The first part of a remarkable two-part essay by Paul Zahl on the James Gould Cozzens novel By Love Possessed and its screen adaptation by John Sturges.

A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET (Part One):

The once extremely popular novel of the year 1957 entitled By Love

Possessed, written by James Gould Cozzens, was made into a Hollywood

movie in 1960 and released the following year. The novel tells the

story of Arthur Winner, Jr., a very sane and prudent attorney living in

a small town in mid-Atlantic America, as his life unravels over a

period of 49 hours. Arthur Winner, who is always referred to in the

novel as “Arthur Winner”, navigates defending a pretty indefensible

young man, for whom Arthur Winner feels personally responsible, from a

charge of rape; as well as helping a legion of citizens of Brocton,

their small town, with their unending personal, legal, and financial

problems. Somewhat priggish — that is what the many hostile critics

of By Love Possessed called Arthur Winner — but also unflappably calm,

Arthur Winner succeeds in holding the wolf of anxiety at the door,

until . . .

Because I hope this post may succeed in making you want to read the

book, I won't give away what becomes of the limits of Arthur Winner's

ability to keep it together.

I will say that the brilliant and wise hero is, credibly, reduced to a

humbled condition, almost a desperate condition. And, partly through

the aid of his friend and law partner Julius Penrose, Arthur Winner

finds the hidden door, the still small voice of an answer, through the

box canyon of his shattering humiliations and disappointments. The

novel's resolution is noble, lyrical, and possibly true . . . to life.

Because By Love Possessed was a number one best-seller for many months

— something close to a national sensation in the fall of 1957 —

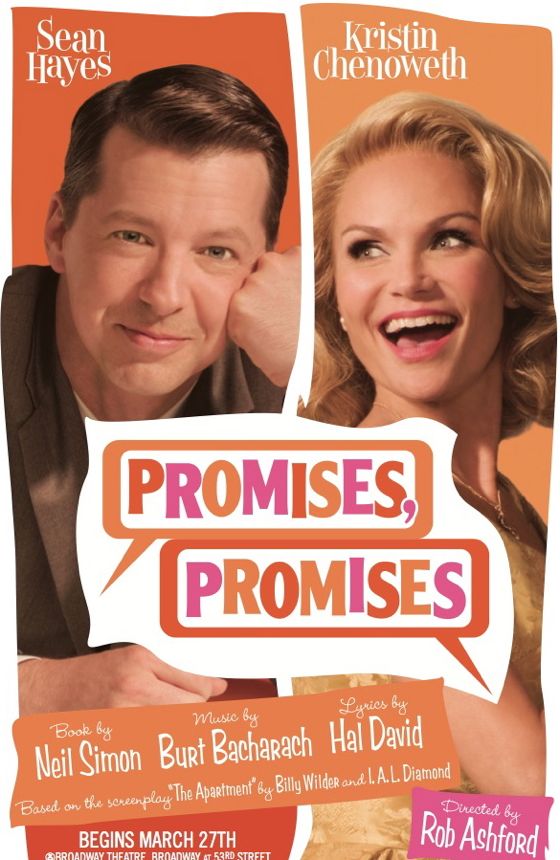

it was filmed as an “A” production in 1960 by an independent production company releasing through United Artists. The movie version starred Efrem Zimbalist, Jr. as

