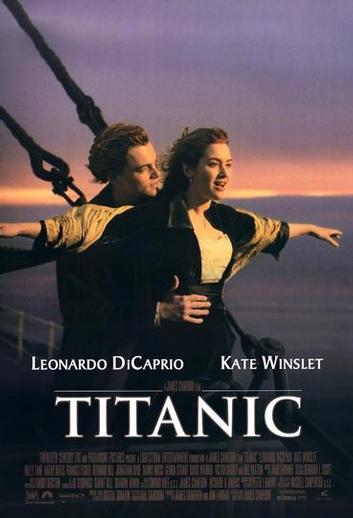

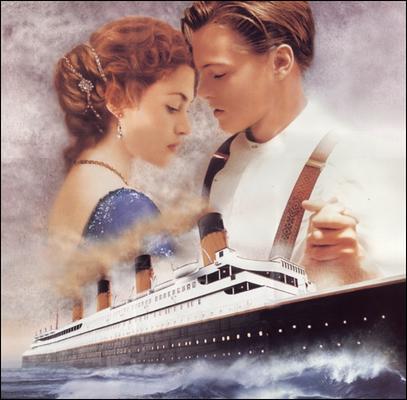

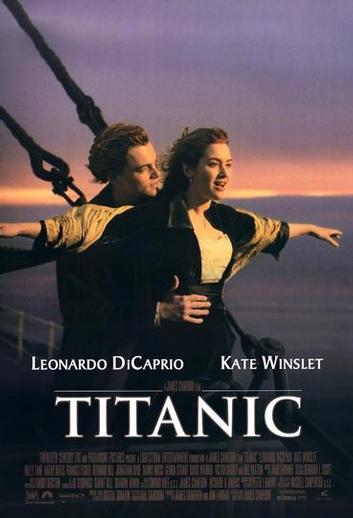

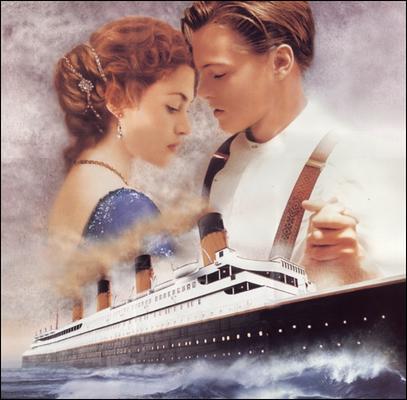

For intellectuals, the best way to appreciate James Cameron’s Titanic might be to imagine it as a silent film. In other words, start with its images and work backwards towards its literary structure, seeing how the latter serves the former, instead of the other way around.

Instead of criticizing Cameron’s screenplay for its clunky dialogue and melodramatic excess, try to think more clearly about what a screenplay is, or ought to be — a framework around which images can coalesce to tell a story quite beyond the range of words on a page. It would be silly to try and appreciate Don Giovanni by analyzing Lorenzo da Ponte’s libretto for the opera as a work of literary art. Better to start with what it served — the music of Mozart, and what that music achieved . . . a sublime evocation of transient sexual love, and one of the supreme masterpieces of lyrical theater.

All of Cameron’s primary effects reside in his images. The real climax of his story lies in old Rose’s eyes — the gaiety and adventure and peace they convey, Jack’s gift, earned by her faithfulness to him and to her promise. Cameron uses digital effects as eloquently as camera tricks have ever been used in a film to link old Rose to the period tale we think we’re watching — morphing from the young Rose’s eye to the old Rose’s eye, from Jack and Rose “flying” on the bow during the ship’s voyage to their ghosts lingering on the encrusted wreck at the bottom of the ocean.

Cameron has a gift for orchestrating movement on screen to create an almost hallucinatory sense of space within the individual frame, and an ability to preconceive digitally composited shots as though he were photographing the real thing from a seemingly inevitable perspective.

The vehicle for Cameron’s imagery in Titanic is, as it was so often in the silent era, unapologetic melodrama, a simple structure pitting irreconcilable forces against each other and creating suspense about the outcome of the collision — and less about the nature of the outcome than about its how and when. That is the source of the film’s narrative momentum, and of that alone — no one has ever experienced the plot of a melodrama as anything more than a ride. It’s the inflections of the tale delivered in the images that give the film its depth — that make us experience the crude conflict as interior emotion . . . just as we do with the crude conflicts summoned up in dreams to express complex psychic states.

Melodrama remains a potent artistic strategy, but it’s one lost on a modernist who has been trained to reject as “phony” anything that smacks too closely of the Victorian. Fourteen year-old girls, who don’t know what 19th-Century melodrama is, and thus don’t know that it is intellectually discredited, experience its power and expressiveness as forcefully as intellectuals of the Fifties experienced Brecht.

The good news for all intellectuals is that, with a little thought and study — and perhaps a little humility in the face of what you don’t know about the history of film, about melodrama, about antique but still wholly viable dramatic forms — it is possible to enjoy Titanic with your brain as well as your heart.

As artists of the Renaissance discovered, a backward glance at forgotten masters — like Griffith and Vidor, in this case — can sometimes revivify an art, and take it more surely into the future than an avant garde that has lost its way.