandoned (it got too

creepy.)

It was Alan who answered the first question I ever posted

there, around 1998, seeking track information for an import Dylan

collection called Masterpieces. Alan is the world's foremost

authority on Dylan rarities — officially released but rare or obscure

recordings. Here's a link to his invaluable web site database:

Alan

is also a fan of sci-fi and has passed along a lot of great book

recommendations in that genre. I never knew what Alan looked like until he sent this picture — he

lives in England — but I imagined his jovial smile almost exactly . .

. it's just there in what he writes, in his cheerful helpfulness. He was

the guy on the newsgroup who always answered the question of a first-time

poster with good-natured seriousness, even if it was a question that had

been asked a million times before.

Storytelling has been degraded in our time by

corporate entertainment, which wants a mathematical formula for stories

that even a studio functionary can understand. Hence the

“character arc”, which reduces a human being's story to a geometrical

figure, and the “hero's journey”, which reduces it to a grocery list of

plot points.

The heart of any real story, however, is mystery.

Achilles

has no character arc — neither do Alice of Wonderland or

Hamlet of Denmark. What they have in place of a character arc is

the illusion of an irreducible, inexhaustible inner life — in short, a

character.

Here's a wonderful quote from Stephen

Greenblatt's recent biography of Shakespeare, Will In the World:

“Shakespeare found that he could immeasurably deepen the effect of his

plays, that he could provoke in the audience and in himself a

peculiarly passionate intensity of response, if he took out a key

explanatory element, thereby occluding the rationale, motivation or

ethical principle that accounted for the action that was to unfold.

The principle was not the making of a riddle to be solved, but the

creation of a strategic opacity. This opacity, Shakespeare found,

released an enormous energy that had been at least partially blocked or

contained by familiar, reassuring explanations.”

This sums up what's

wrong with Hollywood filmmaking today. Anything you tell the audience

to feel they don't have to feel, because they know you'll feel it for

them. In a Hollywood film today, for example, it's extremely reassuring to be introduced to a little girl with

no legs whose lifelong dream it is to climb Mount Everest, because you

know that at the end of the film she will, by the use of artificial

limbs or even by dragging herself along with only her arms, get to the

summit. The only issue is how it will happen. It becomes a puzzle

rather than a story.

But in trying to figure out why Hamlet is behaving the way he's

behaving, and never being given a coherent explanation, you

mysteriously internalize his experience.

Once a character has a legible “arc” she is no longer a character — she's an arc . . . a shape, not a person.

Understanding this is like possessing the storytelling

equivalent of the secret of nuclear fission — it's the key to a

radical new phase in popular entertainment, which I expect will unfold

in the next two to three years as the Internet gradually erodes the

corporate grip on distribution.

It will at any rate at least be possible to tell real stories again —

stories that engage the inner experience of an audience. It will seem

incredibly new and exciting — though it's as old as Homer, as old as

the oldest storyteller Homer learned his stuff from. But that's the

thing about stories — the great ones always seem brand new, even when

you know exactly how they'll come out . . . because they're like

emotional chain reactions that happen inside you, not like lines on a

geometrical chart. It's the difference between E=mc² written on a

piece of paper and what happened

on the test site at Los Alamos.

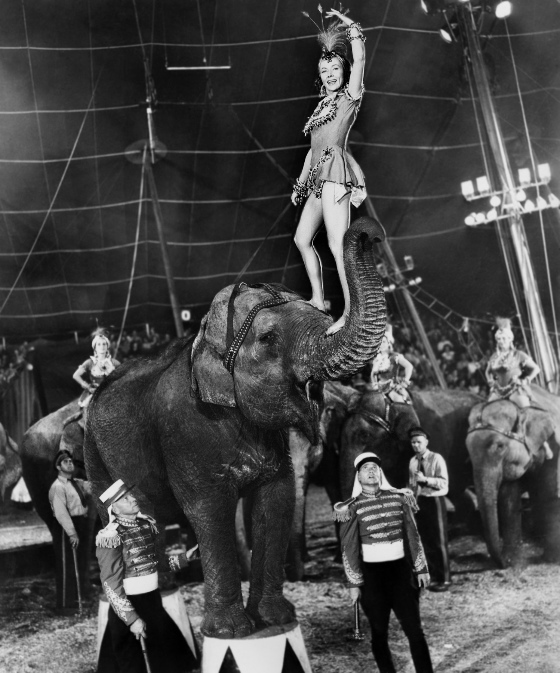

. . . to think about Gloria Grahame.

Sometimes it's nice to think about Gloria Grahame standing on top of an elephant.

Kierkegaard once remarked that many of the greatest human virtues, like loyalty and faithfulness over time, are almost impossible to dramatize, which is why there are legions of great dramas about adultery but hardly any about good marriages.

A drama about a good marriage has to deal with subtleties, with crises that don’t lead to disaster, with everyday acts of love that don’t erupt into shattering passion.

And yet . . . is there anything more suspenseful than a good marriage? Is there any murder mystery more intricate than the process of accomodation, of creative sympathy and adjustment which keeps a good marriage alive?

