Another report by Paul Zahl from his recent trip to the area around Paducah, Kentucky:

This is one of the main avenues of the ancient Oak Grove Cemetery in

Paducah. Here Irvin S. Cobb is buried, here is where John Ford came in

1961, while shooting his section of How the West Was Won nearby, to pay his respects to his old friend, and here is where the prototype for Cobb's (and Ford's) “Judge

Priest” (i.e. Judge William S. Bishop) is buried, right beside Silent Avenue.

This is Cobb's grave in Oak Grove Cemetery:

The inscription

reads, “Back Home”. A dogwood tree, as per his dying request, shades the

grave. He wanted only the Twenty-Third Psalm read at the grave,

together with the choir of a local African-American congregation to

sing “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “Deep River”. Cobb's wishes were

honored.

Mercy Avenue is another of the main axes of Oak Grove Cemetery. I

got up high on some crumbling steps leading into a mausoleum in order

to get this one. I think if we could all spend some time on “Silent

Avenue” and then perhaps forever on “Mercy Avenue”, we would be in

excellent shape.

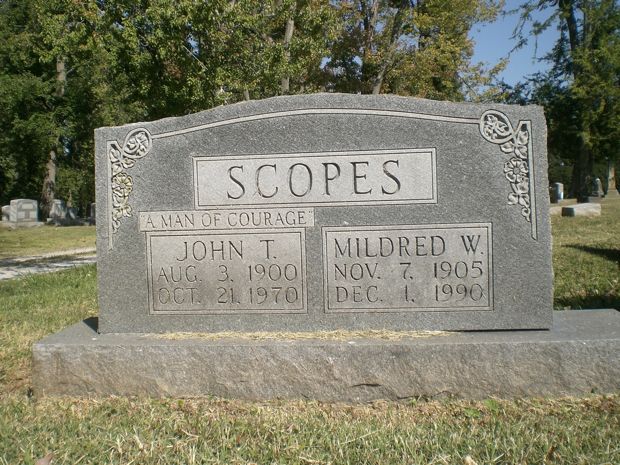

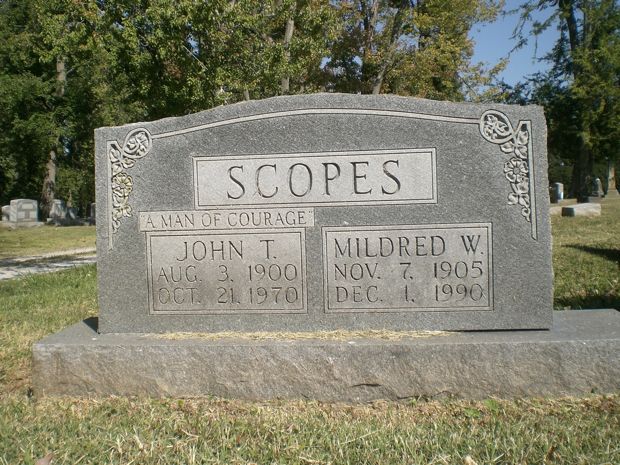

Just a few “blocks” down Silent Ave from Cobb's grave is this one — the grave of John Scopes, the

teacher of evolution in the Tennessee public schools who was prosecuted

in the famous “Monkey Trial” of 1925:

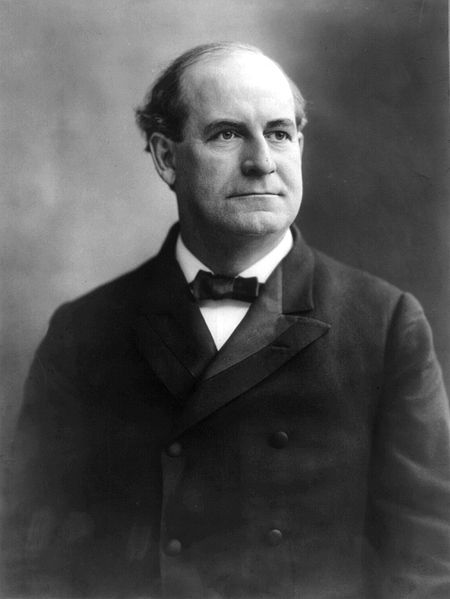

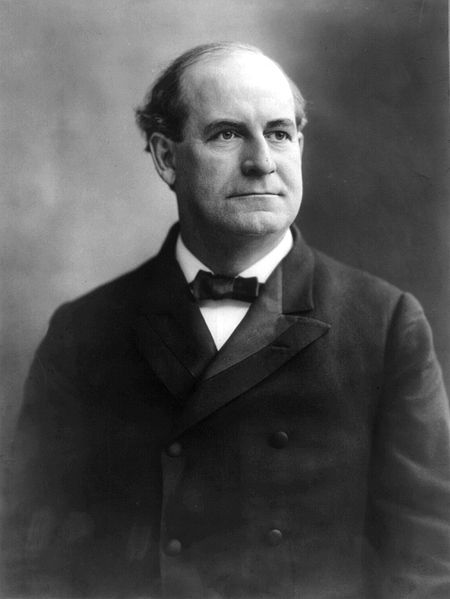

This is the man whom Clarence Darrow (or

Spencer Tracy, for those of you who remember the movie about the trial, Inherit the Wind) defended, and who won, after a fashion. He was found formally guilty and

fined $100, but the judgment was regarded by everyone at the time as a

victory for free speech, and even evolution itself. In the film, Frederick March played William Jennings

Bryan (below), who stumbled in attacking this man, and never fully recovered from

the moral defeat which the trial was for him.

What a picture of

Twentieth Century America, in one acre of ground — Cobb, now no longer

famous, with a big grave near the entrance; his prototype for “Judge

Priest” buried nearby, on Mercy Avenue, a man who kept on getting elected

because the Confederate veterans of the county were “Yellow Dog”

Democrats — that is, people who would vote for a yellow dog before they would vote for Republican; and then, after all that, down the way, the simple memorial

to John Scopes, “A Man of Courage”.