Arthur Winner, Jason Robards, Jr. as Julius Penrose, and Lana Turner as

Marjorie Penrose, the extra-marital love interest of the Man of

Reason, Arthur Winner. Other familiar actors played supporting roles,

such as George Hamilton, Thomas Mitchell, Susan Kohner, and Barbara Bel

Geddes. By Love Possessed was directed by John Sturges, who also

directed The Magnificent Seven, released in 1960. John Dennis wrote

the screenplay, which was a big challenge, as the novel is actually an

epic, with many interlocking characters and a lot of talk and a lot of

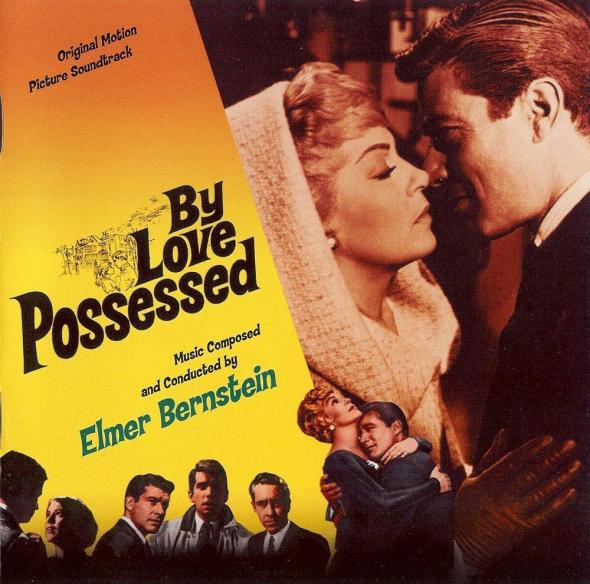

ideas. The music, which is wonderful in a kind of 1950s soap-opera

manner, was composed by Elmer Bernstein.

I want to say something about movies and books in relation to a comparison of the two versions we have of By Love Possessed.

But first, two additional facts about it:

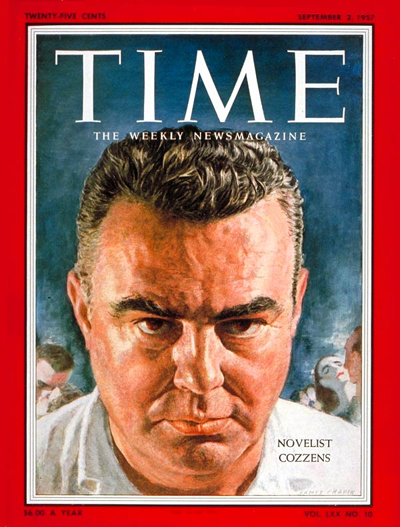

This novel became the object of a famous attack in print by Dwight

MacDonald, in the January 1958 issue of Commentary magazine. Because

Cozzens refused to take the trouble to check the copy for a Time magazine cover story about him and By Love Possessed, several extremely

damaging statements, which he claimed later were not his words at all

but the words of the two hostile writers who interviewed him, had

appeared in print, for the country to see. They made Cozzens sound

like a social snob, who was also bigoted toward African-Americans and

Jews. Although he was a snob — more a “meritocracy”-type snob than a

WASP snob — he was not a racist. His 1949 Pulitzer-Prize winning

novel Guard of Honor had exposed racial segregation in the Air Force,

taking the lid off a subject that many people did not like to talk

about then. Cozzens was also not anti-Semitic. His only real friend,

for he was a hermit in effect, a little like J. D. Salinger in that way,

was his wife. And his wife was Jewish, a well known literary agent in

Manhattan and a liberal Democrat. Nevertheless, certain attitudes of

some of the characters in By Love Possessed are intolerant. So Dwight

MacDonald, stoning the book and its reclusive author, believed he was

taking on “Eisenhower-era” intolerance and complacency.

James Gould Cozzens' career never recovered from MacDonald's attack,

which was widely accepted as being true and accurate. The January 1958

attack on Cozzens was his Nightmare on Elm Street. He had written

incisively and even shatteringly, I believe, about “Ivy League”

characters in a small mid-Atlantic town, a town full of Water Streets,

and Market Streets, and Elm Streets; and then paid a nightmarish price

for it. You can read about the personal effects and “after birth” of

the abuse he took from the critics, in the journals he kept from 1960

to 1964 when he was living in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

Oh, and Cozzens was also accused of being anti-Catholic. And

anti-Catholic he was, no doubt about it. Religiously, the writer saw

himself as a “P. E. agnostic” (i.e., Protestant Episcopal agnostic), who

regarded most expressions of Christianity as superstitious.