Fred Zinneman’s The Sundowners, from 1960, is a movie about a good marriage — about the accumulation of small dramas, never quite reaching a climax, never quite being resolved, that hide within the miracle of a good marriage.

Set in Australia in the 1920s, it’s about a family of itinerant sheep drovers. It’s filled with spectacular location photography and has a few suspenseful action sequences, but at its

heart are a hundred and one things that don’t go wrong, when they should. The father and mother of a teenage son who make up the family don’t change in the course of the film — they have no “arc”, to use a bit of terminology from modern Hollywood storytelling, which turns

characters into geometrical shapes. We just watch scene after scene in which they struggle to remain who they are — two married people deeply in love with each other, deeply committed to each other.

We watch the compromises they make, their acts of forgiveness, their miraculous triumphs of sympathy and empathy, their well-worn joy in each other.

Then suddenly . . . nothing happens. They endure.

As the couple, Robert Mitchum and Deborah Kerr give miraculous performances, quiet and understated — you need to watch them carefully to see the deep currents flowing between them . . . but they’re there, especially in their bedroom talk, where you get glimpses of a grown-up sexuality that mainstream filmmakers rarely portray, probably because they’ve never gotten closer to it than passing a copy of Anna Karenin on their way through a Barnes and Noble bookstore.

The Sundowners may not be great drama, but it’s spiritually exhilarating — something more than drama, perhaps.

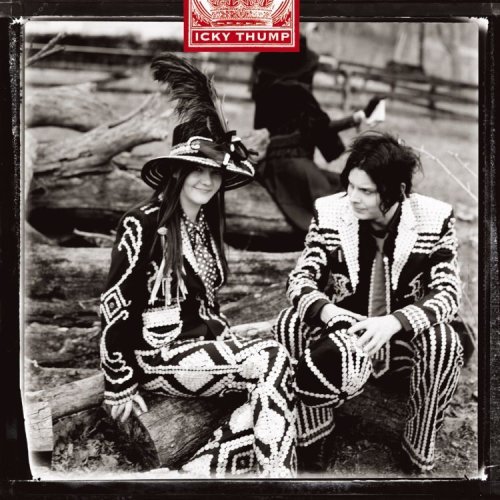

Mark your calendars — the new White Stripes album Icky Thump arrives on 19 June. Meanwhile, here's a video

of the title song to whet your appetite. It seems to have been

partly filmed in a Mexican whorehouse, and the lyrics have a message

for people obsessed with illegal aliens from south of the border —

“kick yourself out . . . you're an immigrant, too.”

¡Viva Stripes!

You could get lost in the spatial complications of this painting, Destiny

by John William Waterhouse, which take a while to sort out. The

sorting out is part of the artist’s strategy for drawing you into the

image — as the female figure’s dream of the adventures those ships

could take her on becomes your own. For her the ships are reflections

in a glass, for you they’re paint on canvas — dreaming makes them both

real.

Someone once remarked that there's no such thing as a bad film noir. It's a strange propostion and the strangest thing about it is that it's pretty much true.

I've just watched over 30 films noirs

and none of them was anything less than a wondrously entertaining

B-picture. There are some clunkers that are labelled films noirs but really aren't — like Otto Preminger's Whirlpool,

for example, which is in fact a Hitchcockian suspense thriller made by

a man who had no clue as to how Hitchcock created suspense . . . but even among the faux noirs, films that are noirish only in visual style, for example, most have dialogue and images that are thrilling.

I'm not sure how to explain this consistency of quality except by suggesting that noir

represented such a release from the thematic and stylistic conventions

of the traditional studio product that filmmakers responded with an

outburst of pent-up creativity and daring. They must have known

that they were inventing a new kind of film, even if it didn't have a

name yet, and the fact that there were no set rules for this kind of

film made it hard for the studios to wrestle it into a set

formula. Films noirs

were relatively cheap to make, and people couldn't seem to get enough

of them, so the studios stepped back and let the experimentation

continue — for almost 20 years.

The first film that displayed the characteristic visual style of the noir was a fairly routine murder mystery called I Wake Up Screaming (above) from 1941. Double Indemnity, from 1944, gave us protagonists who were morally currupt to the core. Neither was, to my way of thinking, a genuine film noir, but Double Indemnity

was a radical indication that a change was on its way — that audiences

could accept a darker view of the world than the Hollywood studios had ever been

willing to embrace.

As early as 1945, in Edgar G. Ulmer's no-budget thriller Detour,

the combination of an exaggerated, expressionistic visual style and a

sense of the world as morally unhinged at its core produced a template

for the classic film noir, a vehicle for the subterranean mood of existential dread that gripped America in the wake of WWII.

None of the movies made about the war itself ever expressed as

eloquently its psychic cost to a generation of Americans as did the

movies we now call film noirs.

They crackle with the excitement of artists suddenly allowed to deal

with truths that couldn't be addressed in the official view of

things. Corporate entertainment tends to gravitate towards the

official view of things but there are times when the official view of

things diverges so radically from the actual mood of the audience that

accommmodations have to be made. Film noir was one of the most radical of those accommodations.

Here’s a guy you definitely wouldn’t want to invite into your

home. He doesn’t seem to understand the purpose of an ashtray.