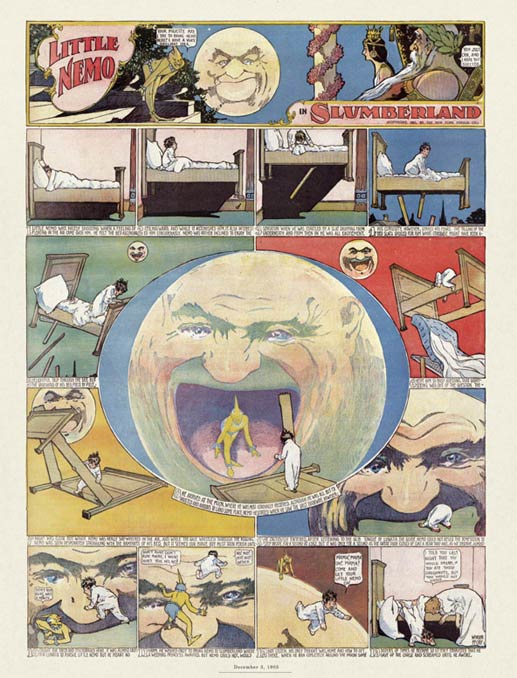

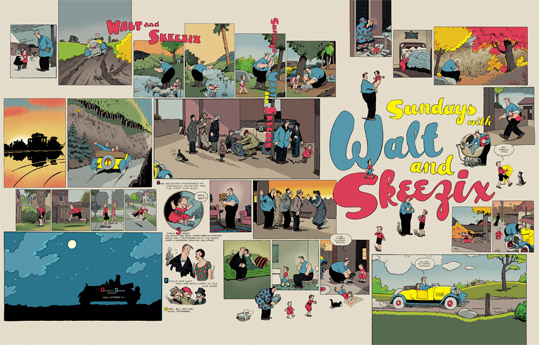

The second of the four coolest books published in the past few years is another oversized volume from Sunday Press Book — Sundays With Walt and Skeezix. It collects a number of Sunday pages from Frank King’s brilliant long-running strip Gasoline Alley,

one of the glories of American popular art. I’ve written before about the

series from Drawn and Quarterly Press which is reprinting the entire

run of the daily strip in a succession of handsome volumes — but the Sunday

pages are something else again.

