They kidnapped the cinema, but we’ll go after it, and we’ll find it in the end, I promise you. We’ll find it. Just as sure as the turning of the earth.

Click on the image to enlarge.

Truth Escaping From the Well, 1898, an allegory in support of Dreyfus.

Escape from the Kodak Theater . . .

Men . . . with their silly quibbles!

Raincoat

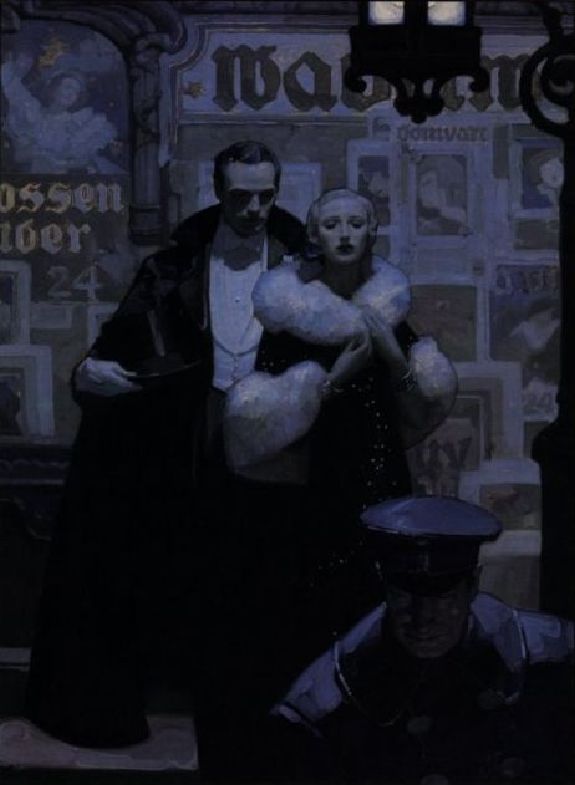

Elegant Couple, a lovely nighttime image, created as a story illustration.

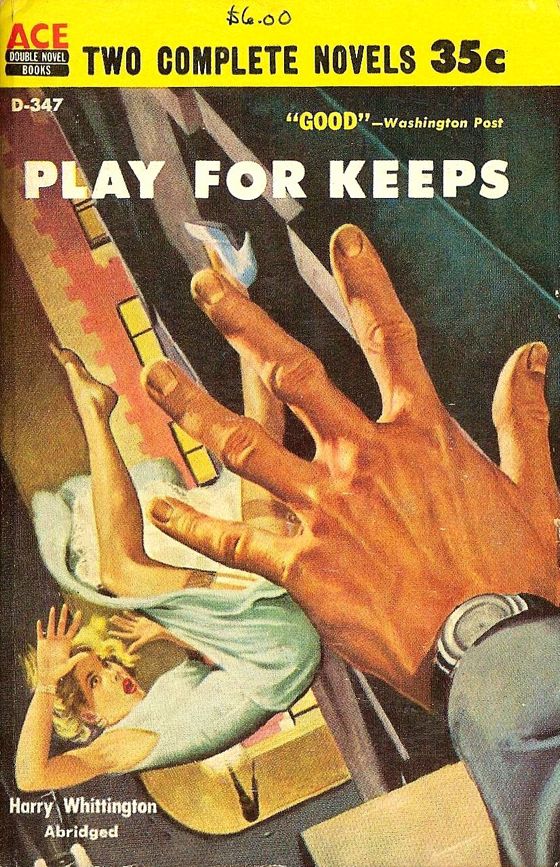

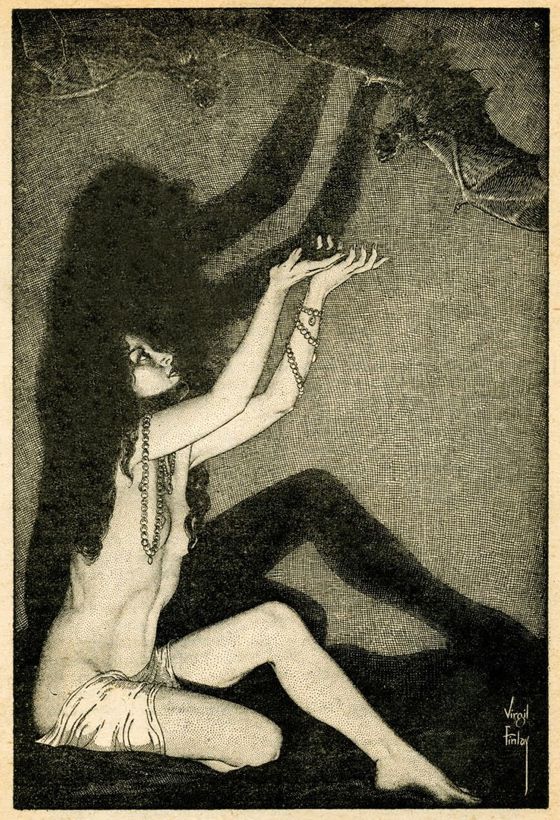

Illustration for a pulp magazine from 1952.

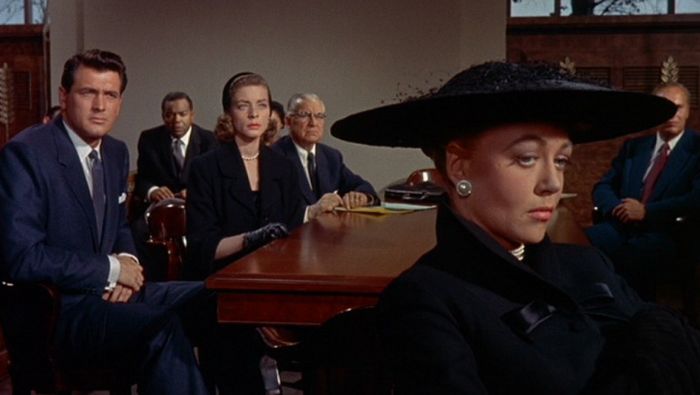

In Douglas Sirk’s movies the women think. I haven’t noticed that with

any other director. With any. Usually the women just react, do the

things women usually do, and here they actually think. That’s

something you’ve got to see. It’s wonderful to see a woman thinking.

