One objection commonly made to Victorian academic art is that it’s too “photographic” — that it tried for a kind of photorealism which the camera had made redundant.

I think this objection is misguided on two counts. The first is that

the “photorealism” of the Victorian academics far exceeded the capacities

of the 19th-Century camera. The academic painter could achieve color

effects which film stocks wouldn’t be able to record until late in the 20th

Century. The Victorian academics could also capture motion in ways the

still camera could not until the early 20th-Century, with the advent of

faster film stocks and shutter speeds. The Victorian realist painter

was in fact developing his aesthetic in precisely those areas where the

cameras of the time were deficient.

More importantly, photorealism is not an aesthetic fault. Painters

since the Renaissance have often striven for hyper-realistic effects,

and have sometimes used proto-photographic technologies, like the camera obscura, to that end. The fact that Van Eyck and Vermeer might possibly have used the camera obscura as an aid in draftsmanship is surely not in itself a fault in their methods. And many artists now seen as post-academic, like Degas, used the camera itself as an aid to composition, and the photorealistic aspect of their work constitutes a strong element of its appeal.

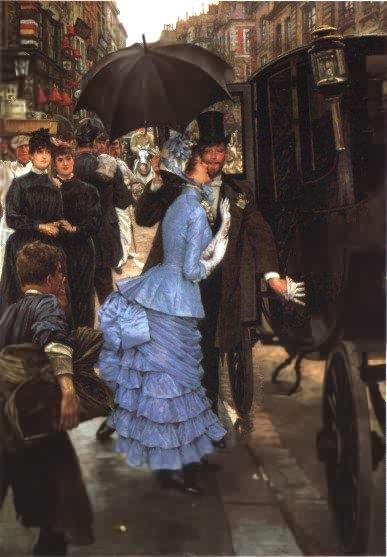

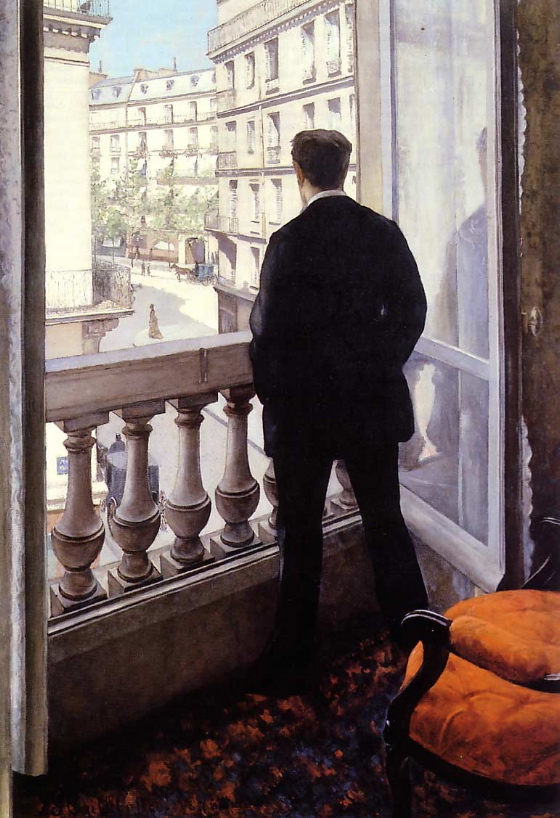

The Victorian academic painter, however, was doing something new in the

wake of the invention and widespread popularity of photography — he

was conducting a conscious dialogue with the camera. He was

incorporating a new standard of visual authority introduced by the

camera, and doing it on purpose. He knew that the experience of

viewing photographs had introduced a new relationship to visual reality

in the mind of modern man. The Victorian realist painter didn’t try to

ape the photograph, and he could exceed its resources in many areas,

but he always paid homage to its authority — and he tried to construct

a new visual aesthetic based on that authority.

His effort in that regard was the basis for the magic of Victorian

academic art, for it popularity at the time and for its enduring

appeal. Apologists for the Victorian painters often try to downplay

this aspect of the academic style, try to reconnect them to the art

that had gone before them in an unbroken tradition. But they were

radical — the photograph made them radical.