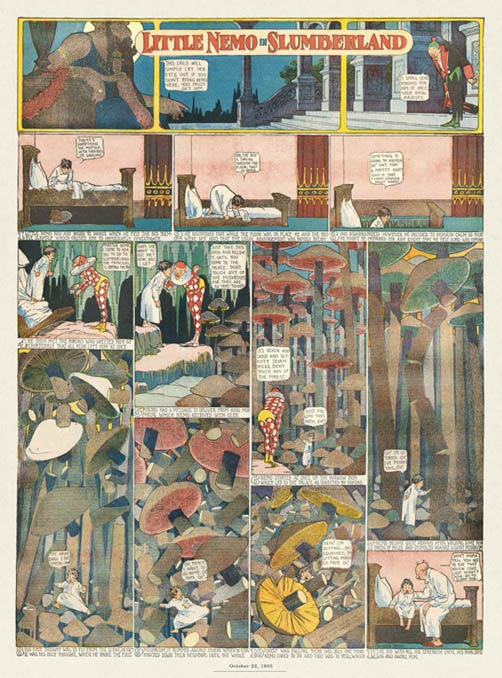

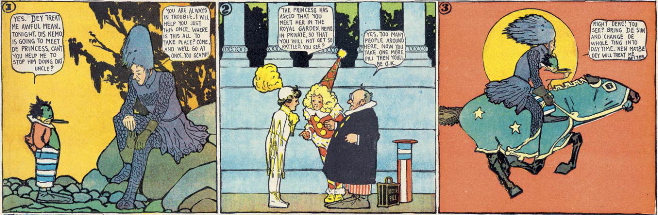

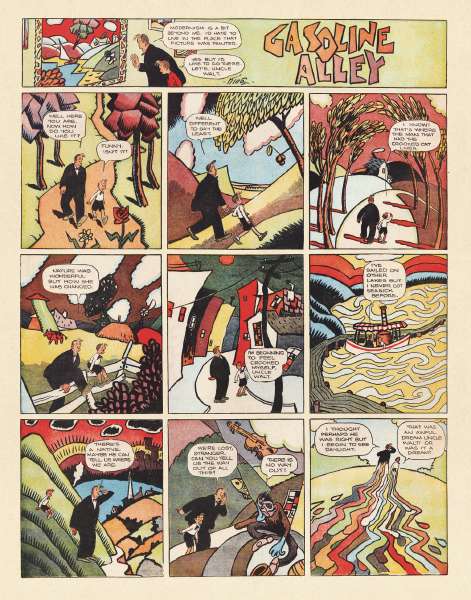

In the daily strip, King created a narrative masterpiece graced with

many flights of visual invention, but in the color Sunday pages his

visual imagination grew much bolder — lyrical, almost abstract at

times. He looked at the Sunday page sometimes as an arena for the

wildest experimentation — to see just how far the expressive potential

of a comic strip might reach.

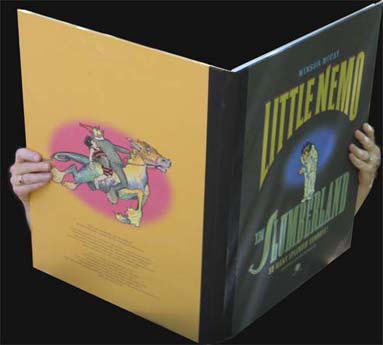

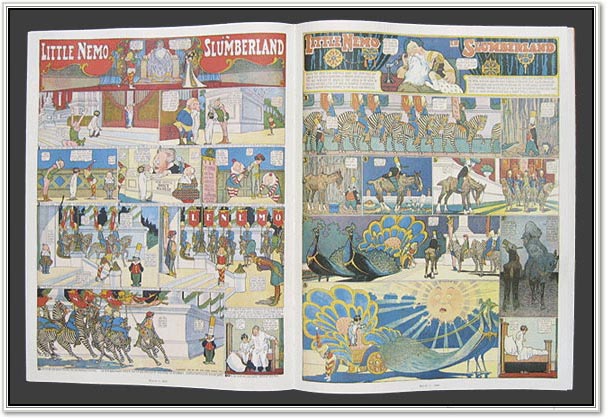

In the Sunday Press collection we can see these Sunday strips almost as

their first viewers did — in the same colors and in the same size.

It’s a measure of our culture’s descent into mediocrity and triviality

that no work of such ambition and grace now accompanies any daily

newspaper in the land, and certainly no cable news channel. It

used to be assumed that the visions of great popular artists ought to

be part of every American’s daily dose of media. Today only cheap

digital graphics and portentous musical jingles accompany the canned “news”

doled out by the major media outlets.

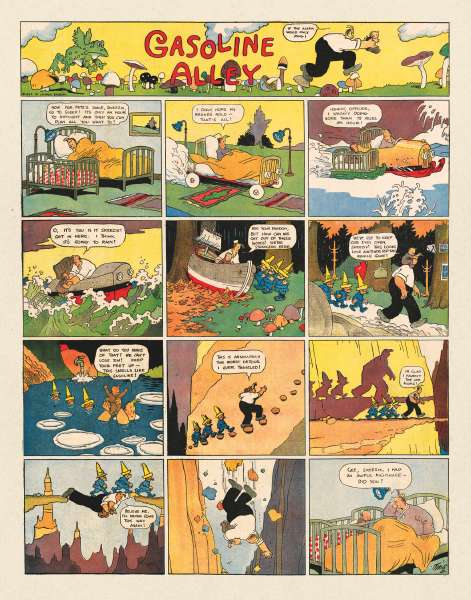

Americans have never liked being spoon fed “culture” — meaning culture

that somebody decided was good for them. That was the beauty of

the comic strip — it was an art form so unpretentious, so vernacular

and casual, that Americans could consume it over breakfast or before

dinner without a trace of self-consciousness or social anxiety. But its

expressive range was almost limitless. We know that from the work

of artists like Frank King, who in their own quiet but audacious ways

tested its limits to the full.

You could read through these comics and weep that stuff this great used

to be thrown up on the porches of millions of Americans by

paperboys every Sunday morning — and isn’t anymore. Or you could read through them

and take heart at the fact that stuff this great could ever have been part of

American popular culture — and so might be again. Why not?

You can buy Sundays With Walt and Skeezix here.