That gives you hope. Honest.

— Rainer Werner Fassbinder

I think this is a profound insight. Most movies are made by men, and men are obsessively, if quite naturally, interested in what women think of them, and of other men. However sympathetic they may be to women, they are not much interested in what women think about other things than men, or in the thoughts of women which cannot be influenced by male behavior.

I am trying to think of exceptions to Fassbinder’s rule, and I can’t come up with much. I think we see Mattie Ross in the Coen brothers’s version of True Grit thinking.

I think we see the old and the young Rose in Titanic thinking.

I think we see Barbara Stanwyck thinking in almost every role she ever played, regardless of the lines she was reading and regardless of who was directing her.

Some other icons of female independence, like Katherine Hepburn, always seem to be reacting to men on some level, saying, in effect, “See how much I don’t need you?” — which of course is just a way of saying, “You’re going to have to come and get me.” This I think falls into the category of reacting, of doing the things women are expected to do.

Greta Garbo is an anomaly. She rarely seems to be thinking anything, even in reaction to what men do, which allows us to project thoughts into her. I wouldn’t say that we ever see her thinking, but it’s possible to imagine that we do. In a way, this is the source of her whole mystique.

I think we can see Vera Miles thinking in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence — we have to, really, because the whole truth of the film is located in her thoughts, which are never verbalized.

In odd moments here and there, in films which are dominated by a male viewpoint, we can see women thinking — in On the Waterfront, for example, we can see Eva Marie Saint thinking occasionally.

In The Palm Beach Story, Preston Sturges sometimes lets us see Claudette Colbert thinking.

It’s in musicals, curiously, in song and dance numbers, that we can most often see women thinking — Judy Garland, Eleanor Powell, Ginger Rogers, Cyd Charisse. Powell and Charisse in particular never seem overly concerned with manipulating or reacting to what men think of their sexuality — they seem to be enjoying it for its own sake, thinking about it in their own terms.

That’s about it.

Ah, Las Vegas — where the fun never stops . . .

Symphony In White No. 1

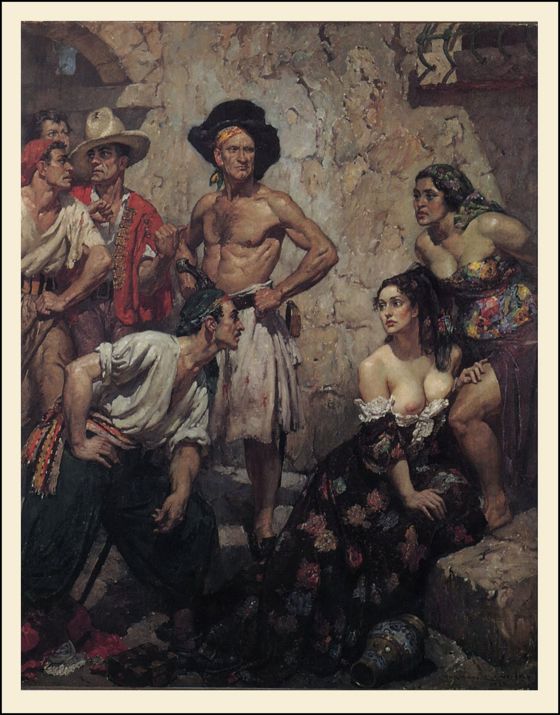

Norman Lindsay was a prolific Australian author and artist who worked in many media. He's known today mainly for his delightfully erotic line drawings featuring full-figured female nudes. Michael Powell's last film was an adaptation of Lindsay's novel The Age Of Consent, and a film about Lindsay's life, Sirens, was released in 1994.

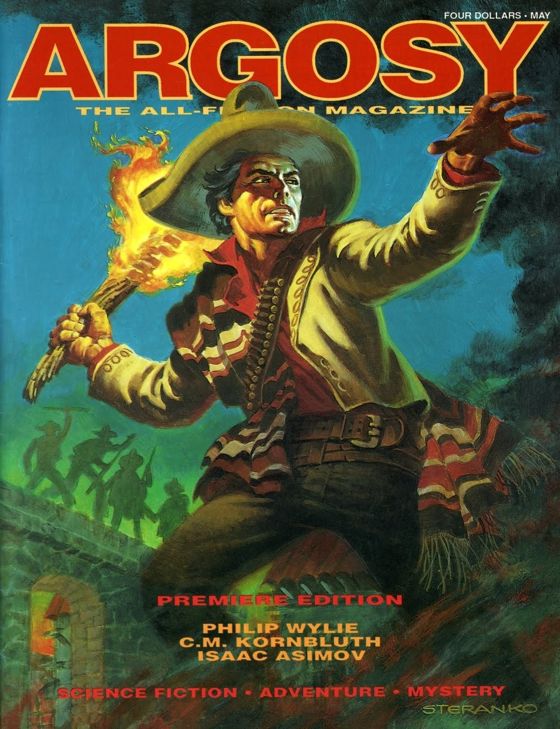

The image above, from 1938, introduces a frankly erotic element into the foursquare narrative style of N. C. Wyeth's illustrations — a slightly startling combination.