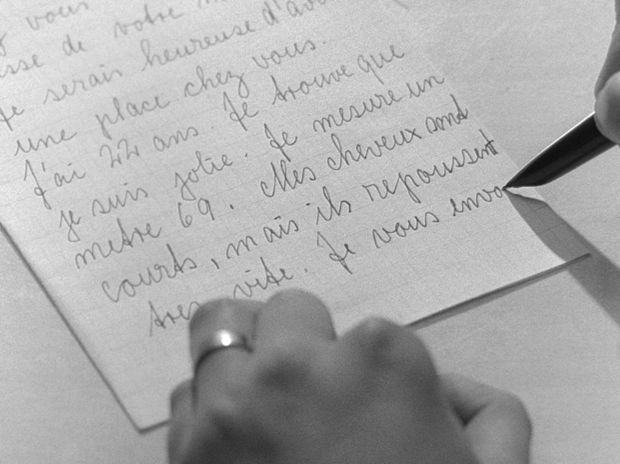

The second fact I need to mention about the book in relation to the

movie is that the author saw the Hollywood version twice and wrote down

his reactions. This is how James Gould Cozzens reported his first

viewing of By Love Possessed in his journals [VII 19-VII 22 (1961)]:

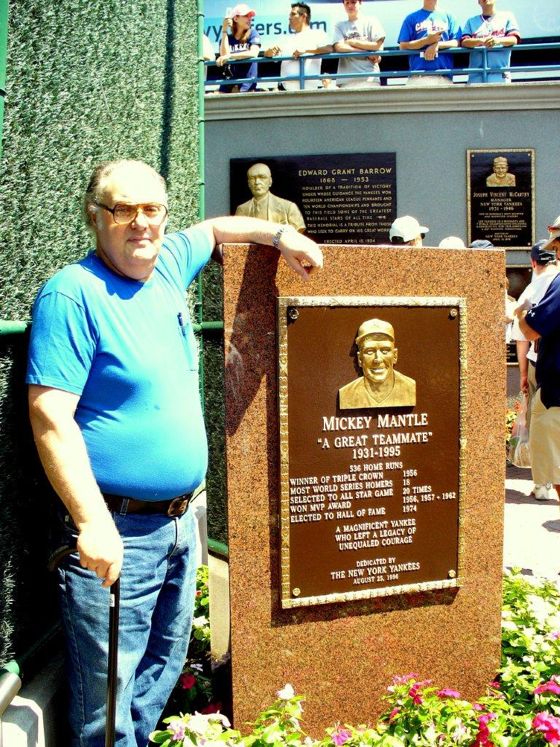

By Love Possessed was opening at the Capitol [i.e., in New York City]:

and though I thought little of the idea, at loose ends after lunch at

the Harvard Club [above] I followed S.'s [i.e., his wife's] suggestion and went

up. I must admit I got several surprises. For one thing, the

photography was simply and even, sometimes, amazingly, beautiful. For

another, the direction gave constant signs of intelligence, especially

in small touches, often faithfully taken from the book. When law, for

instance, was touched on, the to-be-expected nonsense was carefully not

made of it. The simplification, by sometimes telescoping, sometimes

eliminating characters obviously necessary if the material was to be

got into any actable form, showed evident judgment. Flabbergasted, I

can only say that, taken all in all, I found it a good deal better than

the critics (who probably missed all the good careful small points)

claiming it made a mess of the book, had allowed.

Later, on April 21st, 1962, Cozzens saw the movie again, this time with his wife. Then it was showing in Williamstown:

S. hadn't seen the By Love Possessed film and when it turned up

(second time around) at the Spring St. theatre today insisted on

going. Seeing it a second time, I was again impressed by much really

beautiful photography, and a number of excellences of small detail and

minor casting — the man, whoever he was, cast as “Dr. Shaw” [i.e.,

Everett Sloane] in the trifling part allowed him was almost

disconcerting, he was so exactly in face and manner what I was seeing

as I wrote.

But it was as plain as ever that the job they undertook was impossible:

the book defeated them at every turn and was indeed specifically

intended to. [PZ's Italics.]

A play, an acted entertainment by definition, can't be “honest”

exhibiting True Experience. Actors act “parts”: plays must provide “parts”. The whole basis is “Let's Pretend”. Anything “real” or “true” will destroy or at any rate vitiate this basis. Life is life,

not a play: a play is a play, not life. It seems to follow that an

effective play must cut loose from considerations of: is this probable?

(or even: is this possible?) and proceed on the principle of, say,

Hamlet. Never mind whether this situation makes sense, never mind if

it's obviously impossible. Assume it to be the situation: Now, what

next?

I think this has to be interesting to people who are interested in

movies. Here is a deep and dense novel — even the people who hated it

admired its craft and structure, and its verisimilitude to life as

lived by people like that — which was translated into a lavish

Hollywood production with a famous star and the most costly energies of

studio film-making. And the novel's author, who rarely went to movies

and rarely talked to people or even saw them on the street, approved

of the full treatment.

