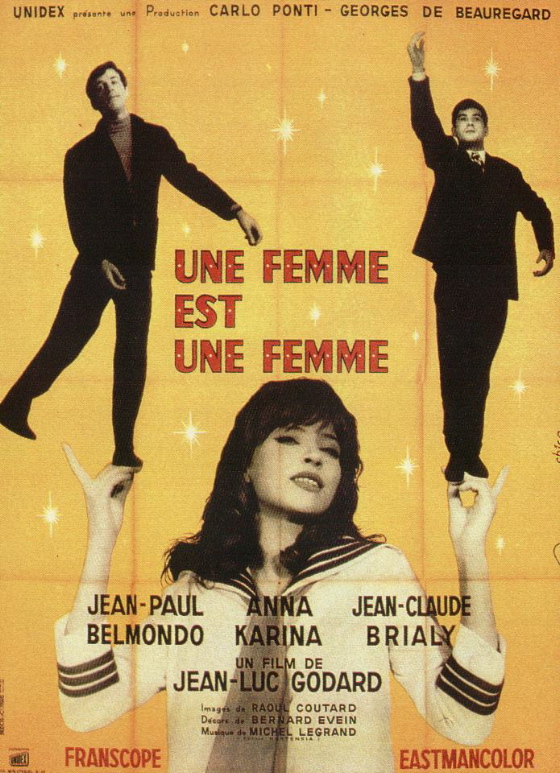

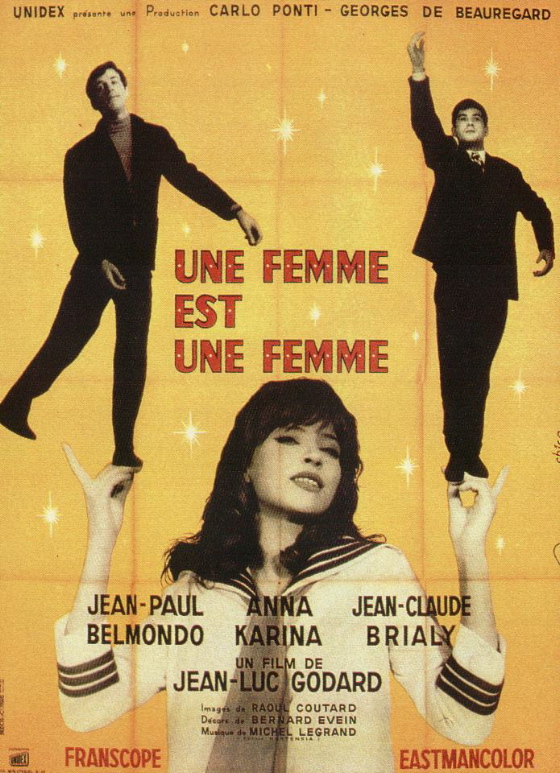

Une Femme Est Une Femme was Jean-Luc Godard’s third feature film and first in widescreen and color. It’s a work of narrow but intriguing ambitions. Godard said that it was a film about the tragic fact that life is not a Hollywood musical. It evokes the surreal effects and moods of a Hollywood musical without the virtuosity of dance and vocal performance Hollywood could provide, resulting in an unsettled and unsettling tone.

On one level the film is an attempt to imagine Anna Karina, Godard’s muse at the time, as a creature of the mythic territory of the great MGM musicals. Godard even has his actress, in character, say that she wants to star in a musical with Cyd Charisse and Gene Kelly.

Karina has the charm and beauty and screen presence for this but not the dancing and singing chops. So the silly romantic comedy plot, and the somewhat dimwitted bourgeois characters caught up in it, keep dragging the film relentlessly back into the mundane.

This can be read in several different ways — as a critique of bourgeois culture, enchanted and misled by an illusory screen world it cannot ever be a real part of . . . as a hopeless fantasy by Godard about his lover actually inhabiting such a world, or about himself actually creating one cinematically. One suspects that Godard was in part just covering himself with the notion of the film as a critique — that his own fantasies played as much a part in the film’s creation as his theoretical deconstruction of the musical form.

This dynamic haunts all of Godard’s cinema — he came to hate the part of himself that was enchanted and misled by Hollywood, but it remained a part of him. For Godard, celebrating and reviling the Hollywood cinema were two sides of the same coin, reflecting a singular passion for and contentious dialogue with American films.

By deconstructing the odd conventions of American musicals, pushing them into a new mode of self-consciousness, Godard teaches us a lot about how these Hollywood films seduce us, move us half-consciously into a cinematic dream.

Karina’s petulant, amoral femme is not a terribly appealing character, but when she sings, however amateurishly, in one of the film’s fractured production numbers, when she smiles sweetly at the camera, to let us know she’s in on the joke, she wins us over — transports us out of the banal narrative and dialogue into a world where wonders might be possible. She can’t keep us there, or transcend the mundane world her character inhabits through virtuoso dancing or singing, but she shows us how the door into transcendence is opened.

Although this film has a fairly conventional story, and a lighthearted tone, it is in some ways the most severely theoretical of Godard’s early films — or perhaps one should say it is best appreciated on that level today. As a “documentary” about Karina behaving in front of the camera the film bears too much evidence of Godard’s self-indulgent obsession with the woman herself. The film’s whimsy hasn’t aged at all well.

There are no moments of genuine movie musical magic — such as can be found in the Madison dance in Bande À Part, for example, which, modest as it may be by MGM standards, was achieved the old-fashioned way, by a month of daily rehearsals before shooting.

As a meditation on, as a hopeless love letter to American musicals, the film rewards close investigation, however, and is a fascinating case study in Godard’s problematic relationship with American cinema in general, which ravished and horrified him in equal measure. American cinema is the real femme of the film’s title, the real subject of its final punning lines.

“Tu es infâme,” says the Brialy character to his lover — you are despicable. “Non,” says Karina’s character, with a last irresistible wink and smile, “je suis une femme” — I’m just a woman. From somewhere in between these two views, of women and of Hollywood, all the contradictions of Godard’s own practice of cinema arise.