So Bouguereau wanted to show us nymphs and satyrs, wanted to show us

figures floating in mid air, but wanted us to receive the visions as

having the authority of photographs — and not just the photographs

that an actual camera of the time could make but ideal photographs,

recording the subtlest effects of light, capturing the most fleeting

nuances of gesture. He wanted to make us feel that we were

looking at an über-photograph. (Bouguereau’s fantastical work is the best

place to start in a study of the über-photographic aesthetic, because,

unlike much Victorian academic art, it takes as its subjects things

which could not be observed or staged in real life and thus could not

be photographed. It’s therefore doing something far more complex

than imitating contemporary photographic practice. If we can

locate the über-photographic aesthetic here, we can isolate it as a

purely conceptual strategy.)

And so one has the utter strangeness of Bouguereau — decidedly

corporeal figures hovering above the ground, mythological figures with

the sex appeal of naughty photographic postcards, because they seem to

represent actual naked men and women with unimpeachable authority.

Some people find Bouguereau’s nudes pornographic, and on one level they

are. Bouguereau has used his virtuosic technique to portray these

naked men and women as though they were real people recorded by a

camera, not visions transmitted through an artistic sensibility. They

have that hint of indecency, of violation, that always attaches in some

measure to photographs of naked people.

This is not something to object to — it’s what makes Bouguereau cool,

exciting, new, radical. It’s why his paintings are still alive for

people today, objects that rivet the attention, whatever judgment the

mind may be passing on them as works of art. How much more

complicated, courageous, inventive, witty was Bouguereau’s response to

the photograph than that of the modernist rebels who simply walked away from

it, turned to abstraction in defiance of the photograph’s power.

That power has not diminished over time — indeed much of our

conception of the world we live in today is determined, overdetermined,

by the photograph. Which is why on some level Bouguereau speaks to us

more deeply than the abstractionists do. Bouguereau draws us

into that same dialogue with the photograph that he himself conducted,

and in transcending its power — by seeming to carry it farther than it

can ever actually go, even in the age of Photoshop — he places it in a truer

perspective than the modernists could ever have conceived.

A distinguished museum director has observed how difficult it is to

hang Bouguereau in a modern museum — discerning a disconnect not only

between Bouguereau and 20th-Century modernism but also between

Bouguereau and the great high-art tradition his work seems to

inhabit. That is precisely because Bouguereau’s work strove for a

transcendent synthesis of painting and photography — something

no art before him could have done and no institutionally-sanctioned art

after him has chosen to do. His work is thus profoundly modern, more genuinely modern in some ways than the work of the 20th-Century abstractionists. It may be, in fact, that Bouguereau is so modern, so radical, that for some time to come he will need a room all to himself.

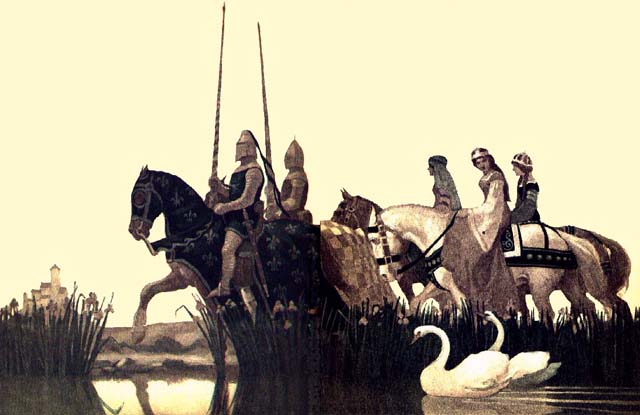

[I think the concept of the über-photograph is a useful way of distinguishing the style of the early pre-Raphaelites from the mainstream of Victorian academic art that emerged after them. Rossetti had a fundamentally painterly aesthetic with a strong bent towards the stylized and decorative, a bent developed most conspicuously in the work of William Morris. The academic painters of the second half of the 19th-Century departed from both in adopting a photo-authoritative strategy, however fanciful their subjects. Burne-Jones was a key transitional figure in this process. Though he held onto many of the painterly and decorative elements of Rossetti’s style one begins to see in his work a shift towards the photo-realistic — mainly in his strict stereometric modeling of forms and figures, which gave his paintings a sculptural quality. It was the quality of relief-sculpture, however — he rarely pursued the bold evocations of deep space that so preoccupied Alma-Tadema, Lord Leighton, Tissot and Waterhouse, to take a few examples. Their strategies with regard to spatial illusion were closely connected to the über-photographic aesthetic. By the same token, the idea of the über-photograph can be used to distinguish the project of Victorian academic painters from the sterile photo-realism of some modern painters, who are consciously evoking and aping the photograph and not trying to transcend its limitations, not trying for a new visual synthesis.]