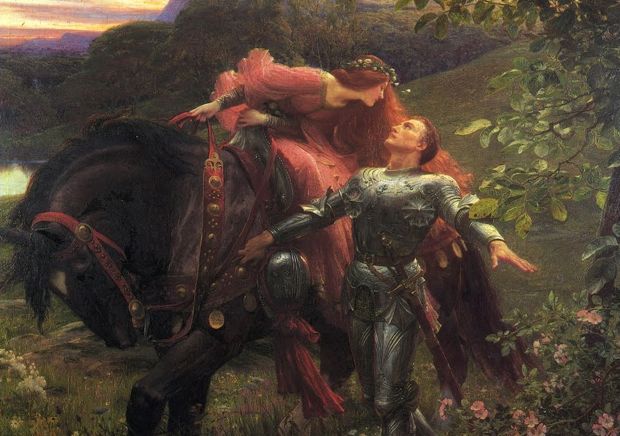

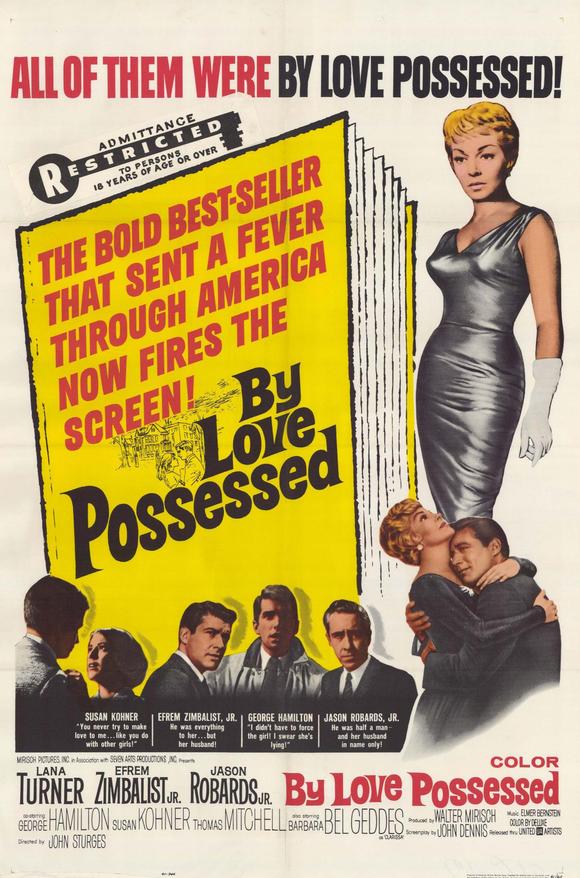

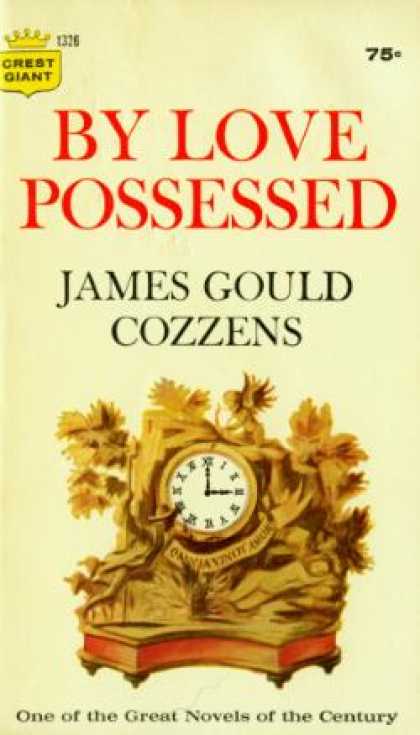

Now, with the book in one hand — my wife's family owned a

first-edition with its famous cover of the “Omnia vincit amor” clock [the paperback edition, with the same cover design, is pictured above] —

and a videotape of the movie in the other (“Miss Turner is as fine as a

red hot flame!”), I would like to compare the two, looking for

similarities and disparities. Since I love the book, admiring

absolutely its reportorial and philosophical ambition, I feel a little

vulnerable. But here goes . . .

Click on the link below for the second part of this essay: