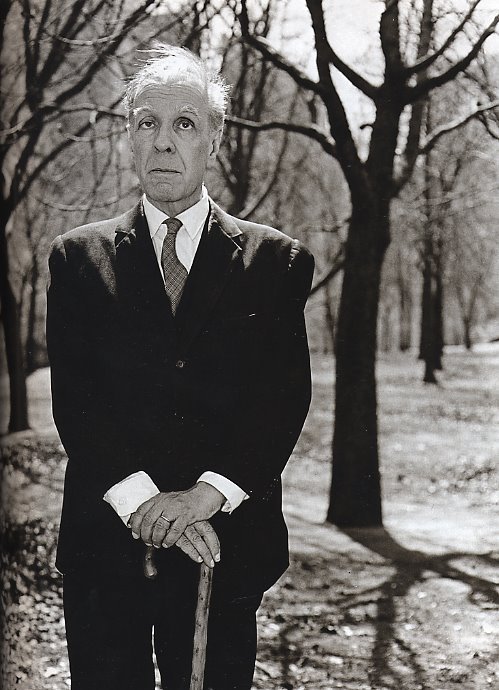

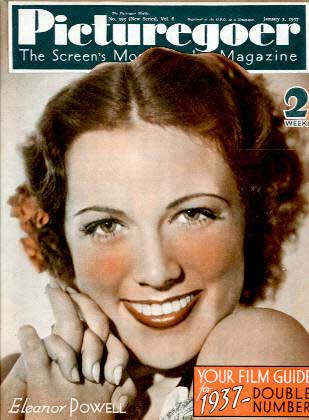

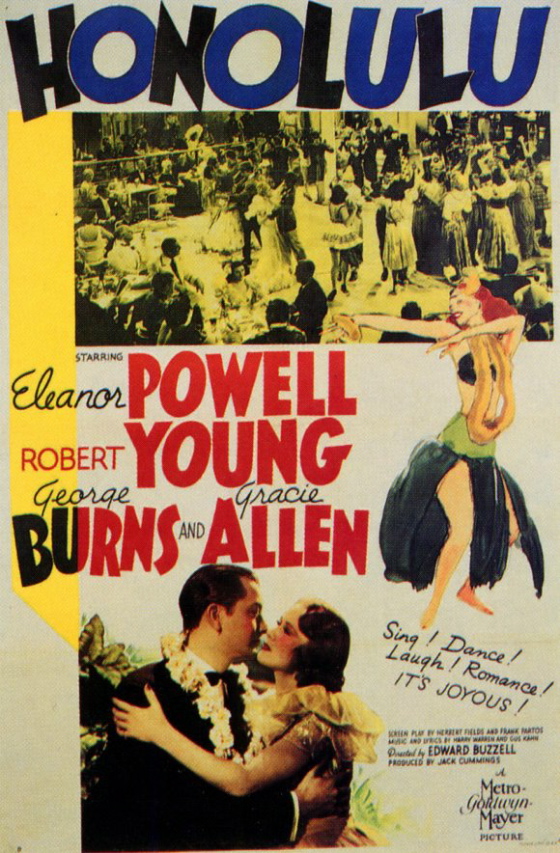

Jack Cummings was MGM's third-string producer of musicals from the late Thirties to the mid Fifties (after Arthur Freed and Joe Pasternak.) He was unimaginative but reliable, able to churn out respectable product with occasional passages of sublime magic. One such bit of product from 1939 was Honolulu, an Eleanor Powell vehicle.

The film has an amiable but uninspired sit-com plot, centering on a Hawaiian pineapple grower and a big movie star who look exactly alike and decide, for various preposterous reasons, to switch places for a few weeks. Robert Young plays the dual role. As the movie star seeking a respite from hysterical fans he falls in love with Powell, a dancer with a gig at a Honolulu night spot.

In the dialogue scenes, Powell is every bit as bland and pleasant as Young — they're acceptable company for a bit of romantic comedy fluff. So far so good. When the Hawaiian drums start to throb, however, and Powell starts dancing, she sizzles with an intense sexuality that leaves Young wailing on the margin of non-entity, both dramatically and as a cinematic presence. After Powell's first big number, the film no longer makes any sense as a love story.

Powell's three big numbers in the film, all solos, two with a corps of other dancers behind her, are stunning, though — they make the film worth watching, and revisiting. In the first, she partners with a jump-rope, and makes it look sexier than Young. In the last she does a fierce hula in a grass skirt, first barefoot then in tap shoes. It has to be seen to be believed — her hip movements are simply indecent.

Another of the film's delights is Gracie Allen, who plays Powell's partner in her nightclub act. She flits in and out of the plot delivering some first-rate vaudeville gags with her usual brilliance. If you think of Honolulu as a program of vaudeville turns, rather than as a book musical, it's much easier to enjoy. Powell, like Allen, was a product of the variety stage, so it's really not that much of a leap. (George Burns is also in the film, but has no scenes with Allen, and flounders a bit with the less-than-amusing material he has to work with here.)

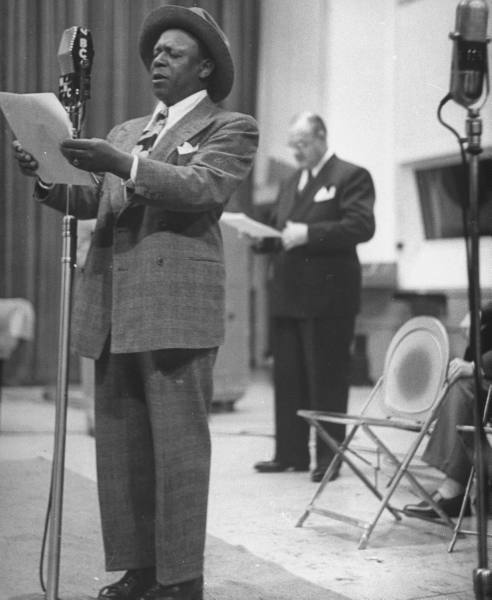

The film has some problematic racial stereotypes. Eddie Anderson is made to do a gibbering “I'se just seen a ghost!” turn, which is doubly offensive because it clashes so markedly with Anderson's wry and skeptical comic persona, which Jack Benny exploited so well in his radio and TV shows. Using Anderson as he's used in Honolulu is just an example of the mindless demeaning of blacks. Willie Fung does a more amusing stock Chinaman turn, in which he gets to engage in a bit of one-upsmanship over his patronizing boss.

Then there's Powell's blackface number, in which she dances an imitation of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. This cannot be simply dismissed, however disturbing the very idea of blackface has become. There is no trace of condescension in Powell's tribute to Robinson — it's more an act of admiration, even envy. Powell took lessons from the great black tapper and she imitates him convincingly — though her version of his tapping up and down stairs is just a faint echo of Robinson's signature routine. She would probably have enjoyed dancing a romantic tapping pas de deux with Robinson — he's one of the few dancers who could have held his own with her, and then some — but that would have been inconceivable in 1939, probably even in 1969 in any mainstream showcase.

So Powell became Robinson for a few minutes. It's hard to see the impersonation as anything but an act of tenderness and love.

The film was directed by journeyman Edward Buzzell. Bobby Connelly did the simple but effective choreography — he did the simple but effective choreography for The Wizard Of Oz that same year. Sadly, Honolulu is not yet available on DVD, though it's shown from time to time on TCM.